Last updated on October 31st, 2023 at 02:12 pm

The current crisis of Rohingya in Bangladesh, 2017, which has taken shape as a self-inflicted wound demands a thorough understanding of the real gainers and losers from it. Myanmar’s strategy to capitalise on the Rohingya crisis may severely harm Bangladesh’s domestic interests in various forms. Will Bangladesh ever be able to repatriate the Rohingyas? Is Bangladesh a victim of global politics?

Crisis of Rohingya: Who are the Rohingyas

The Rohingya people are an ethnic minority that lives mainly in the northern region of Rakhine State, Myanmar. Even though they identify themselves as Arab descendants who settled in the 7-8 century, they are, however, according to French Scholar Jacques Leider, the descendants of migrated Muslims from Bengal to Rakhine. Until the 1990s they were referred to without controversies as Bengalis Muslim, ‘Chittagonians’ or ‘Mohammedans’ as a whole.

Scottish physician, geographer, zoologist, and botanist, Francis Buchanan, who served as a surgeon in the Kingdom Ava wrote in his ‘A Comparative Vocabulary of Some of the Languages Spoken in the Burma Empire, that “the Mohammedans, who have long settled in Arakan, and who call themselves Rooinga, or natives of Arakan (now Rakhine).

Historian Aye Chan wrote, “In the early 1950s that a few Bengali Muslim intellectuals of the north-western part of Arakan began to use the term “Rohingya” to call themselves” denoting the ‘People of Arakan’. “The creators of that term might have been from the second or third generations of the Bengali immigrants from the Chittagong District in modern Bangladesh. It should be noted that all the Chittagonians and all the Muslims are categorized as Mohammedan in the census reports”.

Again, as historian Aye Chan says Muslims in the Rakhine region came in the 1st millennium. Muslim community’s expansion and the growth of Islam into the region came much later with Bengali Muslims from the region that is now a part of Bangladesh. Further, the term “Rohingya” does not appear in any regional text of this period and much later.

The conflicts of Rohingyas against the state of Myanmar calls for its roots in its history. Islam in Myanmar arrived through Arabian traders, Muslim settlers, military personnel, prisoners of war, refugees, and slaves during the 7th century in Arakan, Maungdaw and the Arab traders who were also missionaries started Buddhist conversion during the 8th century. These missionaries got settled by marrying local women in Arakan.

Arabs, Persians, Turks, Moors, Indian-Muslims, sheikhs, Pakistanis, Pathans, Bengalis, Chinese Muslims and Malays who settled and intermarried with local Burmese and many ethnic Myanmar groups such as Rakhine, Shan, Karen, Mon, etc. were the ancestors of the current Muslim population of Myanmar.

Another historical evidence found that early Bengali Muslims settlement in Arakan back to the time of the last king Min Sam Mon of Launggyet Dynasty of the Kingdom of Mrauk U in 1433-34. After being driven by Crown Prince Minye Kyawswa of Ava he sought refuge in the Bengal Sultanate and spent 24 years of banishment in Bengal. He came back when he regained control over the Arakanese throne in 1430 along with Bengali military assistance from Sultanate. The Bengali companion who accompanied his return settled in the region.

The population increased in the 17th century, as slaves were brought in by Arakanese raiders and Portuguese settlers following raids into Bengal. Slaves included members of the Mughal nobility. The slave population was employed in a variety of workforces, including in the king’s army, commerce and agriculture.

When the second-largest empire, the Konbaung Dynasty, of Burma that ruled Burma from 1752 to 1885 conquered Arakan in 1785, as many as 35,000 people from Rakhine State fled to the neighbouring British Bengal Chittagong region in 1799 to avoid persecution by the Burmese dominant majority Bamar. The Bamar executed thousands of men and deported a considerable portion of people from the Rakhine population to central Burma, leaving Arakan a scarcely populated area by the time the British occupied it. Are these 35,000 Muslims already here in Bangladesh? Or returned and spread across Myanmar?

Having said that, when Burma was under British colony it encouraged Bengali farm labourers for the lightly populated and fertile valley of Arakan. The East India Company extended the Bengal Presidency to Arakan. There was no international boundary between Bengal and Arakan and no restrictions on migration between the regions. In the early 19th century, thousands of Bengalis from the Chittagong region settled in Arakan seeking work.

In his research article ‘The Development of a Muslim Enclave in Arakan (Rakhine) State of Burma (Myanmar), historian Aye Chan of Kanda University of International Studies says, “The migrations were mostly motivated by the search of professional opportunity. During the Burmese occupation, there was a breakdown of the indigenous labour force both in size and structure. In the 1830s the wages in Arakan compared with those of Bengal were very high.

Therefore many hundreds, indeed thousands of coolies came from the Chittagong District by land and by sea, to seek labour and high wages. The flow of Chittagonian labour provided the main impetus to the economic development in Arakan within a few decades along with the opening of regular commercial shipping lines between Chittagong and Akyab. The arable land expanded four and a half times between 1830 and 1852 and Akyab became one of the major rice exporting cities in the world.

But the account does not affirm whether those new Bengal migrants were the same people who were deported during Konbaung Dynasty to the neighbouring British Chittagong region or the same people, and later returned to Arakan due to British policy.

Professor Andrew Selth of Griffith University says that although a few Rohingya trace their ancestry to Muslims who lived in Arakan in the 15th and 16th centuries, most Rohingyas arrived with the British colonialists in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Combined with Indian, Chinese and Burmese Muslims the total Muslim population rose to 584,839, which is 4% of the total population, as per the 1931 census. 41% of the Muslim population lived in the Arakan region.

Began in 1940 when the Japanese invasion of Southwest Asia erupted Arakan happened to be at the frontline in the conflict. Japan’s advance in the region resulted in an inter-communal conflict between Arakanese Buddhists. Consequently, the Muslims had to take refuge in the British-controlled Muslim-dominated northern Arakan from the Japan-dominated Buddhist majority area. This hostility breeds a “reverse ethnic cleansing” in the British-controlled Muslim-dominated northern Arakan, especially in Maungdaw. British failure of counterattack resulted in the abandonment of the Muslim population and increased communal violence from 1942 to 1943.

This communal hostility spread in many parts of Burma as a result of the British retreat. As the Japanese advanced into Arakan Buddhists inflicted cruelty against Muslims and thousands from Buddhist majority regions fled to eastern Bengal (now Bangladesh) and northern Arakan while many were killed. Responding to the Buddhist-inflicted hostility, Muslims in the British-controlled areas conducted retaliatory action causing them to flee from northern Arakan.

During WWII, when the Japanese Imperial Army invaded British-controlled Burma the British forces fled creating a power vacuum behind which had given rise to communal violence between Arakanese and Muslim villagers. The British supplied armoury to Muslims in Northern Arakan to create a defence zone aiming to protect the region from Japanese invasion and counterattack the pro-Japanese Rakhines ethnic.

