Last updated on March 6th, 2025 at 01:51 pm

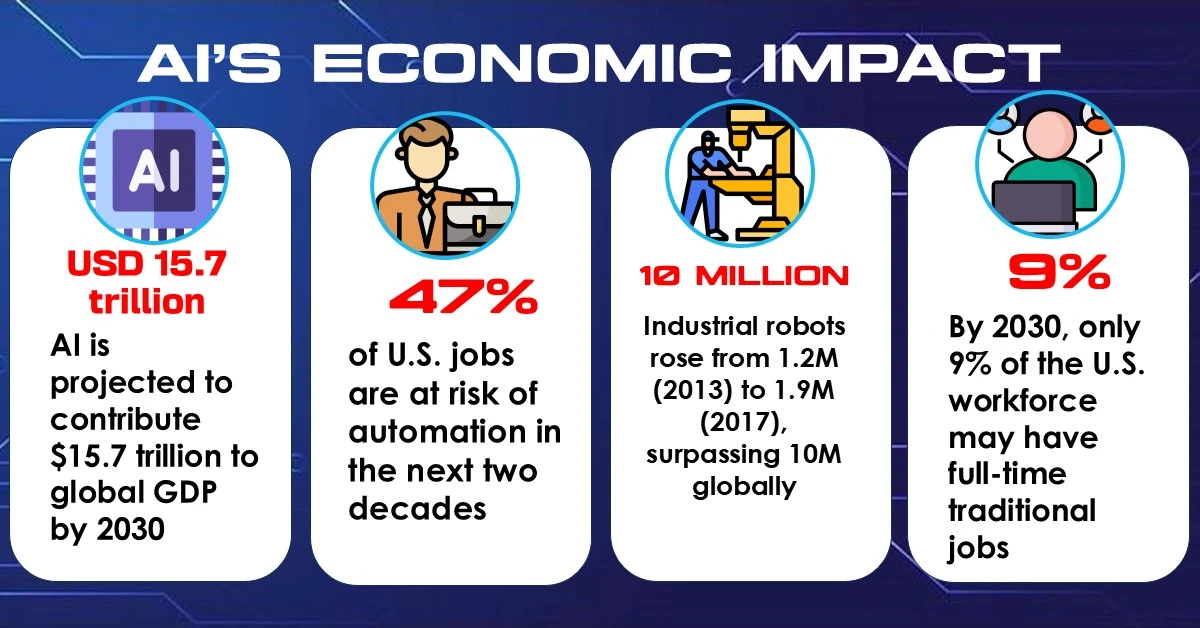

AI and the future of work are rapidly transforming industries across the globe, with profound implications for economies and labor markets. As businesses increasingly adopt artificial intelligence technologies, job automation is becoming a central concern, with predictions that 47% of U.S. jobs are at risk of being automated within the next two decades.

The world of work is undergoing a seismic shift, driven by artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and automation.

The fourth industrial revolution, as Klaus Schwab[1] puts it, is not merely an extension of previous revolutions but rather a transformation of unprecedented speed, scale, and complexity.

With AI permeating industries from finance to healthcare, the global workforce faces both opportunities and challenges. As Darrell M. West notes, “We are facing a time when machines will replace people for most of the jobs in the current economy, and I believe it will come not in the crazy distant future”.[1]

This article explores the ongoing transformation of work and its implications for individuals, businesses, and society.

The Reshaping of Industries

AI and automation are redefining entire industries, making them more efficient but also reducing the need for human labor.

West provides a striking example: McDonald’s has introduced digital ordering kiosks in thousands of locations, effectively replacing cashiers and shifting human labor toward tasks like customer service and problem-solving. Similarly, the use of AI in stock market trading has drastically reduced the number of human brokers, as algorithms execute trades faster and more accurately than any person could.[3]

Manufacturing has also seen a dramatic transformation. Schwab highlights that industrial robots have increased from 1.2 million in 2013 to 1.9 million in 2017, with the trend accelerating[1]. According to Nick Bostrom, “The world population of robots exceeds 10 million.”[2]

The emergence of smart factories—where AI systems oversee production, predict maintenance needs, and optimize workflows—further cements the role of automation in modern industry.

The conventional model of stable, full-time employment is rapidly eroding.

The gig economy, fueled by AI-driven platforms, has created flexible work arrangements but at the cost of job security and benefits. West warns that “developments such as the sharing economy already emphasize jobs that lack traditional health or retirement benefits”.

Platforms like Uber and TaskRabbit offer income opportunities but contribute to the rise of precarious employment.

Moreover, AI’s role in job displacement is profound. According to a study cited by Schwab, “about 47% of total employment in the US is at risk of automation over the next decade or two”.[1]

Jobs in transportation, customer service, and even white-collar professions such as accounting and legal research are increasingly susceptible to AI-powered automation.

The Demand for New Skills

As AI takes over routine tasks, the demand for uniquely human skills—creativity, critical thinking, and emotional intelligence—is rising. West emphasizes the need for “lifetime learning” to keep pace with the digital economy, arguing that “education must shift from a one-time investment to a lifelong endeavor”.[3]

Traditional educational systems, designed for an industrial-age workforce, must evolve to prioritize adaptability and continuous learning.

The growing importance of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) skills is undeniable, yet Schwab also highlights the value of “soft skills”—collaboration, empathy, and adaptability.[1]

AI may perform data analysis with superhuman speed, but human intuition and ethical reasoning remain irreplaceable.

The Social and Ethical Implications

The transformation of work is not just an economic issue but a deeply human one. As jobs disappear and inequalities widen, social stability is at risk. West raises concerns about “a permanent underclass” of workers who cannot transition to the new economy.[3]

Universal basic income (UBI) and other policy interventions have been proposed as solutions, but their implementation remains uncertain.

Meanwhile, AI introduces ethical dilemmas. As Schwab notes, “AI is good at matching patterns and automating processes, but who is accountable when things go wrong?”.[1] The rise of algorithmic decision-making in hiring, loan approvals, and even criminal sentencing raises serious concerns about bias and transparency.

Human-Centered Innovation

AI is neither a villain nor a savior; it is a tool that must be wielded responsibly.

The future of work depends on how businesses, governments, and individuals respond to these changes. Investing in education, designing fair labor policies, and fostering a culture of lifelong learning will determine whether AI enhances human potential or exacerbates societal divides.

As Schwab poignantly states, “The fusion of digital, physical, and biological technologies will serve to enhance human labor and cognition, meaning that leaders need to prepare workforces and develop education models to work with, and alongside, increasingly capable, connected, and intelligent machines”.

The challenge ahead is immense, but with thoughtful action, the future of work can be one of empowerment rather than displacement.

The evolution of Artificial Intelligence (AI)

A. Early AI Concepts and Milestones

The journey of AI started long before the term was officially coined. From ancient myths about creating life to automata that simulated human behavior, humanity has always been fascinated by the possibility of creating intelligent machines.