Aye Chan, a historian at Kanda University in Japan has written that as a consequence of acquiring arms from the British during World War II, Rohingyas tried to destroy the Arakanese villages instead of resisting the Japanese. Chan agrees that hundreds of Muslims fled to northern Arakan, though states that the accounts of atrocities on them were exaggerated. In March 1942, Rohingyas from northern Arakan killed around 20,000 Arakanese. In return, around 5,000 Muslims in the Minbya and Mrauk-U Townships were killed by Rakhines and Red Karens.

Moreover, the root cause of conflicts, perhaps, lies within Rohingya Muslims, who were allied with the British who promised them a Muslim state in return, fought against local Rakhine Buddhists, who were allied with the Japanese. But the promise of an independent Muslim state did not come to fruition because of the British retreat. Following the independence of Burma in 1948, the newly formed union government of the predominantly Buddhist, country denied citizenship to the Rohingyas.

Coupled with British retreat and disappointment, before Burma’s independence, in 1946, Muslim leaders from Rakhine State (then Arakan) met with the founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah and asked him to annex Buthidaung and Maungdaw of the Rakhine State with Bangladesh (then East Bengal). The North Arakan Muslim League founded in Sittwe (then Akyab) after two months of meeting with Jinnah made the same appeal. But Jinnah refused the proposal because he did not want to interfere with Myanmar’s internal affairs. Muslims from Arakan now approached the Myanmar government asked for its concession of the two towns to Pakistan. The Burmese parliament rejected the appeal.

From 1947 Muslim separatist mujahedeen fought the Myanmar government for an autonomous Rohingya-populated region in northern Arakan (now Rakhine) which was predominantly Muslim oriented and under British control before Myanmar’s independence. They wanted to annex the region to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). The mujahedeen lost its momentum during the 1950s and 1960s which resulted in their mass surrender.

Later, the Rohingya Independent Front (RIF) was formed in 1964 in a view to forming an autonomous Muslim zone for Rohingya people. The name was changed to Rohingya Independent Army (RIA), and Rohingya Patriotic Front (RPF) in 1969 and 1973 consecutively. With a medical doctor, RPF had around 70 fighters. The attack came as a retaliation to the authority’s introduction of Emergency Law.

The most influential separatist group of Rohingya, the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation (RSO) was recreated from the Rohingya Patriotic Front (RPF) in 1982 with support from various Islamist groups such as Jamaat-e-Islami, Hizb-e-Islami, Hizb-ul-Mujahideen, Angkatan Belia Islam sa-Malaysia, and the Islamic Youth Organisation of Malaysia.

Rohingya Solidarity Organisation (RSO)’s fighting against the Myanmar authority triggered a massive military operation named Operation Dragon King in 1978. And it was behind the attack of Burmese authorities near the Bangladesh- Myanmar border which culminated in the nation’s first Rohingya exodus. 200,000-250,000 Rohingyas took refuge in Bangladesh.

Owing to the Myanmar military’s failure to disarm RSO through “Operation Clean and Beautiful Nation”, it remained a full-blown armed separatist in the region. An interview conducted by correspondent Bertil Lintner in 1991 of Rohingya military camps in Cox’s Bazar revealed that RSOs relocated camps in Cox’s Bazar was filled with an arsenal of light machine guns, AK-47 assault rifles, RPG-2 rocket launchers, claymore mines and explosives. The arm expansion of RSO triggered the Myanmar government a military offensive ‘Operation Clean and Beautiful Nation’ in 1991. By 1992 the second Rohingya exodus took place. This time too more than 250,000 took shelter in Bangladesh.

A new insurgent group Harakah-al-Yaqin attacked Myanmar border security posts near the Bangladesh- Myanmar border in 2016 causing bloodshed that took 40 combatants. Furthermore, Harakah-al-Yaqin with a renewed name, Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, attacked 30 Myanmar security posts in August 2017 causing 71 dead. The aftermath of the attack resulted in the third and the largest Rohingya exodus. As a result, regions of Myanmar, as per Myanmar Population and Housing Census 2014, subsequent military crackdown drove 700,000 plus Rohingyas into neighbouring Bangladesh. The crackdown is responsible for 24,000 deaths, 18,000 rapes of Rohingya women and girls, 116,000 beaten and arson victimisation of 36,000 Rohingyas.

But how justified is Myanmar’s action toward the Rohingya population who have been living in Myanmar for generations in making them stateless? It is undeniably a strong fact that most of the Rakhine Muslims have Bengali ancestry who migrated to Arakan during British Colonial time or even before that. Economic and political migration also took place in South Africa during the British Empire, in the early 20th century when thousands of Indian Hindu-Muslim labourers or settlers got settled in South Africa.

Indian Africans who fought and severed imprisonment with Nelson Mandela faced unfair treatment from locals. Faced harsh racism but after independence, Indian African were assimilated into the mainstream population and the question of ‘statelessness’ was never there in the minds of Africans.

Perhaps Rohingya Muslims’ alliance with the British, aspiration of an independent Muslim-dominated Arakan and insurgency of separatists begotten a different scenario, unlike South Africa.

Rohingya citizenship

Encyclopedia Britannica defines citizenship as, the “relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection”. But, according to the 1982 Burmese Citizenship Law, three categories of the people of the country qualify for citizenship rights: Citizens, Associate Citizens, and Neutralised Citizens.

1 . Genuine citizen: Those people who resided before 1883 (before the end of the last dynasty of the Burmese Empire). The national races are (Kachin, Kayah (Karenni), Karen, Chin, Burman, Mon, Rakhine, Shan, Kaman, or Zerbadee) or whose ancestors settled in the country before 1823, the beginning of the British occupation of Arakan State.

2 . Associate citizens: If a person cannot provide evidence that his ancestors settled in Burma before 1823, he or she can be classified as an associate citizen if one grandparent, or pre-1823 ancestor, was a citizen of another country. Those persons who qualified for citizenship under the 1948 law, but who would no longer qualify under this new law, are also considered associate citizens if they had applied for citizenship in 1948. These people originated mainly by mixed marriage with immigrants and indigenous Burmese after 1823.

3 . Neutralised citizens: sections 42-44 of Burma Citizenship Law 1982 describes, Persons who have entered and resided in the State prior to 4th January 1948, and their children born within the state may, if they have not yet applied under the Union Citizenship Act, 1949, apply for neutralised citizenship to the central Body, furnishing conclusive evidence.

To become a naturalized citizen, a person must be able to provide “conclusive evidence” that he or his parents entered and resided in Burma prior to independence in 1948. For a person to have neutralised citizenship a person must (a) be a person who conforms to the provisions of section 42 or section 43: (b) have completed the age of eighteen years; (c) be able to speak well one of the national languages: (d) be of good character; (e) be of sound mind.

Unfortunately, Rohingya Muslims qualify for neither of the citizenship categories. Even though Muslims’ history in Myanmar goes as far back as the 7th century they cannot be genuine citizens of the country because of their skin colour and language. None of the Muslims in Rakhine State will be able to produce any residency documentation related to their citizenship of time before British hegemony when most of the scholars believe that Arakan Muslims have Bengal ancestry. Associate citizenship is not possible for them nor the neutralised one. Are Rohingyas victims of the British hegemony of Arakan?