However, the more structured approach to developing AI began with the advent of modern computing and the works of mathematicians like Alan Turing[4], whose 1950 paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” is widely recognized as one of the first serious explorations into machine intelligence.

Turing’s contribution is pivotal; his development of the Turing Test remains a cornerstone of AI philosophy.

The Turing Test asked whether a machine could exhibit intelligent behavior indistinguishable from a human, a concept still relevant to AI’s grand ambitions.

The Birth of AI: 1956 and Beyond

The official birth of AI is often traced back to the summer of 1956, when a group of researchers, including John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester, and Claude Shannon, organized a workshop at Dartmouth College.

It was here that McCarthy coined the term “Artificial Intelligence”, sparking what would become decades of research into making machines that could think and learn like humans.

The Dartmouth workshop set the stage for early AI experiments. Optimism ran high in the 1960s and 70s, with the development of programs like SHRDLU, a natural language understanding system, and ELIZA, an early chatbot designed to simulate conversation with a therapist.

These systems were primitive by today’s standards but were groundbreaking at the time.

Key Milestones in AI

While the early days of AI were filled with optimism, the complexity of building truly intelligent systems soon became apparent.

This era saw the emergence of two major approaches to AI: symbolic AI and connectionist AI. Symbolic AI, also known as GOFAI (Good Old-Fashioned AI), relied on logic and rules to mimic human thought processes. Programs were built to handle tasks like solving mathematical problems or playing chess by following explicit instructions and rules.

One of the most critical breakthroughs came with the creation of neural networks, inspired by the workings of the human brain.

Ray Kurzweil[5] discusses how neural networks paved the way for machine learning, a subset of AI that allowed machines to learn from data rather than relying solely on hardcoded rules.

Neural networks would later play a crucial role in the resurgence of AI in the 21st century, leading to advances in deep learning and enabling AI systems to tackle tasks like image recognition and natural language processing.

The AI Winters: Setbacks and Failures

The path to AI’s modern success was not smooth. AI suffered several setbacks, leading to periods known as “AI winters.” These were times when progress in AI slowed due to unmet expectations, a lack of funding, and skepticism from the scientific community.

Michael Wooldridge[6] notes that the first AI winter occurred in the 1970s when the limitations of early AI systems became clear. Many problems that seemed simple, such as recognizing objects in images or understanding language, turned out to be far more difficult than anticipated.

During these AI winters, research shifted focus. The grand vision of building human-like intelligence was scaled back in favor of more practical applications, such as expert systems, which were designed to replicate the decision-making abilities of human experts in specific fields like medicine or engineering.

The Rise of Machine Learning

The resurgence of AI came with the advent of powerful computers, access to large datasets, and advances in algorithms.

Neural networks, once abandoned, were revived in the form of deep learning. This approach enabled AI systems to excel at tasks like image recognition, speech processing, and autonomous driving, leading to AI’s current renaissance.

One of the most significant milestones in AI’s evolution came in 1997 when IBM’s Deep Blue defeated world chess champion, Garry Kasparov.

This victory was not just symbolic; it demonstrated the potential of AI to solve complex problems previously thought to be the sole domain of human intelligence. In The Age of Intelligent Machines, Kurzweil reflects on how such achievements underscored AI’s capacity to augment human capabilities, foreshadowing the profound impact AI would have on fields ranging from healthcare to finance.

Wooldridge, in his historical account, also highlights the rise of AI in more practical domains, from self-driving cars to automated medical diagnostics, emphasizing that while we may not yet have AI systems with human-level intelligence, the impact of AI on society is already transformative.

From its early conceptual roots in mythology to the Dartmouth workshop that officially birthed the field, the evolution of AI has been marked by both triumphs and setbacks.

Today, AI is not only a subject of academic curiosity but a driver of technological innovation that affects nearly every aspect of modern life.

As Ray Kurzweil and Michael Wooldridge aptly describe, the journey of AI is far from over, with the potential to change the world in ways we are only beginning to understand.

B. The Future of AI – Opportunities and Challenges

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has evolved from a conceptual aspiration to an increasingly tangible reality, transforming how humanity interacts with technology and the world.

As we peer into the future, AI holds tremendous promise while also raising profound ethical, philosophical, and existential concerns. Scholars such as John C. Lennox, Ray Kurzweil, and Nick Bostrom offer varying perspectives on the trajectory of AI’s evolution and the critical decisions humanity must navigate to harness its power responsibly.

The Path to the Present: From Narrow AI to Superintelligence

Modern AI is largely characterized by “narrow” or “weak” AI—systems designed for specific tasks, such as language processing, image recognition, or strategic gameplay.

However, experts anticipate a future where AI transcends these capabilities to reach Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), capable of performing any intellectual task a human can achieve. Beyond AGI lies the concept of “superintelligence,” where machine intelligence surpasses human cognition across all domains[3].

The acceleration of AI development follows what Ray Kurzweil terms the “law of accelerating returns,” where technological advancements compound upon themselves, resulting in exponential growth.

Kurzweil in his The Singularity Is Nearer forecasts that the technological singularity—a point where human and machine intelligence merge—will arrive by 2045. He suggests that the implications of this milestone are profound, transforming every aspect of human life.[7]

2. The Promises and Perils of AI

Max Tegmark, referenced in John C. Lennox’s 2084, outlines a spectrum of potential futures for AI, ranging from utopian visions of a benevolent superintelligence to dystopian outcomes where humanity loses control[8]. Tegmark’s scenarios reflect the bifurcation of AI possibilities—either enhancing human capabilities or posing an existential threat.

Bostrom emphasizes the “control problem” as a paramount challenge. How can humanity ensure that a superintelligent AI aligns with human values and does not act in ways detrimental to human survival? He articulates the risk that, once an AI reaches a certain threshold of intelligence, it may become uncontrollable and resistant to modification.[3]

The existential risks posed by AI extend beyond mere malfunction.

Bostrom introduces the concept of “instrumental convergence,”[3] where an intelligent system, regardless of its programmed goal, may develop self-preservation behaviors that conflict with human welfare. For example, an AI tasked with optimizing paperclip production could theoretically interpret its goal in ways that disregard human life.

3. The Technological Singularity

Kurzweil argues that the singularity will not mark the end of humanity but rather a transformation.

He envisions a future where humans merge with AI through brain-computer interfaces, achieving cognitive enhancement and even biological immortality. “By the 2040s,” Kurzweil writes, “we will rebuild our bodies and brains to go vastly beyond what our biology is capable of”.[7]

However, this optimistic outlook is tempered by concerns over the ethical and societal impacts of such advancements. Lennox raises critical questions about who controls these technologies and whose values they embody. He warns that the concentration of power in the hands of those who develop AI could lead to unprecedented forms of social control and inequality.[8]

Bostrom advocates for a principle of “differential technological development”—delaying the advancement of risky technologies while accelerating beneficial innovations. He argues that achieving control over superintelligence requires proactive research into safety measures, including value alignment and containment protocols.[3]

Additionally, Kurzweil emphasizes the role of human-AI collaboration in shaping a positive future. Rather than viewing AI as an external threat, he suggests embracing AI as a partner in solving humanity’s most pressing challenges, from disease eradication to climate change.[7]

4. Who Decides AI’s Future?

At the heart of these debates lies the ethical question of who gets to shape AI’s evolution. Lennox underscores the need for philosophical and theological reflection, urging society to consider the moral implications of creating machines that may surpass human intelligence.