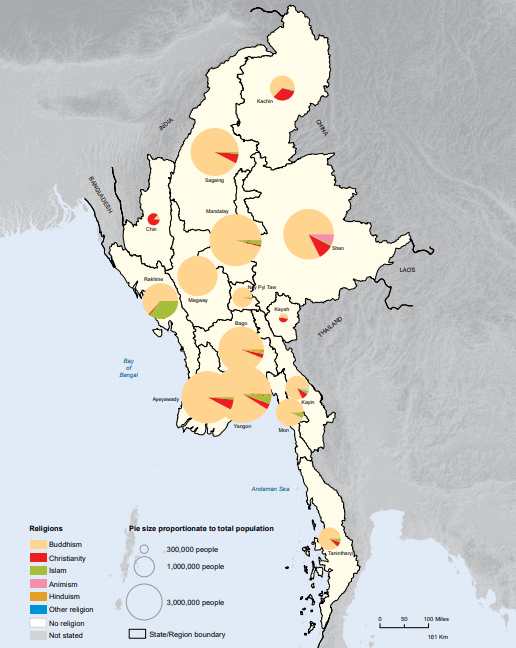

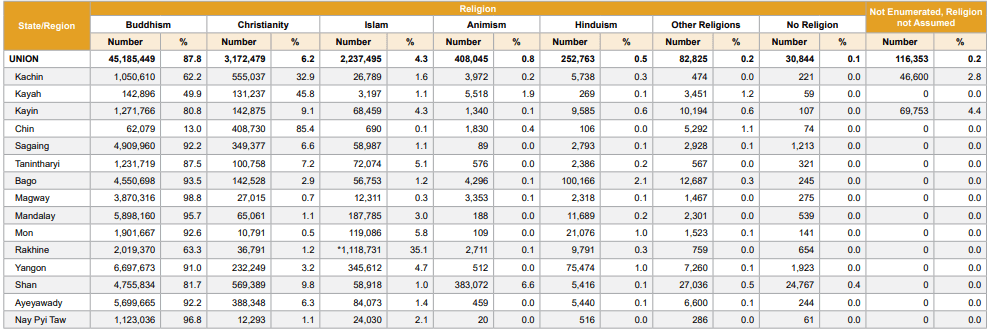

According to Myanmar’s census, the 2014 Muslim population does not exist only in the Rakhine region. Of the enumerated and estimated total of 51 million-plus population 4.3 per cent are Muslims, 6.2 per cent are Christians, Hindus 0.5 per cent while the majority of Buddhists are 87.8 per cent. Followed by 35.8In 15 Unions only Rakhine state is the Muslim-oriented union with 35.1 per cent. With Tanintharyi state, the second-highest among the states, 5.1 per cent of Muslims in all states have the presence of Muslims in Myanmar. Except for Muslims in Rakhine state, the rest of the Muslims I hope do have an ancient link to their ancestors.

Therefore, in a sense, it is to be concluded that the current Myanmar government is supposedly not against Muslims, but against a particular section of them which either has a basis on national security or political or economic interest in the Rakhine state.

Below, I will explore the latest influx scenario from an observer’s perspective. No matter what we think the real cases responsible for the exodus that has created the greatest humanitarian crisis, we will take into consideration the facts such as the socioeconomic, health, environmental, and national security, the huge business that has been running, the profiteers, the losers and China’s capitalising the crisis.

Rohingya refugees

Instead of diving into the multifaceted facts behind the exodus, let us have a glimpse of how it has been played and the impact on innocent people of the Rakhine State.

As we have seen the largest and the third exodus of Rohingyas to Bangladesh began after the 25 August 2017 military crackdown on Rohingya Muslims following insurgent attacks on 30 military security posts that killed 71 security personnel. As a result, more than 725,000 ethnic Rohingyas fled to Bangladesh.

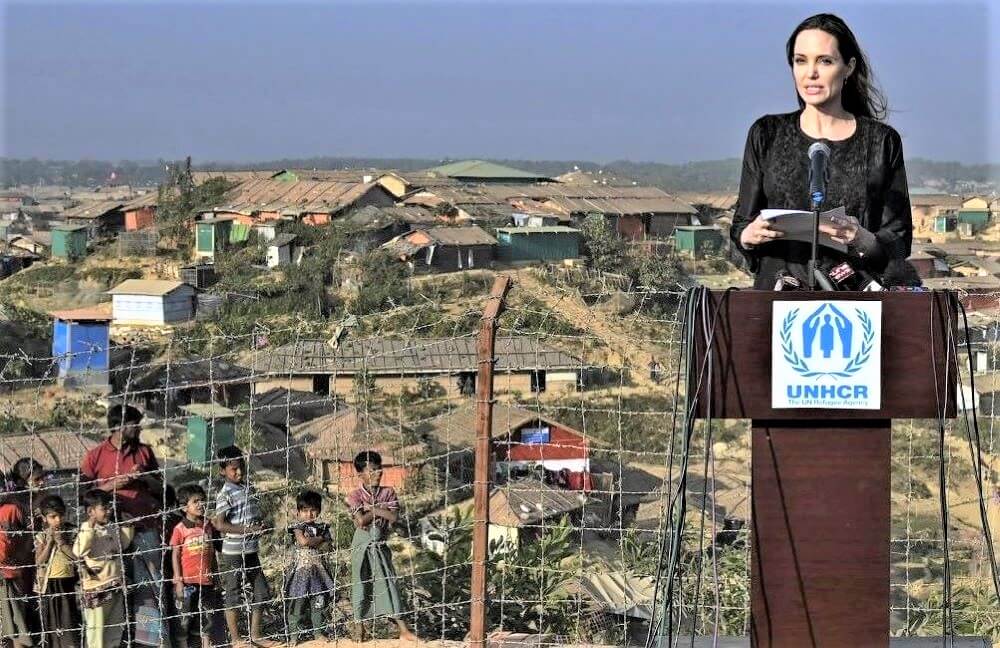

Making the Kutupalong-Balukhali mega refugee camps the biggest, the population taking refuge in the area have become over 1 million, added up to the already existing 250,000 refugees from the previous influx. The campaign by the Myanmar government ignited an ethnic cleansing in the Rakhine state of Moungdhow. Along with killing, rape, torture and putting Rohingya houses on fire by the military, the crackdown incited the biggest exodus of humanity on the planet.

Rohingyas, who are a predominantly Muslim minority have been living in Myanmar for hundreds of years and have been stripped of citizenship by the military ruler of the country in 1982. The country’s large scale campaign of killing, rape and other forms of sexual violence amounting to crimes against humility caused a humanitarian crisis in Bangladesh. Being populated it still allowed this staggering number of people merely on humanitarian ground.

Human Rights Watch has documented the Myanmar security force’s use of gang rape and other forms of sexual violence against Rohingya women and girls as part of the 2017 ethnic cleansing campaign. Sexual violence, including the use of rape targeting an ethnic group or other population, often leads to physical and serious mental health complications for survivors, including post-traumatic stress disorder, complex trauma, anxiety, or depression.

The suffering and ordeal of the people in the camps were inexplicably bad. According to UNICEF, there are 1.2 million people in need – including both refugees and the host community, 683,000 Children in need of humanitarian assistance. In May, 164 weather-related incidents were reported affecting 50,840 individuals in camps including landslides, wind, rain, fire, and lightning. A total of 28 Collective Sites and 99 locations with a dispersed setting in host communities.

According to Human Rights Watch’s report ‘Bangladesh is not my country’,” As of June 10, 2018, about 215,000 refugees in the Cox’s Bazar area were at risk of landslides and flooding, with 42,000 at highest risk, The mega camp is severely overcrowded. The average usable space per person is 10.7 square meters per person, whereas the recommended international standard for refugee camps is 45 square meters and should not be less than 30 square meters per person. Densely packed refugees are at heightened risk of communicable diseases, fires, community tensions, and domestic and sexual violence.

UNICEF’s Humanitarian Situation Report 51, August 19 found 42,000 children aged 6-59 months with severe acute malnutrition (SAM). Provided 15,971 health consultations facilities children were found to be suffering from diarrhoea and various diseases.

While Myanmar is responsible for creating the humanitarian crisis that has ended up in Bangladesh, it has signed a repatriation deal with the government of Myanmar. And Myanmar’s failure to take any meaningful actions to address either recent atrocities against the Rohingya or the decades-long discrimination and repression against the population is at the root of delays in refugee repatriation.

Bangladesh’s handling of the refugee situation needs to be understood in the context of Myanmar’s responsibility for the crisis. The Rohingya’s identity as nationals of Myanmar motivates their preference for repatriation as well as conditioning their return on being granted citizenship and recognized as Rohingya.

No matter what the international community’s urge about the forcibly displaced Rohingyas, Myanmar’s inaction, lack of cooperation and its sturdiness speaks volumes of its intention regarding possible repatriation of Rohingya people. Will they ever be able to go back to their land? Or Bangladesh will be forced to accept them as Bengalis provided the financial assistance by the Myanmar-Chinese government?

The research journal of social science titled, Rohingya Issue: Changing Nature of Geopolitical Situation and Diplomatic by Dr Kuntal Kanti Chattoraj, Department of Geography of P.R.M.S. Mahavidyalaya describes three important phases of the Rohingya exodus in history.

Phases of Exodus

Phase 1: The first exodus broke out in 1978 after Myanmar introduced the Emergency Immigration Act in 1974 to check identity papers of the border region population. As a result, 200,000 -250,000 Rohingyas fled to Bangladesh. But Myanmar agreed to repatriate 200,000 after a long dialogue and mounting pressure from the United Nations, the government of Saudi Arabia, India, and the World Muslim League.

Phase 2: The second phase of the exodus took palace in April 1991 and May 1992 because of the operation against the Rohingya freedom movement. This time too more than 250,000 took shelter in Bangladesh. Pressurised by UNHCR Myanmar agreed to take back only 60,000 Rohingya.

Phase 3: The current and third phase of the exodus took place in the aftermath of 30 military personnel’s deaths at the security posts in the attacks carried out by the Rohingya extremist group Arakan Salvation Army (ARSA) on 25 August 2017. Ultimately, the country’s army-led “clearance operation” drove more than 700,000 population from Rakhine state to neighbouring Bangladesh making the number as large as a million-plus along with those who have already been living.

Amid the outcry and humanitarian crisis of Rohingyas China’s skilful diplomacy exploited the situation to its interests which were apparent in its stance with Russia to veto a United Nations Security Council statement about the human rights issue in the region.

In November 2017 Beijing arranged a friendly meeting with Aung San Suu Kyi and Myanmar’s chief of armed forces General Min Aung Hlaing with Chinese President Xi Jinping where China came up with its own version of strategy to deal with the Rohingya crisis, calling for a cease-fire, cooperation between Bangladesh and Myanmar to repatriate refugees. The voluntary return of the ‘Verified’ refugees through documentation was a part of the deal which is exactly what Myanmar wanted.

China’s One Belt One Road Dream

Chinese influence in Rakhine is primarily economic, and there are two significant and controversial projects in the state: the Kyaukpyu Special Economic Zone, and gas and oil pipelines that cross from Rakhine to China’s Yunnan province which has been completed in April 2017. It links the western coast of Myanmar on the Bay of Bengal to Yunnan province of China.

The line is capable of transporting of 12 million metric tons of oils and 12 million cubic metres of gas every year, and a consortium of China’s CITIC as well set to have a 70 per cent share in a $7.2 billion deep-sea port in the Rakhine region. Because, considering China’s $1 trillion ‘One Belt, One Road’ infrastructure initiative would boost development in its Yunnan province and would provide direct access to the Indian Ocean once a Friendly Myanmar is on its side.

Both projects reflect China’s ambition for greater access to the Indian Ocean as well as the increased global connectivity this could provide. Both projects have since been linked to the Belt and Road Initiative or ‘One Belt, One Road’ or BRI, announced in 2013. As China hopes to import oil from Myanmar bypassing the Strait of Malacca which is the main shipping channel between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, one of the most important shipping lanes in the world, it is imperative that it maintains peace in order to keep the USA at bay in the region.

China’s relation with Aung San Suu Kyi National League of Democracy deemed better than the country’s previous governments, especially when Thein Sein who had Western ties and suspended the construction of USD 3.6 billion worth of Myistone Dam in northern Myanmar because of china’s exploitative manner through its investment in Myanmar.

A study conducted by the United States Institute Of Peace under ‘Understanding China’s Response to the Rakhine’ explains that “the political relationship has improved since 2015, and more recently, as the active conflict has increased between the Tatmadaw and ethnic armed groups on the China-Burma border, China has found itself playing a greater facilitation role in Burma’s peace process.

In recent years, China has attempted to proactively define its relationship with Burma as a “friendly neighbour” interested in pursuing connections where it believes the two countries’ interests align—a strategy that can be clearly seen in its interventions in Rakhine.

Politically Myanmar has to stay on China’s side. No matter how independently Myanmar seems to pursue the peace process dealing with Bangladesh will still abide by China’s lead.

From the economic presumption, the current crisis is an economic one, at least this is how China tends to see. Underdevelopment, unemployment, lack of level-playing field for the local political party, inequality and lack of participation in the political institution have fuelled the hostile environment between the Rakhines and Burmese government. As it is an economic problem, so does it require an economic solution which China in the lead to do so by investing in the Rakhine region.

“On November 19, Foreign Minister Wang Yi announced plans for a China-Myanmar Economic Corridor, stretching from Yunnan via Mandalay to both Kyaukpyu and Yangon, as well as a “three-point plan” that, in addition to calling for a cease-fire and the repatriation of Rohingya refugees, identified economic underdevelopment as the root cause of problems in Rakhine and called on the international community to focus on investment in the state”, the study says.