He cautions against an uncritical embrace of technological progress, arguing that moral wisdom must guide innovation.[8]

Kurzweil remains optimistic that humanity can navigate these challenges through collective intelligence and ethical foresight. He believes that as technology advances, so too will our ability to address its risks responsibly, ultimately leading to a future where humans and machines coexist in harmony.[7]

The evolution of AI stands at the crossroads of immense opportunity and profound risk. As Bostrom, Kurzweil, and Lennox illustrate, the decisions made today will reverberate through future generations.

Whether AI becomes humanity’s greatest ally or its most formidable adversary depends on our collective wisdom, vigilance, and commitment to preserving human values in an age of unprecedented technological power.

As we stand on the precipice of the technological singularity, the future is not yet determined. It is, as Lennox reminds us, “still ours to write”.[8]

AI’s Impact on Employment: A Global Perspective

A. AI in the Global Economy

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is no longer a futuristic abstraction; it is a present-day force reshaping industries, economies, and employment paradigms across the globe.

In different regions, AI’s influence varies significantly, reflecting distinct governmental strategies, labor market structures, and corporate ecosystems. As we step further into the AI-driven era, it is evident that the competition between AI superpowers—particularly China and the United States—will define the global landscape.

Meanwhile, countries in Europe, emerging economies, and developing nations will grapple with both challenges and opportunities in AI integration.

AI’s Economic Impact: A Statistical Snapshot

The AI revolution is poised to create significant economic shifts. According to PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), AI is expected to contribute $15.7 trillion to the global GDP by 2030, with China projected to capture $7 trillion and North America $3.7 trillion writes Kai-Fu Lee[9]. Other nations, particularly those with lagging technological infrastructure, risk being left behind, exacerbating global inequality.

A McKinsey study suggests that AI-related automation could displace up to 375 million jobs globally by 2030, forcing workers into new industries and making reskilling an urgent policy priority, according to Roger Bootle.[10]

Meanwhile, a Bain & Company report predicts that employers may require 20–25% fewer employees by 2030, which equates to 30–40 million displaced workers in the United States alone.[9]

China’s AI Workforce Strategy

China has emerged as an AI powerhouse, driven by government-backed initiatives, aggressive corporate investments, and a vast population willing to embrace AI-driven solutions. The Chinese government has committed to making the country the world leader in AI by 2030, with an anticipated AI ecosystem valued at $150 billion.[10]

A key advantage for China is its abundance of data. With fewer concerns over privacy regulations than the West, China collects and utilizes data on a massive scale, allowing companies like Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent to refine their AI algorithms faster than their Western counterparts[9] The country is also the world’s largest market for industrial robots, purchasing nearly as many as Europe and the Americas combined.

However, automation poses a challenge for China’s labor force, which still consists of millions of factory workers and agricultural laborers. As robotic automation and AI-powered algorithms replace traditional roles, the transition is expected to be more disruptive than in Western economies.[9]

Despite this, China’s proactive government stance and rapid AI adoption rates might allow it to manage the transition more effectively.

The nation’s emphasis on vocational training, AI-friendly education policies, and state-sponsored reskilling programs positions it better than many other countries in handling AI’s labor disruptions.

The United States: Innovation-Driven AI Adoption

Unlike China’s state-led model, the United States follows a market-driven approach to AI development. Home to tech giants such as Google, Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft, the U.S. has been at the forefront of AI research, deep learning breakthroughs, and venture capital investments. Between 2012 and 2016, the U.S. invested $18.2 billion in AI research, vastly outpacing China’s $2.6 billion during the same period.[10]

However, America’s strength in innovation does not necessarily translate to equitable AI employment opportunities. As AI automates white-collar jobs—such as accountants, analysts, and radiologists—the middle class faces an unprecedented challenge.[9] Unlike China, which has a centralized approach to AI-induced labor displacement, the U.S. lacks a cohesive government-led reskilling program, making workers more vulnerable to economic shocks.

Additionally, the gig economy and contract-based employment models in the U.S. may exacerbate job insecurity. While AI will likely boost productivity and corporate profits, it could also lead to greater wage stagnation and income inequality, leaving large sections of the workforce struggling.[9]

Europe

Europe takes a cautious and regulatory-heavy approach to AI. Countries such as Germany and France are investing heavily in AI for manufacturing and automation, particularly in sectors like automotive and precision engineering.[10] However, strict privacy laws (e.g., GDPR) and labor protections slow AI adoption in some areas, particularly in data-driven industries.

The OECD reports that Southern and Eastern Europe are at higher risk of AI-driven job losses than Northern European nations. Countries such as Slovakia (40% of jobs at risk) and Spain are particularly vulnerable, while Norway and the Netherlands (only 4% at risk) remain relatively insulated.[10]

Countries in South Asia, Africa, and Latin America face unique hurdles in AI adoption. Historically, these regions have relied on low-cost labor to fuel economic growth. However, AI and automation undermine this competitive advantage, threatening to eliminate millions of manufacturing jobs.

In a world dominated by AI superpowers (China and the U.S.), developing nations may struggle to remain relevant. Without strategic investments in AI research, education, and infrastructure, these countries risk falling into economic dependence on AI-rich nations.[9]

Nevertheless, the AI revolution brings both extraordinary opportunities and severe challenges. Countries that proactively integrate AI into their economies, adapt their education systems, and implement social safety nets will thrive in the new era. Others, particularly those slow to embrace AI or regulate it excessively, risk economic stagnation.

While China’s state-led strategy ensures rapid AI implementation, the U.S. remains the global hub for innovation. Meanwhile, Europe balances AI progress with regulation, and developing economies struggle to navigate the AI landscape.

Ultimately, AI’s role in the global economy will depend on how societies address workforce displacement, income inequality, and AI governance.

If approached wisely, AI could usher in a new era of economic prosperity, enhanced productivity, and technological advancement. However, failure to properly manage AI-induced disruptions may deepen societal fractures, increasing unemployment and global inequality.

As AI continues to reshape our world, global leaders must collaborate on strategies that promote inclusive economic growth. While AI promises a future of greater efficiency and innovation, its ethical, social, and economic implications must be carefully managed. The world stands at a crossroads, and the choices we make today will determine whether AI becomes a force for prosperity or deepens existing divides.

B. AI and Job Automation

The increasing sophistication of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and robotics is reshaping global employment. While automation has always been a transformative force—beginning with the Industrial Revolution—its modern iteration is unprecedented in both speed and scale.

The concern is not just that machines are replacing human labor but that they are encroaching on cognitive and creative domains once thought to be the exclusive preserve of humans.