The solution to Crisis: Promises that all we got

Secretary of State of the USA in April this year reiterated its stand by Bangladesh in finding a permanent solution to the refugee crises. In June the Japanese ambassador to Bangladesh said that his country will stay beside Bangladesh. Being agreed with the view that the Rohingya crisis in Bangladesh is not only a problem of Bangladesh, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in early January said ‘it’s a serious threat issue to the whole South Asia. Modi promises India’s support for Bangladesh on the Rohingya issue.

A few days before the first anniversary of Myanmar’s brutal atrocity against Rohingyas, the country’s defector leader, 1991 Nobel Peace Prize Winner, Aung Sung Suu Kyi said, ‘that it was up to Bangladesh to decide how quickly the repatriation process to be completed. At the same tune, Myanmar again blamed Bangladesh for another failed repatriation attempt that took place on August 22 this year.

On November 23, 2017, Bangladesh and Myanmar signed a deal for the possible repatriation of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya and 30-member Joint Working Group on December 19, 2017. No tangible progress has been in the sight because of Myanmar’s stubborn position against the deal. Even though Rohingyas want to be repatriated unless their right of citizenship is granted, the property is returned and the freedom of movement in the country is given to them that will not happen.

However, responding to the deal Myanmar agreed to take back Rohingyas only as “foreigners” or “Bengali Muslim citizens”, not a minority ethnic group of the country. Myanmar’s foreign minister U Nyan Win once vehemently said that Myanmar is willing to return of refugees from Myanmar if they are listed as Bengali Muslim minority, but would not accept if they refuge to be listed so because Rohingyas are not Myanmar citizens. So deporting them become easy when the situation resurfaces.

Myanmar, however, agrees to take back only the “Verified refuges” which amount to just around 4,000, through a verification process as the 1948 citizenship Act. In order to do so, Rohingyas have to produce expired National Cards and any residency documents of their ancestors which for most of the Rohingyas is impossible to prove. Moreover, Myanmar had agreed to accept 1,500 Rohingyas each week which will take more than a decade to repatriate more than a million people.

Myanmar authority’s intentional deprivation of valid documents to Rohingyas is deliberate and arbitrary as it resounds obvious that without proof of their residency in Myanmar, they will not be able to return to their own country.

Instead of finding a viable solution to the Rohingya crisis, Myanmar is carrying out sinister propaganda against Bangladesh to the international arena that repatriation is being delayed because of its non-cooperation. However, without any headways towards the solution of the crisis, the military Janta has seized the power once again and started controlling the state, as of February in 2021 kicks off.

Along with the existing economic burden that Bangladesh is already pressured under in dealing with the prevailing crisis, the prolonged stay will incur a severe economic fall-out on the country’s shoulders.

The economic burden of the Rohingya crisis

In a meeting in 2018 International Chamber of Commerce of Bangladesh opined that the Rohingya situation has created pressure on the economic and overall security of the country. It also cites that the crisis cost the country USD 86.67 million worth of forestland of 6800 acres.

As Bangladesh’s future development depends on some critical projects in Chittagong, the latest influx of Rohingya refugees has caused fresh pressure on the country’s economy and security. With the influx, experts’ findings say that the country is at the risk of increased military expenditures which may hamper the country’s development activities. Along with unemployment in the host area, the price of coarse rice has reached a 44 per cent high already.

The Refugee Crisis in Bangladesh has cost the country around 90 million dollars worth 6,800 acres of forestlands.

From the attitude of the international community and the government of Myanmar, it is obvious that Bangladesh will have to carry on the burden of the refugees for a prolonged period of time regardless of economic implications on the population of the country. If from the global refugee experience, the average repatriation time is 10 years then Bangladesh will have to pay a hefty price for showing humanity being the Least Developed Country with less than 1,274 dollars Gross National Income per capita.

Compassion Fatigue

ISCG’s (Inter Sector Coordination Group) Join Response Plan 2019 Funding Updates shows the gloomy picture of dwindling fund trends. It was able to collect 69 per cent of the requested 951 million dollar funds in 2018 while it was able to collect only 302 million dollars out of 920 million making it only 33 per cent of the requested funds this year.

Sectors such as Protection, Health, Site management, Emergency telecommunication, Nutrition, Communication with communities, Shelter and Non-food Items, Wash, Logistic and Coordination could not collect not even half of the required funds with Food and Education to be the highest gainer with 33 and 35 per cent, respectively.

Compassion fatigue among the donor agencies and donor countries is obvious. Not only did the international community lend financial support to Bangladesh they also did provide moral support by raising the Rohingya issue at the international forum. Thanks to the Bangladesh government’s pro-refugee stance international donors and aid agencies NGOs and INGOs have been performing the humanitarian activities smoothly.

But donor fatigue led by Compassion Fatigue has been playing a role among the donor countries and donor agencies recently. The prevailing trends of declining funds may happen because of priority shifts and a lack of resources. In an unstable world where humanity is faced with a constant struggle of maintaining existence over a weaker race or nationality, new humanitarian precedence takes place every day somewhere around the world. Therefore, the priority shift takes place anytime, anywhere.

The new form of humanitarian necessity always trumps the older one. This priority value could happen on either financial or psychological grounds. It is a world where everyone rushes to attend a competing priority on a continuous basis.

According to Wikipedia, “Compassion fatigue, also known as secondary traumatic stress (STS), is a condition characterized by a gradual lessening of compassion over time.

Where, according to the Centre for Policy Dialogue, a Bangladeshi Think Tank, if the Rohingyas have to stay five years from 2018-2023 it will incur a total of 7,046 million US dollar loss. It is USD 17,204 million if they stay for ten years. According to the World Food Programme, it takes around USD 800,000 to feed one million-plus Rohingya every day. What if they will never be repatriated?

USD 800,000 dollars is needed every day in order to feed 1 million-plus Rohingyas in Bangladesh.

In a situation like this Bangladesh will have to take bear the burden of costs. How will Bangladesh be able to maintain the requirement of Rohingyas in such a situation if it ever arises?

According to COAST, only a few people are being benefitted, especially the employees of the UN and INGOs, some high-salaried employees of local and national NGOs, landlords, warehouse and building owners, 3 to 5-star hotels and the vehicle renting business.

Cox’s Bazaar is a traditional tourism destination within Bangladesh, but the refugee influx will negatively impact tourism revenue to the area. Researchers say that the high number and prolonged residence of refugees increase the rate at which land and resources are used up. The local labour market has already been eroded and the host community’s inability to cope with the current low-rate labour wage has given rise to increased unemployment. Nonetheless, given the vast scale of the current influx and the likely protracted nature of the crisis, Bangladeshis have serious worries about its economic toll in the near future.

Aid, waste and mismanagement

Even though the existing living condition of Rohingya refugee in the camps does not meet the international humanitarian standard in a resource-strained country, the question that must be asked is, how much the non-food aid items help mitigate the misery of the Rohingya people? Whose purpose does the Rohingya crisis serve most? Do the donor agencies and the NGOs and INGOs working in the camps do humanitarian work as per the Rohingya context of needs? Or have some NGOs found the crises a way of prospering themselves?