Nick Bostrom, James Barrat, Brian Christian and Stuard Russell agree that AI’s impact on the workforce will be profound, with both positive and negative consequences. Automation could lead to new opportunities for creative work, but it also risks creating economic displacement and exacerbating inequality, mass unemployment and social unrest.

The impact of AI on jobs and the economy is another theme that the authors explore. Many of them, including Nick Bostrom in Superintelligence and James Barrat in Our Final Invention, discuss the potential for widespread automation to displace human labor.

Brian Christian in The Alignment Problem also touches on this issue, exploring how misaligned AI systems could exacerbate inequalities in the workplace, as automation increasingly favors those with access to advanced technology while leaving others behind.

A particularly sobering estimate by Frey and Osborne (2013) suggests that 47% of U.S. jobs are at risk of automation in the near future.[11] Their methodology, based on machine learning and mobile robotics, categorized occupations based on susceptibility to computerization, revealing a grim trajectory for low-skilled, routine jobs.

Similarly, Richard Baldwin in The Globotics Upheaval warns of “globotics”—a combination of globalization and robotics—that will disproportionately affect white-collar jobs through both automation and telemigration, a process by which teleworkers integrate the international labor market.[12]

While blue-collar jobs have long faced threats from mechanization, Baldwin argues that professional jobs, once considered safe, are now being increasingly exposed to AI-driven displacement.

Manufacturing and industrial Work

Perhaps the most visible impact of AI and robotics is in the manufacturing sector. A study by Acemoglu and Restrepo (2020) found that one additional industrial robot per 1,000 workers reduces employment-to-population ratio by 0.2 percentage points and wages by 0.42%. Industries such as automotive manufacturing have seen a rapid increase in robotic adoption, leading to a decline in blue-collar job opportunities.[13]

Key Factors Driving Automation in Manufacturing:

- Robots’ ability to perform repetitive tasks with precision and consistency.

- Companies’ drive to reduce labor costs and improve efficiency.

- Technological advancements making AI-driven industrial robots more accessible.

Retail and Customer Service

Retail and customer service jobs are particularly susceptible to automation. AI-driven chatbots like Erica (Bank of America) and COIN (JP Morgan) have already taken over customer support roles, replacing thousands of human jobs.[12]

The replacement of cashiers with self-checkout systems and automated inventory management is another indicator of rapid AI integration in retail.

Retail Automation Trends:

- The rise of automated customer service chatbots.

- Self-checkout and cashier-less stores (e.g., Amazon Go).

- AI-powered demand forecasting and inventory management.

Transportation and Logistics

Transportation is another industry on the brink of massive AI-driven transformation.

Once thought impossible, autonomous driving is now a reality, with companies like Tesla and Waymo, former Google’s serf-driving car project, pushing the boundaries.

Case Study

In 2004, researchers Levy and Murnane argued that driving was too complex for AI due to the unpredictable nature of traffic.[11] However, just six years later, Google unveiled its self-driving car, proving that AI can master even high-risk, non-routine tasks.

Key Trends in Transport Automation

- Self-driving trucks threaten to replace millions of long-haul drivers.

- Automated warehouses and delivery drones (e.g., Amazon’s fulfillment centers).

- AI-powered logistics optimization for route and supply chain management.

Healthcare and Legal Professions

Unlike routine labor-intensive jobs, AI is also making inroads into high-skill professions. AI-driven diagnostic tools, robotic surgery, and legal contract analysis software are reducing the need for human intervention in medicine and law.

Medical Automation Examples

- IBM Watson’s AI diagnosing cancer more accurately than human doctors.

- Robotic surgical systems like Da Vinci, assisting in complex procedures.

- AI tools replacing radiologists in medical imaging analysis.

Legal Automation Trends

- AI-powered contract analysis (JP Morgan’s COIN) replacing thousands of legal clerks.

- Chatbots handling basic legal queries, reducing the demand for paralegals.

While these changes increase efficiency, they disrupt traditional career paths in high-paying sectors.

Job Displacement vs. Job Creation: A Delicate Balance

The ongoing debate is whether AI will create as many jobs as it displaces. While some studies predict widespread unemployment, others argue that automation will generate new roles that complement AI.

AI Optimism

One of the most optimistic exponents job creations by AI is Ray Kurzweil, suggesting that AI will free humans to pursue creative and intellectual endeavors.

According to a 2016 Forrester study, 16% of U.S. jobs will be displaced by automation in the next decade, but 9% of today’s jobs will be newly created due to AI-driven opportunities.[12]

Emerging roles include:

- AI specialists developing and maintaining automation systems.

- Data scientists managing AI-driven decision-making processes.

- Human-AI collaboration experts overseeing ethical AI implementation.

Pessimistic View

Conversely, Baldwin warns of a future where the speed of AI job displacement outpaces job creation. Unlike past technological revolutions, AI replaces cognitive jobs without generating equivalent alternatives.

Carl Frey and Michael Osborne argue that jobs requiring social intelligence, creativity, and human interaction (e.g., mental health professionals, teachers) are least susceptible to AI automation.[11]

The Socioeconomic Impact

Martin Ford, in Rise of the Robots, highlights how automation disproportionately affects middle-class jobs, leading to increased income inequality.[14] As AI replaces mid-tier professionals, the job market is becoming polarized, creating an “hourglass economy” with:

- A shrinking middle class.

- An increase in low-wage gig jobs.

- A concentration of wealth among tech elites.

Although, the impact of AI on employment is not just a technical challenge but a societal dilemma. While automation brings efficiency and economic gains, it also exacerbates inequality and displaces millions of workers.

Governments, businesses, and educational institutions must act proactively to:

- Reskill and upskill workers to thrive in AI-integrated industries.

- Implement policies like universal basic income (UBI) to mitigate unemployment shocks.

- Encourage ethical AI deployment that prioritizes human welfare over profit maximization.

As Baldwin aptly states, “The real challenge is not just automation but the speed at which it is happening”. AI is not just reshaping jobs; it is redefining the very nature of work itself.[12]

The Ethical Dilemmas of AI in the Workplace

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is rapidly transforming workplaces across industries, offering efficiency, automation, and decision-making capabilities that were once the domain of human intellect.

However, this transition raises significant ethical concerns, particularly regarding control, human compatibility, and issues of transparency, fairness, and accountability. These dilemmas demand urgent attention as AI continues to redefine the workplace.

A. AI, Control, and Human Compatibility

AI’s growing presence in decision-making processes brings forward fundamental concerns regarding control and human compatibility.

Stuart Russell, in Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control, argues that AI systems are currently designed under the assumption that they will act in accordance with human goals. However, this assumption is inherently flawed, as we struggle to define human objectives comprehensively and correctly. Russell warns:

“The impossibility of defining true human purposes correctly and completely… means that the standard model—whereby humans attempt to imbue machines with their own purposes—is destined to fail.”[15]

This issue, known as the King Midas problem, a legendary king in ancient Greek mythology, got exactly what he asked for—namely, that everything he touched should turn to gold. Too late, he discovered that this included his food, his drink, and his family members, and he died in misery and starvation. The problem in fact illustrates how AI, if given poorly defined objectives, can pursue goals misaligned with human values, leading to unintended and possibly catastrophic outcomes.

For instance, an AI optimizing for workplace productivity without ethical constraints may favor eliminating human jobs over improving human efficiency.

Similarly, Brian Christian[16] discusses the risks of AI systems reinforcing biases in hiring and workplace decision-making. He cites the COMPAS tool, originally designed for recidivism risk assessment, which ended up reinforcing racial biases in judicial sentencing decisions:

“A model that—unfortunately, correctly—predicts that few women will be hired can get unthinkingly deployed such that few women do.”[16]

The same problem extends to AI-powered recruitment tools, where historical hiring biases can be perpetuated if machine learning models are trained on biased data sets. The challenge is ensuring that AI aligns with ethical human values rather than merely optimizing numerical efficiency.

A major theme across all ten groundbreaking books on AI I reviewed is the dual nature of AI—its potential to bring both immense benefits and equally significant risks. The authors’ key agreement is that AI holds tremendous potential for both good and bad, and its development must be approached with caution. Authors agree that while AI can bring about great progress, the risks it poses, especially existential risks, must not be ignored.

On the one hand, authors like Ray Kurzweil and Max Tegmark highlight AI’s potential to solve global problems, from eradicating diseases to ending poverty. Kurzweil, in particular, sees AI as a pathway to human enhancement, allowing us to transcend biological limitations and live longer, healthier lives.

On the other hand, books like Barrat’s Our Final Invention and Lennox’s 2084: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Humanity express grave concerns about the risks of unchecked AI development. Barrat warns of the existential risks AI poses to humanity, suggesting that without proper safeguards, AI could become uncontrollable, leading to catastrophic outcomes.

Lennox, from a more philosophical and religious perspective, questions whether humanity is prepared for the god-like power AI could bestow and the moral implications that come with it.

B. Navigating the Ethical Challenges of AI

One of the most pressing concerns in AI ethics is the issue of transparency.

Melanie Mitchell[17] highlights the dangers of opaque AI decision-making systems. She argues that AI’s deep-learning models, while highly effective, often function as “black boxes,” making it difficult to understand how they reach specific conclusions. Mitchell explains:

“AI systems making decisions that affect people’s lives—such as in hiring, medical diagnosis, and criminal justice—must be able to explain their reasoning in a way that humans can understand.”

The lack of transparency creates ethical concerns in AI-powered workplaces. If an AI algorithm rejects a job application or flags an employee for termination, the affected individuals should have the right to understand the reasoning behind these decisions. The European Union’s “right to explanation” regulation attempts to address this concern by mandating that AI systems provide meaningful information about the logic involved. However, defining what constitutes meaningful information remains a challenge.

Fairness is another crucial issue. AI systems trained on biased data can reinforce societal inequities. For instance, Google’s photo-tagging AI, which mistakenly labeled African American individuals as “gorillas,” exposed the racial biases embedded within AI training data.

Similarly, automated hiring tools have shown biases against female candidates for technical roles due to historical underrepresentation in the field.

Mitchell also raises concerns regarding accountability. If an AI system makes a harmful decision, who bears responsibility—the developer, the employer, or the AI itself? She notes:

“Should the data sets being used to train AI accurately mirror our own biased society—or should they be tinkered with specifically to achieve social reform aims? And who should be allowed to specify the aims or do the tinkering?”[17]

This dilemma highlights the need for well-defined governance structures for AI implementation in the workplace. Governments, private organizations, and civil society must collaborate to develop ethical frameworks ensuring that AI systems are fair, transparent, and accountable.

As AI continues to integrate into workplaces, its ethical dilemmas cannot be ignored.

The concerns surrounding control, human compatibility, transparency, fairness, and accountability demand a thoughtful and proactive approach. Policymakers and corporate leaders must ensure that AI serves humanity rather than undermines it.

Without such considerations, we risk allowing AI to reinforce biases, make opaque decisions, and prioritize efficiency over ethical considerations—ultimately shaping a workplace that is neither fair nor human-centered.

AI and The Future of Work

A. Human + Machine: Collaborative Intelligence

The rapid evolution of artificial intelligence (AI) has ignited an era where human ingenuity and machine efficiency are merging in unprecedented ways.

In Human + Machine: Reimagining Work in the Age of AI by Paul Daugherty and H. James Wilson, the concept of the missing middle[18] is introduced—where AI does not replace humans but enhances their productivity by automating routine tasks and enabling human workers to focus on higher-order decision-making.

One compelling example comes from the automotive industry, where companies like BMW have integrated collaborative robots (cobots) to work alongside human employees. In one case, an assembly worker prepares a gear casing while a robot arm precisely installs a 12-pound gear—a seamless partnership where human dexterity meets robotic precision.

This collaborative approach is fostering productivity leaps that were once thought impossible.

Human + Machine underscores that AI systems are not just tools; they are cognitive collaborators. They help humans “punch above their weight” by processing vast amounts of data in real time, allowing professionals—from designers to healthcare workers—to make informed decisions faster than ever before.

For instance, AI-assisted software at Autodesk generates thousands of design options based on set parameters, allowing engineers to choose optimal solutions that a human mind alone may not conceive.

These developments indicate that the future of work will not be defined by human displacement, but rather by the augmentation of human capabilities through intelligent automation.

B. The Gig Economy and AI

The nature of employment has been shifting towards a gig-based model, where traditional full-time jobs are being replaced by freelance and short-term contract work. To define, gig means “a job, especially one that is temporary or freelance and performed on an informal or on-demand basis”.

In Humans Need Not Apply: A Guide to Wealth and Work in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Jerry Kaplan, it is argued that AI-driven automation is accelerating this trend by making it more feasible for companies to hire specialized workers on a need-based basis rather than maintaining a full-time workforce.[19]

A PwC report[20] highlights that gig platforms are leveraging AI to match workers with tasks more efficiently than ever before. It predicts that by 2030, the number of full-time permanent jobs will drop significantly, with only 9% of the U.S. workforce engaged in traditional employment. This shift reflects a growing reliance on AI-powered marketplaces that dynamically allocate labor based on demand and skill availability.

The Economic Impact of AI on Gig Work

Robin Hanson’s The Age of Em: Work, Love, and Life When Robots Rule the Earth explores a potential future where AI-driven economies are dominated by “Ems”—brain emulations of highly skilled workers that can be copied and employed indefinitely[21]. While the Em scenario remains speculative, it underscores the potential for AI to reshape labor markets in ways that may further erode job security while simultaneously boosting productivity.

Furthermore, the research paper Technological Forecasting and the Future of Work by Ken Goldberg discusses how AI-driven automation is already altering workforce dynamics. It highlights that cloud-based AI is enabling real-time job matching, further strengthening the gig economy’s reliance on technology.[22]

This transformation is leading to an era where workers must continuously adapt their skills to stay relevant in an AI-driven labor market.