Non-food items such as bathing soaps, laundry soaps, sponge sandals, hand gloves, Harpic, and liquid soaps are next to unnecessary to Rohingya people who are not aware of their uses. Not only are they non-contextual items, but they also have been distributed disproportionate and unrealistically of high quantity. Every household in every two months period gets 39 bathing soaps, 21 laundry soap, 4 pairs of sponge sandals among other non-food items. While Rohingyas find hardly useful materials like hand gloves, Harpic toilet cleaner and liquid soaps most of the time they sell them out to local grocery stores.

Where every household was supposed to get one ration card, many Rohingya families collect ration against multiple ration cards by registering multiple ration cards in the same family. Through this clever endeavour, they sell many humanitarian relief items outside the camps. A report circulated that, Rohingyas are blessed so overflowing that they rather sell it out to a middleman who later sells them in the street corners in the city like Chittagong. That obviously includes food and non-food items such as rice, lintel, vegetables, sugar, cooking oil, milk and so.

Because of lack of involvement, local authority or lax monitoring policy and non-contextual dealing, the greed of local syndicalism are at play currently. This syndicate collects the relief items at as low as one-third of the market price and accumulates them at multiple places so their accumulation may not suspicious to the authority. Later the items are sold at half of the prevailing market value. Therefore, the dealing with Rohingya situation and response operations are being standardised in maintaining international level by lavishly providing them with materials which are mostly non-contextual, irrelevant, useless and wasteful.

Mismanagement and ill-governance of the local contractors and NGOs are apparent in their payment for an exorbitant price. Construction of a latrine and installing tube-well usually cost TK 30,000 t0 40,000 which now costs more than TK 100,000. Contractors usually take permission of constructing a tube-well of 700 feet, but the tube-wells that have been constructed are no more than 300 feet deep which lead them dysfunctional within a short period of time. Speaking of which, if such a trend of fund draining continues in no time will be added dearth of funds.

Coupled with the current dwindling level of funds and spiralling trend overhead wasteful management of finance will lead to a heavier economic burden on Bangladesh’s shoulders in the near future.

Foreign aid agencies spent USD 1500 million in hotel bills in just 6 month period of time, while only 25% of the aids was on refugees.

According to UNHCR, around 172 thousand Rohingya families are living in the camps, the total number of refugees is 739 thousand. Within the framework of JRP 2018 $727 million is raised so far. It means $351 per month ($ 4,217 per year) could have been allocated for each Rohingya family. Nearly 600 vehicles are being used in the Rohingya response. Are these demand-driven or supply-driven? Whose purpose is being served most?

Media report found that foreign aid agencies spent USD 150 million hotel bills in just six-month periods, while only 25 per cent of the aid spent on the refugees took shelter in Bangladesh. Coastal Association for Social Transformation Trust (COAST) in a discussion in association with OXFAM unveiled that nearly 3000 registered and unregistered foreign expatriates are working under INGOs and every aid work gets around USD 400 daily apart from their regular remuneration. Moreover, 130 national and international NGOs are working in the camps employing thousands of aid workers with a hefty salary which is way above than average national wage scale.

Security threats to Bangladesh

The Bangladeshi government’s decisions to allow refugees into the country ‘could upset the very precarious balance between secularism and religion in Bangladeshi politics’, say, experts. Some Bangladesh-based Islamic movements called for the liberation of Rakhine and have threatened to wage ‘jihad’ on Myanmar ‘if the army and its associates do not stop torturing the Rohingya Muslims, because of the movements’ the intervention of the crisis country’s liberalism is under threats and a fanatic religious sentiment constantly taking precedence in the national body politics.

Rohingyas are found to be a potential national security threat in the subcontinent as it maintains a terrorist tie with the existing terrorist groups across the globe. On July 3, 2019, the Indian government told its Supreme Court that its intelligent inputs of links between some Rohingya Muslims and Pakistan’s terror group ISI and Syria based IS. The country’s affidavits reveal that ‘there is an organised network of touts operating in Myanmar and also West Bengal and Tripura states of India to facilitate the influx of illegal Rohingya refugees’.

The Criminal Investigating Department in Bangladesh arrested eight employees of 4 NGOs in charge of instigating the refugees in November 2018. All the members of the NGO, Small Kindness of Bangladesh that has channelled BTD 7.3 million funds from the Middle East, were found to have a link with now banned militant outfit Ansar Al-Islam.

CID and Counterterrorism and Transactional Crime unit (CTTC) found the other three NGOs such as Bangladesh Chashi Kalyan Samity, Nobo Krishi Private Ltd and Nobodhara Kalyan Foundation to be spending funds on and in instigating terrorism in Rohingya Camps. Owing to suspicious activities the Bangladesh government had to halt 41 NGOs’ operations in the camps on September 1, 2019.

Another report from October 11, 2017, a national daily reports that the government of Bangladesh banned 3 more NGOs from carrying out their relief operation in the refugee camps for misusing funds into luring religious-minded poor Rohingya refugees into militancy and other subversive activities.

National and transnational sex trafficking of Rohingyas women and girls takes place frequently by coercion, false marriage proposal, and abduction by local criminal networks. This trafficking has created sex tourism for foreigners and locals in Cox’s Bazar area risking the area vulnerable to sex-related crimes and exploitation.

37 Rohingya Muslims were found on a Malaysian beach, 22 Rohingyas were rescued from human traffickers in Teknaf and Maheshkhali sub-districts on May 12, 2019. Three Rohingya men were arrested with locally made weapons by Bangladeshi law enforcement personnel on July 9, 2019. A local Awami Jobo League leader Omar Faruk was allegedly shot dead by some Rohingya men on August 24, 2019. Rohingya men are found to be involved in abducting, and killing people from the host community. A cow tender has been killed on 19, February 2022.

The social, political and economic tensions between Rohingyas and the host community is intensifying every day. A local group demanding ‘Boycott Rohingya’ is gaining ground as locals are running out of patience.

In January this year, the Saudi authorities deported 13 Rohingyas who travelled to the Kingdom with Bangladeshi passports, while it is common knowledge that Rohingyas procure Bangladeshi passports through brokers and travel agencies with hefty money and bribes to the concerned officials.

A German-based Rohingya activist, Nay San Lwin, disclosed that “there are more than 1,000 Rohingyas languishing in the kingdom’s prisons for violating immigration rules and overstaying. He also revealed how Rohingyas secure their passport of different countries through smugglers which have been going on since the 1980s.”

Many Rohingya men and women were arrested by police in many different parts of the country after they sneaked out of the camps while dozens more were detained trying to go abroad after procuring Bangladeshi passports. Because of their involvement in various misdeeds and criminal activities the overseas labour market has been negatively influenced recently.