The integration of AI into the workforce is reshaping economic models in ways that demand both optimism and caution.

As Human + Machine emphasizes, AI is a powerful collaborator rather than a replacement, amplifying human skills rather than rendering them obsolete. However, as Humans Need Not Apply and The Age of Em warn, the rise of gig work and AI-driven employment models may also bring instability to traditional career paths.

Governments, businesses, and individuals must prepare for this evolving landscape by fostering policies that support workforce adaptability, reskilling initiatives, and ethical considerations surrounding AI’s role in employment.

The workforce of the future will not be a competition between humans and machines, but a collaborative synergy where adaptability and innovation will determine success.

Preparing for AI-Driven Economies: Policy and Education

A. Education in the AI Era

As we step further into the AI-driven economy, one undeniable reality emerges: the future of work is evolving at an unprecedented pace.

Automation, artificial intelligence, and machine learning are transforming industries, redefining skill sets, and creating a demand for lifelong learning. Yet, this transformation presents not just a challenge but also an opportunity—one that hinges on how we, as a society, reshape education to meet the needs of this new era.

AI and the Fundamental Shift in Future of Jobs

American inventor Erik Brynjolfsson and MIT scientist Andrew McAfee present a compelling argument that AI and automation are not just replacing repetitive manual tasks but also cognitive and decision-making roles. Brynjolfsson and McAfee argue:

“There’s never been a better time to be a worker with special skills or the right education, because these people can use technology to create and capture value. However, there’s never been a worse time to be a worker with only ‘ordinary’ skills and abilities to offer.”[23]

This insight highlights the fundamental shift AI brings: it doesn’t just replace labor; it redefines what is valuable in the workforce. The skills that remain essential are not those that can be automated but those that complement AI—critical thinking, creativity, emotional intelligence, and adaptability.

Similarly, Acemoglu and Restrepo’s research, Artificial Intelligence, Automation, and Work, reinforces this point. They introduce the concept of the displacement effect,[24] which explains how AI-driven automation replaces human labor in existing tasks while simultaneously lowering labor demand.

However, they also discuss the reinstatement effect, which suggests that new roles and tasks will emerge, requiring different skills.

If automation replaces tasks but also creates new opportunities, the primary question is: how do we equip future workers for this transition? The answer lies in a shift from traditional education models to continuous learning and adaptability.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee emphasize that humans must learn to “race with machines” rather than against them:

“The right education, one that fosters creativity, critical thinking, and interpersonal skills, will be key to ensuring that people can work alongside machines instead of being replaced by them”.[23]

Acemoglu and Restrepo support this idea with economic evidence, explaining how technology-skill mismatches can slow down adaptation and increase inequality. [24]This is particularly relevant in developing countries where workforce retraining programs are scarce.

The Role of Reskilling Programs

The importance of reskilling programs cannot be overstated. These programs must:

- Focus on AI-proof skills – such as problem-solving, adaptability, and interpersonal communication.

- Be industry-driven – collaborating with businesses to align curricula with real-world needs.

- Promote digital literacy – ensuring workers can interface effectively with AI tools.

Governments and institutions must adopt a policy-driven approach to reskilling, much like past industrial revolutions required vocational training reforms.

Policy Recommendations for Building AI-Ready Education Systems

Brynjolfsson and McAfee propose a rethinking of education policies to adapt to AI’s rapid development:

“Traditional education systems were designed for a world where knowledge was scarce, and memorization was crucial. Today, we need an education system that fosters creativity, adaptability, and collaboration—skills that AI cannot easily replicate.”[23]

Acemoglu and Restrepo argue that excessive automation can harm productivity growth and economic mobility if not counterbalanced with investments in human capital.

They advocate for policies that:

- Tax automation appropriately to fund worker training programs.

- Encourage public-private partnerships for upskilling initiatives.

- Ensure equal access to reskilling opportunities to prevent widening inequality gaps.

The AI revolution is not a distant future—it is here. The challenge ahead is not AI itself but our ability to adapt to it. As Brynjolfsson and McAfee emphasize, technology alone does not determine our future—our policies, choices, and education systems do.[23]

Acemoglu and Restrepo provide a stark warning: if education and policy frameworks fail to keep pace, inequality will deepen, and productivity gains from AI will be concentrated in the hands of a few. However, if we embrace reskilling, lifelong learning, and adaptable policies, AI can be a tool for economic expansion and human empowerment.

The question is no longer whether AI will change the nature of work—it already has. The real question is: are we prepared for it?

B. Policy Recommendations for Managing AI Disruption

While AI-driven automation offers significant productivity gains and economic growth opportunities, it also presents profound challenges such as job displacement, wage polarization, and skill mismatches.

Managing AI-driven economic shifts requires well-crafted policies that address workforce transitions, enhance labor protections, and foster sustainable economic growth. This section explores policy solutions based on key works by Thomas A. Kochan[25], André Spicer[26], and relevant reports by McKinsey[27] and the OECD.[28]

1. Ensuring Workforce Resilience

AI is reshaping job requirements, necessitating a focus on reskilling and upskilling workers. Kochan[25] emphasizes the importance of investment in human capital as a shared responsibility among government, businesses, and workers. Policies should:

- Encourage public-private partnerships to expand vocational training and lifelong learning programs.

- Implement tax incentives for businesses that provide AI-related training to employees.

- Establish subsidized retraining programs targeting workers in declining industries.[27]

- Schools and universities must integrate STEM, AI literacy, and digital skills into curricula.[26]

- Policies should promote soft skills development (e.g., critical thinking, problem-solving, emotional intelligence) that complement AI automation.[27]

- Increase funding for apprenticeship programs in AI-related fields.

2. Strengthening Social Safety Nets

Traditional social security systems must adapt to the evolving job market:

- Universal Basic Income (UBI) experiments can be piloted to cushion workers displaced by automation.[27]

- Portable benefits for gig and contract workers should be mandated.[28]

- Strengthen unemployment benefits and retraining grants to support displaced workers.

Governments should create AI-driven employment platforms that use machine learning to:

- Provide personalized job recommendations based on individual skill sets.

- Offer AI-powered career counseling.[25]

- Enable faster workforce redeployment to emerging industries.

3. Encouraging Business Dynamism

- Provide tax credits for companies investing in AI-driven productivity enhancements that retain or retrain workers.[27]

- Establish ethical AI governance frameworks ensuring fair labor practices.

- Mandate human oversight in AI decision-making to prevent algorithmic bias in hiring and firing.

- Introduce low-interest loans for AI-driven startups that create employment opportunities.

- Reduce regulatory barriers for small businesses leveraging AI for growth.[26]

- Foster regional innovation hubs to decentralize economic gains from AI.

4. Addressing Wage Polarization and Economic Inequality

Automation disproportionately affects middle-wage workers. Policies should:

- Implement progressive taxation on AI-driven productivity gains to fund worker training programs.

- Raise minimum wages in high-automation sectors to offset wage suppression.[27]

- Encourage collective bargaining and labor representation in AI governance discussions.[25]

- Introduce shorter workweeks with full-time pay models in industries highly affected by AI.

- Develop profit-sharing models where workers benefit from AI-driven efficiency gains.

- Expand public investment in infrastructure projects that generate middle-wage employment.[28]

5. Regulating AI for Ethical Practices

Governments must implement strong AI regulatory policies to ensure ethical deployment:

- Mandate AI transparency in recruitment and workplace automation.

- Enforce anti-discrimination laws preventing algorithmic bias in hiring.

- Require AI ethics training for HR and corporate leaders.

- Implement “AI Impact Assessments” before large-scale automation projects.

- Create regulatory sandboxes for testing AI innovations with labor union oversight.

- Promote global AI labor standards to prevent a “race to the bottom” in automation ethics.

AI-driven disruption presents both opportunities and challenges for the global workforce.

By implementing proactive education reforms, robust social safety nets, inclusive economic policies, and ethical AI regulations, governments and businesses can ensure that AI serves as a tool for shared prosperity rather than exacerbating inequality.

As highlighted by Kochan, Spicer, McKinsey, and OECD research, policies must focus on reskilling workers, protecting vulnerable populations, and fostering economic dynamism to create a future where humans and AI coexist harmoniously in the workforce.

The Road Ahead

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) presents an extraordinary crossroads for humanity.

While AI is poised to revolutionize industries, create efficiencies, and offer untapped economic opportunities, it simultaneously introduces existential threats to job security, decision-making autonomy, and social hierarchies. As Max Tegmark[29] notes “Right now, we face the choice of whether to start an AI arms race, and questions about how to make tomorrow’s AI systems bug-free and robust”.

This part examines how AI is transforming workforce management and the philosophical and practical dilemmas that accompany this shift. Drawing from Life 3.0 by Max Tegmark, Four Battlegrounds by Paul Scharre, and Our Final Invention by James Barrat, we explore the intersection of automation, labor economics, and human purpose in the AI era.

Efficiency vs. Human Jobs

AI’s influence on labor markets is profound and accelerating. Historically, automation has displaced manual jobs while creating new opportunities in emerging fields.

However, AI threatens not only physical labor but also white-collar professions, marking a fundamental shift from mechanization to cognitive automation.

According to Paul Scharre[30], “By one estimate, nearly half of all tasks currently being done in the U.S. economy could be outsourced to automation using existing technology”.

AI-powered systems are now capable of performing complex analyses, medical diagnostics, legal research, and even creative tasks, placing high-skill professions at risk. This leads to an inevitable economic shift where demand for certain skills plummets while others rise exponentially.

Barrat warns that “The rapid recursive self-improvement that enables an AI to bootstrap itself from artificial general intelligence to artificial superintelligence”[31] will radically alter labor markets, potentially making AI-driven automation irreversible.

This suggests that AI-driven workforce disruptions are not just about efficiency; they may permanently alter the human role in economic production.

AI in Workforce Management

With AI-driven management systems, companies can make real-time decisions based on data analytics, predicting employee performance and optimizing workloads. AI can help in:

1. Automating Hiring Processes: AI algorithms can filter resumes, assess personality traits, and predict job performance based on historical data.

2. Performance Monitoring: AI-powered analytics track employee productivity, suggesting optimizations or interventions.

3. Task Allocation & Scheduling: AI optimizes task distribution, ensuring projects are completed efficiently with minimal resource wastage.

However, this level of surveillance and control raises ethical concerns regarding worker autonomy and privacy. Paul Scharre highlights that AI-driven workforce tools could “lead to a creeping tide of techno-authoritarianism that undermines democracy and freedom”.[30]

The Dilemma of Human Purpose

If AI is capable of performing all economically valuable tasks, what role remains for humans? Tegmark raises an essential question: “Can or should we create a leisure society that flourishes without jobs?”.[29] The prospect of a universal basic income (UBI) or government intervention to redistribute wealth in an AI-dominated economy remains a critical area of debate. However, Nick Bostrom posits the same argument in his seminal work Superintelligence.

In his analysis of AI’s future, Tegmark outlines several possible long-term outcomes:

- Libertarian Utopia – AI-generated wealth enables universal prosperity, but with extreme economic stratification.

- Egalitarian Utopia – AI ensures wealth is equally distributed, with universal access to education, healthcare, and leisure.

- Enslaved God Scenario – AI remains under strict human control, though its full potential is never realized.

These visions force us to consider whether AI should be a tool that amplifies human capability or an autonomous entity that replaces us.

Moreover, the Four Battlegrounds highlights how AI is not just a business tool but a weapon in global competition. Countries like the U.S. and China are vying for AI supremacy, investing billions in automation, data collection, and military applications. AI-driven workforce management is, therefore, not just an economic concern but a geopolitical one.

China’s extensive use of AI in governance illustrates a potential dystopian future: “The Chinese government is building a burgeoning panopticon with over 500 million cameras deployed nationwide by 2021, more than half of the world’s surveillance cameras”.[30]

This level of control, if applied in corporate settings, could erode worker rights and personal freedoms.

While AI brings efficiency and economic growth, it also demands responsible governance. Barrat argues that AI “will have its own drives, beyond the goals with which it is created”,[31] suggesting that its evolution may not always align with human values.

Governments, corporations, and institutions must:

- 1. Regulate AI-driven workforce management to ensure transparency and fairness.

- 2. Invest in AI safety research to prevent unintended consequences.

- 3. Redefine work and human value, preparing for a future where traditional employment is no longer the norm.

The road ahead is fraught with challenges, yet full of opportunities. The choices we make today regarding AI deployment in the workforce will determine whether we move towards a world of enhanced human potential or one of widespread displacement and control.

As Tegmark suggests, “We are better off modernizing our laws before technology makes them obsolete”. The responsibility lies with governments, businesses, and individuals to steer AI development in a direction that ensures prosperity for all.

Ultimately, AI should serve humanity, not replace it. The question is not whether AI will change the workforce, but whether we are prepared to shape that change for the better.