To worsen the situation, a few Rohingya drug pedlers attacked two members of the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) on December 30 leaving them critically injured. The RAB-7 Batallion of Chittagong arrested 12 Rohingya men with 3,96,000 pieces of Yaba pills on September 29, 2021, worth 120 million BDT. On September 29, 2021, Rohingya men shot dead Mohib Ullah, chairman of the Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace and Human Rights, who went to meet the former US President Donald Trump as an ambassador of the Rohingya minority of Myanmar in 2019. A Rohingya foreman died in a shoot-out between two Rohingya factions, in August 2022.

To look back, in 1998 militias from RSO took hostage of the refugee camp at Nayapara of Teknaf sub-district which claimed three in a clash with Myanmar security forces. A clash with local law enforcement personnel sent 64 Rohingyas in the same year. An investigative report found that some previously existing Rohingya camps were run by Harkal-ul-Jihad-i-Islam (HUJI). On February 21 this year, a group of Rohingya attacked 6 people including 3 German journalists snatching valuables. 22 have already been killed due to internal supremacy between factional groups. 68 narcotic-related cases, cases of rape, robbery and pretty crimes undermining the peaceful environment of the host country.

Since the latest influx, 328 cases have been filed against 71 Rohingyas. Survival sex, sexual harassment, increased demand of prostitution, sex trafficking, human trafficking, drug trafficking, host community’s demand for Rohingya child brides, child exploitation, vulnerability to terrorism, extortionists and supply house helps to nearby cities including Chittagong via smugglers are the contributing factors of enormous security threats to the country.

Suspected Rohingya men, who shot two BGB men, died in a gun-fight with police in November, this year. Rohingya men are held with firearms in the camp in the wake of 2021. A local online-based news site reported a local youth to be killed by a Rohingya man. A national daily reported that the entire education system in the district is under threat.

A drive conducted to Rohingya camps by a local magistrate of the district in early September this year. A huge number of locally made sharp weapons were recovered from a godown of an NGO named SHED. This is not the first time that Rohingya people are caught with their evil plan against their host country. Instigated by some NGOs they are ever ready to exploit the local community. While it quite a feat to avail a passport for a local Bangladeshi, Rohingya people are managing it without any hassle through a local Rohingya syndicate.

A finding by Iffat Idris, GSDRC, the University of Birmingham titled ‘Rohingya refugee crisis: impact on Bangladeshi politics’ cites a USAID risk assessment on Rohingyas in Bangladesh. It says, “The plight of both Rohingya and Bihari refugee communities in Bangladesh – denied citizenship rights and facing persecution – could make them susceptible to recruitment by extremist groups, militant groups related to Jamaat-e Islami have been actively recruiting from Rohingya refugees in the past, and are doing so in the context of the current refugee influx”.

It also warns that “As the Rohingya crisis continues to deepen, Bangladesh will become ever more attractive to an array of Islamist militant groups seeking to recruit the hapless victims of the Burmese government’.

Bangladesh Institute of Peace and Security Studies’ Especial Report outlines that, “The Rohingya refugees who are completely marginalized are most vulnerable to human trafficking. It has been reported that international human trafficking gangs are actively looking at this situation to exploit the vulnerability of the Rohingya for profiteering, food security will be hampered as the country will likely to face food shortages and price hiking of essentials because of the influx, the labour market will be unstable for locals because of increased demands, internal security will face threats as the refugees get out of the camps and mingle with local people in the vicinity and beyond, transnational security will be jeopardised through arms and drug trafficking”.

Utpala Rahman in “The Rohingya Refugee: A Security Dilemma for Bangladesh’ puts that the way to prevent long-term encampment of refugees and militarisation of Rohingya camps is to ‘make the Rohingya community workable by uplifting them educationally, socioeconomically and politically. He calls for a refugee law that gives the Rohingyas work permits and even short-term dual citizenship. But given the much bigger numbers of Rohingya entering Bangladesh in the current wave, and the sensitivities around allowing refugees to integrate with the local population, it is unlikely the government will follow this course.

Environmental disaster

With elephants roaming around the site of Balukhali-Kutupalong was a pristine forest with vibrant biodiversity just a year ago where the world’s largest refugee camps have been sprung by indiscriminate cutting of hills as the Rohingya crisis in Bangladesh began. As fuel has become one of the most essential non-food items constant felling of trees has become the primary source of fuelwood. The quantity and quality of toilets have been a concern of environmental issue. Human, plastic and other types of wastes management have become an unavoidable fact of contention for the host communities, too.

The camps are overcrowded with people. The average useable space for a person is 10.7 square metres whereas the internationally recommended standard of averaged habitable space for the refugee is 45 square metres per person and cannot be lowered than 30 square metres per person. The camps sprang up with no regard to biodiversity and deforestation and its subsequent adverse outcomes.

A total of 4300 acres of hills and forests have been made habitable for the infrastructure and temporary shelters. Apart from housing facilities, the camps need nearly 6800 tons of fuelwood every month while every Rohingya family everyday uses 60 bamboos. Lack of food was one of the most common complaints among refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch. The need for food is also inextricably linked to the need for cooking fuel. So far, the fuel most commonly used in the camps for cooking is firewood. Even when families have enough food, a lack of fuel can make it impossible to cook the rice and lentils they receive as rations.

A joint study conducted by, The Rapid Environmental Assessment Study was initiated by the Ministry of Environment and Forest (MoEF) of Bangladesh and by UNDP and UN Women to assess the environmental impacts of the Rohingya influx into Bangladesh addresses environmental and related gender-based issues and health risks.

Eleven environmental impacts were identified that have been or could potentially be exacerbated by the Rohingya influx. Six of these were physical environmental impacts on ground-water; surface water; acoustic levels; indoor air quality; solid waste management; and soils and terrain; and the remaining five were impacts on ecosystems: natural forests; protected areas and critical habitats; vegetation; wildlife; and marine and freshwater ecosystem.

The following risks associated with the physical environmental impacts were assessed as high: groundwater depletion; groundwater contamination; poor indoor air quality; poor management of sewer sludge; removal of soils and terrain; and changes in terrain. Impacts on ecosystems with high associated risks were: deforestation and forest degradation; encroachment onto and resource extraction from protected areas; changes in land cover; rapid biomass reduction; loss of species; loss of wildlife habitat and shrinkage of wildlife corridor; and mortality risks for wildlife.

The study identified the following gender-based issues: the health risks of inhaling smoke from cooking inside poorly ventilated shelters; the physical demands of firewood collection; and a lack of separate bathing and toilet facilities for women. Overuse of natural resources such as the unregulated collection of firewood and the extraction of the groundwater may give rise to conflicts between the Rohingya and the host communities, which could disproportionally affect women as one of the most vulnerable groups of the population.

With the significant rise of social conflicts between shoe communities and Rohingyas over the use of forest resources, according to UNDP assessment, the Rohingya influx influenced 26,000 hectors of the total 60,000 hector of forest land in Cox’s Bazar which will be degraded and converted into shrub-dominated areas with low biomass and productivity if the collection if fuelwood from the forest continues. It will also found a substantial impact if the proposed Inanai National Park and Himchari National Park.