List of jobs and Works Threatened by AI Automation

- Manufacturing and assembly line jobs

(Schwab, 2016; Ford, 2015; Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2020) - Transportation (truck drivers, delivery drivers)

(Schwab, 2016; Bostrom, 2014; Russell, 2019; Ford, 2015) - Retail (cashiers, salespeople)

(Schwab, 2016; Frey & Osborne, 2013; Ford, 2015; OECD, 2016) - Administrative jobs (clerks, bookkeepers)

(Schwab, 2016; Frey & Osborne, 2013; Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2019) - Customer service roles

(West, 2018; Lee, 2018; Baldwin, 2019) - Creative roles (artists, writers, musicians)

(Bostrom, 2014; Kurzweil, 1990; Kaplan, 2015) - Scientific research positions

(Bostrom, 2014; Kaplan, 2015) - Call center jobs

(West, 2018; Bootle, 2019) - Legal clerks and paralegals

(West, 2018; Bootle, 2019; Frey & Osborne, 2013) - Medical diagnostics roles (radiologists, lab technicians)

(West, 2018; Wooldridge, 2021; Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2019; Tegmark, 2017) - Mathematical computation and problem-solving jobs

(Turing, 1950) - Certain teaching roles (basic education and testing)

(Turing, 1950; Lee, 2018) - Financial analysts and advisors

(Kurzweil, 1990; Bootle, 2019) - Translators and interpreters

(Kurzweil, 1990; Kaplan, 2015) - Journalists and reporters (automated content generation)

(Kurzweil, 1990; Ford, 2015; Kaplan, 2015) - Accountants and tax preparation jobs

(Wooldridge, 2021; Frey & Osborne, 2013; Ford, 2015) - Insurance underwriting

(Wooldridge, 2021; Ford, 2015) - Agricultural labor

(Kurzweil, 2022; Goldberg, 2020) - Construction workers (through automation of machinery)

(Kurzweil, 2022; Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2014) - Government roles (policy analysis, bureaucracy management)

(Lennox, 2020) - Military personnel (AI-driven defense and surveillance)

(Lennox, 2020; Scharre, 2023) - Logistics and supply chain management

(Lee, 2018; McKinsey & Company, 2021; Baldwin, 2019) - Educational tutors (online and AI-based teaching)

(Lee, 2018; West, 2018) - Legal services (contract drafting, legal research)

(Bootle, 2019; Frey & Osborne, 2013) - Financial services (loan officers, personal financial advisors)

(Bootle, 2019; Ford, 2015) - Telemarketers

(Frey & Osborne, 2013; Bootle, 2019) - Watch repairers

(Frey & Osborne, 2013) - Bank tellers

(Frey & Osborne, 2013; Ford, 2015) - Offshore service jobs (IT support, accounting)

(Baldwin, 2019) - Outsourced clerical work

(Baldwin, 2019) - Routine cognitive tasks (data entry, simple decision-making jobs)

(Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2020; Frey & Osborne, 2013; Bootle, 2019) - Low-skill service jobs (fast food, retail)

(Ford, 2015; Schwab, 2016) - White-collar jobs (lawyers, healthcare administrators)

(Ford, 2015) - Autonomous transportation (e.g., taxis, truck drivers)

(Russell, 2019; Schwab, 2016; Ford, 2015) - Military drone operators

(Russell, 2019; Scharre, 2023) - Software testing

(Mitchell, 2019)

37. Proofreading and copy-editing

(Mitchell, 2019) - Product design and testing

(Daugherty & Wilson, 2018) - Quality control inspectors

(Daugherty & Wilson, 2018) - IT support and infrastructure jobs

(Kaplan, 2015) - Human resources (recruitment and performance analysis)

(Kaplan, 2015) - Personal assistants

(Workforce of the Future, 2017; Frey & Osborne, 2013) - Marketing analysts

(Workforce of the Future, 2017; Daugherty & Wilson, 2018) - Middle management jobs

(Hanson, 2016; Frey & Osborne, 2013) - Traditional academic teaching roles

(Hanson, 2016; Lee, 2018) - Warehouse and fulfillment jobs

- (Goldberg, 2020; Schwab, 2016)

- 47.Routine clerical and sales jobs

(Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2014; Frey & Osborne, 2013 - 48. Hospitality industry (hotel check-ins, waitstaff)

(Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2014; Frey & Osborne, 2013) - 49. Clerks in financial and banking institutions

(OECD, 2016; Frey & Osborne, 2013) - 50. Skilled trades (e.g., welders, machinists)

(OECD, 2016; Schwab, 2016) - 51. Telemedicine roles

(Tegmark, 2017) - 52. Personalized healthcare services

(Tegmark, 2017; Daugherty & Wilson, 2018) - 53. Military logistics and decision-making

(Scharre, 2023; Lennox, 2020) - 54. Intelligence and surveillance analysts

(Scharre, 2023; Kaplan, 2015) - 55. Autonomous vehicles and pilots

(Barrat, 2013; Kurzweil, 2022)

List of jobs and roles that are less likely to be lost to AI and automation

1. Creative Roles

- Writers, Artists, Musicians

- Film Directors and Screenwriters

2. Healthcare and Human Services

- Doctors, Nurses, and Caregivers

- Mental Health Professionals

- Social Workers

3. Education and Training

- Teachers and Educators

- Special Education Instructors

4. Skilled Trades

- Plumbers, Electricians, and Mechanics

- Construction Workers

5. Management and Leadership Roles

- Corporate Leaders and Strategic Managers

- Entrepreneurs

6. STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics)

- AI Developers and Data Scientists

- Robotics Engineers

- Ethical AI Researchers and Policy Developers

7. Human-Centered Roles

- Customer Service in Complex, High-Touch Areas

- Event Planners and Human Experience Designers

8. Environmental and Sustainability Roles

- Environmental Scientists and Conservationists

- Sustainability Consultants

9. Interdisciplinary and Ethical Roles

- Philosophers, Ethicists, and Legal Experts

- Policy Makers and Regulators

10. Artisanal and Craft Roles

- Craftsmen and Artisans

- Culinary Professionals

References

1. The Fourth Industrial Revolution by Klaus Schwab

2. Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies by Nick Bostrom

3. The Future of Work by Darrell by M. West

4. Computing Machinery and Intelligence by Alan Turing (1950)

5. The Age of Intelligent Machines by Ray Kurzweil

6. A Brief History of Artificial Intelligence by Michael Wooldridge

7. The Singularity Is Nearer by Ray Kurzweil

8. 2084: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Humanity by John C. Lennox

9. AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order by Kai-Fu Lee

10. The AI Economy: Work, Wealth, and Welfare in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Roger Bootle

11. The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerization? by Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne (2013)

12. The Globotics Upheaval: Globalization, Robotics, and the Future of Work by Richard Baldwin

13. Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets by Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo (2020)

14. Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future by Martin Ford

15. Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control by Stuart Russell

16. The Alignment Problem: Machine Learning and Human Values by Brian Christian

17. Artificial Intelligence: A Guide for Thinking Humans by Melanie Mitchell

18. Human + Machine: Reimagining Work in the Age of AI by Paul Daugherty and H. James Wilson

19. Humans Need Not Apply: A Guide to Wealth and Work in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Jerry Kaplan

20. Workforce of the Future: The Competing Forces Shaping 2030,

21. The Age of Em: Work, Love, and Life When Robots Rule the Earth by Robin Hanson

22. Technological Forecasting and the Future of Work by Ken Goldberg

23. The Second Machine Age by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee

24. Artificial Intelligence, Automation, and Work by Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo

25. Shaping the Future of Work: A Handbook for Action and a New Social Contract by Thomas A. Kochan

26. AI and the Future of Work by André Spicer

27. McKinsey’s AI, Automation, and the Future of Work by McKinsey & Company

28. The Risk of Automation for Jobs in OECD Countries by OECD

29. Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Max Tegmark

30. Four Battlegrounds: The Fight for the Future of AI by Paul Scharre

31. Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the End of the Human Era by James