Groundwater depletion and contamination as one of the 18 key risks identified by the UN body owing to the Rohingya crisis.

The health conundrum

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) or Doctors Without Borders, is an international humanitarian medical non-governmental organisation (NGO), reports that from August 2017 to March 2019 they have carried out consultations to more than 1,242,500 outpatient and 21,549 inpatients. The most common diseases were respiratory infection, diarrhoea and skin diseases, although they report on providing healthcare to 7032 diphtheria patients, 4987 micelles and 99,681 diarrhoea patients. The health-related issues are exacerbating among the host community because of the Rohingya crisis in Bangladesh.

The aggravating circumstances of geography and climate, refugees living in the close vicinity are at heightened risk of communicable diseases, fires, and community tension, domestic and sexual violence. According to WHO, 1.3 million people need health assistance worth of $113.2 million and approximately 60, 000 women are estimated to be pregnant, adding woes to the one million-plus Rohingya population it welcomed 48,000 babies last year. Even though it is not possible to know the true pictures of babies born as a result of sexual violence, UNICEF says more than 60 babies are born every day in the camps.

A total of 8,640 diphtheria case patients have been reported in the Early Warning, Alert and Response System Jun 2019, since the start of the outbreak.

More than 60 babies are born every day.

16 people have been diagnosed with AIDS so far in the Rohingya camps. According to UNAIDS Myanmar is one of the 35 countries witnessing 90 per cent of HIV infection globally. 7,800 people have already died of HIV while 2,30000 people are living with HIV. Rohingyas are not excluded. An Upazila health and family planning officer from a Sub-district health centre expressed his concern over HIV, “We never know how many Rohingya people are infected and entered Bangladesh”.

The powerful gainers of the game

Displacing Rohingyas from their ancestral homes might sound like merely majority persecution of minority Rohingya Muslims. Politically they have been in systematic victimisation of the state in seeking economic prosperity at the cost of Rohingyas. Why the majority Buddhist government of Myanmar came to decide stripping Rohingyas of citizenship in 1982 might be because of the Muslim minority’s disloyalty towards the kingdom during its independence struggle. It presented them as untrustworthy outsiders alongside the fear of Islamisation of the state which provided a potent ideological fuel for the exclusion of Rohingyas from the majority Buddhist body politics.

The political will of the International Community is still vague regarding the repatriation of Rohingyas from Bangladesh and prosecution of the army generals responsible for the monstrosities. France continues investment in the country even after its admission of ‘genocide’ committed by the Myanmar government. India and Russia do not bother to stand beside Myanmar regardless of the atrocities committed.

As Rohingyas now have been driven out of the country, the de facto ruler Aung San Suu Kyi and its army chief are in a peaceful state entertaining no prospect of having them returned anytime soon. Political action that Myanmar has taken refuge in speaks volumes while the three countries’ –India, China, and Russia— landing their support made repatriation even harder. China and India are competing over a common cause of influencing Myanmar. Myanmar’s procurement of military from Russia undoubtedly an important role in its backing toward Myanmar.

Pakistan has been a silent spectator. The United States is caught between a hard and a rock place between its ‘Asia Pivot’ and powerful economic rivals– China and Russia–while India and China teaming up to US economic intervention in Asia.

India’s support of Myanmar is obvious, while at the same time it fears whether the refugees could travel to India to make the country’s security state volatile. Like China, India is also eyeing at the development of economic relations with Myanmar via Indian founded Keladan multi-model project which will help it reach Sittwe port. Analysts analyses that India is also capitalising on the current Rohingya crisis to improve its transnational relations with Myanmar.

Conclusive perspective: Rohingya crisis in Bangladesh

There is a long-standing debate about whether Rohingyas are Bengalis or Burmese by nationality, there are insurgent awakening attacks on Myanmar’s state forces, there are state-sponsored retaliatory atrocities on helpless the Muslim minority, there is also no undenying fact that Rohingyas are actually Bengalis from the historical perspective who migrated in the then Arakan state for various reasons ranging from labour export, vast resourceful land property acquisition, there is a political and economic interest that requires the evacuation of the state in order to incur economic momentum and there is also victimisation of the innocents by political quarter who capitalise religion in agitation.

It is also equally true that the current Rohingya crisis is simply not a stand by the Myanmar government against Muslims because if that is the, then its ultimate purpose would have been to drive the entire Muslim community that has spread across the country. It is also true that Myanmar cannot just get rid of Rakhine Muslims who have been living in the region for generations just because it wants it. Its part in cleansing an entire ethnic minority does not justify Myanmar’s economic greed which is being taken root in the state at the cost of humanity.

Myanmar’s attitude in driving out Rohingya Muslims sounds anonymous to throwing the baby with the bathwater in the pretext of rooting out terrorism while it singlehandedly deal with the terrorists according to law and order on the country.

Regardless of multiple viewpoints to perceive the current refugee crisis in Bangladesh considering the possible security, economic, environmental, health, food, and livelihood it is imperative that Myanmar should come forward in a peaceful dealing in the Rohingya crisis.

It seems like the neighbouring countries of Bangladesh are taking advantage of Bangladesh. Pakistan is so ever ready to see Bangladesh’s downfall. Politically Pakistan did not like an independent Bangladesh and a section of political supporters who still ideologically dream of a Pakistan model of Bangladesh remains active. India is gearing up its citizenship law through the BJP’s hands in order to deport foreigners, who are predominantly Muslims, from Assam and West Bengal. The nationalists see them as Bengalis from Bangladesh.

Already burdened with a 163 million population with high unemployment and frequent natural disasters Bangladesh has been victimised on humanitarian grounds. Bangladesh awaits a server time ahead. Religion and international politics are at their core. Rohingyas will never be able to go back to their home unless Myanmar changes its citizenship policy which who knows when will take place! Not anytime soon, of course.

While the burden of dealing with this mass influx has mostly fallen on Bangladesh, the responsibility for the crisis lies with Myanmar. Even though they want to return to their home country the conditions of their well-informed voluntary decision-making, recognition of their citizenship with equal citizenry rights, justice for the crime committed against them, the return of their property and assurance of security remain as primary objectives. Sensing the possibility of not meeting the demands by the Myanmar government laid by Rohingyas and the NGOs active in the camps, another repatriation plan was thwarted by Rohingyas on August 22, 2019, as no one showed up to be repatriated.

In the meantime, donor governments and inter-governmental organizations should be genuinely and robustly involved, both in supporting Bangladesh to meet the humanitarian needs of all Rohingya refugees of the crisis – particularly by funding the humanitarian appeal for the Rohingya humanitarian crisis – but also by applying concerted and persistent pressure on Myanmar to meet all conditions necessary for safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya refugees.

It is truly shocking to hear of Solidarity Compact, the international organisations have come up with. Like Jordan, Lebanon and Ethiopia, Bangladesh will have to abide by the compact as a host country as to it should keep the refugees in exchange for facilities like duty-free market access its products in the international market, migration of the country’s labour force and foreign direct investment (FDI) into the country. Is that really so?