Last updated on June 27th, 2024 at 01:59 pm

Healthcare costs and medical negligence in Bangladesh are extremely inhuman events that the poor section of people cannot suffer. Before diving into the main objective, let us get to know about a true story regarding the ordeal and heroic acts of a poor labourer, Manji, from a far-flung village in Bihar state of India who has been lauded for his strenuous efforts for making healthcare accessible to the distant section of the people in his state. The 2015 Bollywood film, Manji-the Mountain-man was indeed inspired by his life.

The film perfectly illustrates of hardship and difficulties faced by people in need of medical and healthcare facilities. The protagonist of the film, Dashrath Manjhi, commonly known as the “mountain man” and a daily labourer by profession, took the job of breaking the stony mountain to create a road, after his wife’s death, so people can easily go to healthcare facilities, in Gehlaur village in Bihar of India.

His wife died on the way to the hospital while being carried through the rocky and mountainous path. Devastated by her death of lack of treatment, Manji determined to carve a path through the rocky mountain for the people who had either climbed across or travelled around in order to gain medical services at the nearest town Wazirganj.

Through his unwavering determination and endurance and hard work and after 22 years he successfully made his dream come true. He was able to make a 30-foot-wide and 360-foot-long path through a 25-foot-tall hill. Without any modern machinery and labour force, Dashrath’s breakthrough came through simply a hammer and chisel. There is a road now using which people easily go and get healthcare. Dashrath Manjhi died in 20017.

But with the advent of massive urbanisation, modern medical facilities, more healthcare facilities at the doorsteps, more doctors and faster means of communication, how beneficial is the current healthcare facilities for the poor or the lower-middle-class people? How affordable is it for us? Who are the biggest beneficiaries, the poor or the capitalists? Are the people who can’t afford it supposed to die of negligence? The following incidents tell volumes regarding the affordability of healthcare and the negligences carried out by medical professionals.

After 11 years of Dashrath Manjhi’s death, another Manjhi carried the dead body of his wife from Bhawanipantha town of Orissa to his village which was 69 miles away from the hospital in the town. Impoverished, failing to obtain an ambulance from the hospital and unable to hire a private one he decided to carry the dead body of his wife accompanied by his 12-year-old daughter.

After walking 12 miles in a scorching hit he gets help from locals. A father carried his dead son’s body as the doctors denied him the services of an ambulance by the hospital to carry the body to his native village in Etawah. A man carried his mother’s dead body in Jalpaiguri of West Bengal as the Ambulance demanded 3000 rupees.

Healthcare costs and medical negligence in Bangladesh

Unable to pay hefty hospital bills a daily labourer and his wife fled from the hospital leaving the newborn baby in the hospital, on September 28, 2018, in the Comilla district of Bangladesh.

Even though the family of the deceased agreed to pay 12, 000, 00 of 31, 000, 00 of the medical bill the hospital authority refused to release the dead body to the family until the High Court of the country intervened. The report says a hospital in the capital city of Bangladesh extorted a family by keeping the dead body of their newborn baby in the ICU for days.

The survivors of the Rana Plaza disaster that killed nearly 2000 garment workers are held hostage at Enam Medical College Hospital, which came forward with assistance for the victims. Failing to pay the hefty medical bill of TK. 12, 000, 00 the mother and newborn were baby kept in the hospital rooms for months. Paying TK. 7, 000, 00 from debt and selling land property could not help them get the baby released.

A young businessman dies of a lack of treatment in the Lalmonirhat district. Abbas Ali, a resident of Dhowlatpur of Khustiya did not get treatment even after visiting two public hospitals in his locality. The hospitals sent him back without treatment as he was unable to pay the direct medical cost of a heart operation.

Two patients died of failing to be treated at UHC (Union Health Complex) of the sub-district of Nilfamari last year. Relatives of the deceased claimed that there were no on-duty doctors during the patients were rushed to the hospital. A newborn died of lack of treatment after delivery. The patient died because he was unable to bribe the medical professionals to get admitted.

A teenage girl was allegedly killed because of professional negligence by on-duty doctors. The allegation came from the family of the baby that the on-duty doctor was busy Facebooking while the baby was admitted to the hospital. Due to wrong treatment, a child lost one of his scrotums. A national daily in Bangladesh published news of how healthcare-seeking people are made hostage in the hands of medical professionals and doctors. The news talks about how people from lower income sections are deprived of their right to have healthcare which they have to buy at a fee ranging from BTD 500 to 1000.

These are the only published news in print media. Many incidents like these remain unpublished, unnoticed, or cover-up many times as they take place in undeveloped, underdeveloped localities in Bangladesh due to political or religious reasons.

Today, in the 21st century people may not have to climb the rocky mountains or travel a considerable distance to avail medical care like Dashrath Manjhi. Roads are built, communication is developed, poverty has been reduced by 36% since 1990 and the world aims to eradicate poverty by 2030, awareness and education multiplied manifold.

But questions of the Right to Health and punishment for the injustice done to the victims of medical negligence by medical professionals are still a far cry for the poor population across the world, especially in Bangladesh. People have to sell their valuables or raise public funds or beg for money to avail medical care. Without money, a sick person has no right to live and get treated.

Health right

The WHO defined universal health coverage or UHC as ‘access to key promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative health interventions for all at an affordable cost, thereby achieving equity in access. All countries, at all stages of development, can take immediate steps to move towards universal health coverage”.1

Healing is a matter of time, but it is sometimes also a matter of opportunity.

-Hippocrates, Greek physician

Health is universally regarded as an important indicator of human development. Whether ill health is both the cause and effect of poverty, illiteracy and ignorance or poverty is both cause and effect of ill health, illiteracy and ignorance are still be decided. Policies of human development not only increase the income of the population of a country but also improve other elements of their standard of living, such as life expectancy, health, literacy, knowledge and control over their destiny. Health is both a major conduit to human development and an end product of it. Better health is a primary objective because it helps bring out human potential, creativity and physical capabilities.

Poverty in Bangladesh is a vital block to a way forward in access to health in terms of status and services and health is a crucial mediator between poverty and reproductive choice.2

A researcher from the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology University, Gujarat writes, “Health has importance in three distinct ways: (a) intrinsic importance, (b) instrumental importance at personal and social levels, and (c) empowerment importance. In an intrinsic sense, health is important, because it is a direct measure of human well-being. It is a fulfilment of life and a valuable achievement in itself.

In the instrumental sense, better health is important in many ways. For example, good health has an economic rationale. Better health reduces medical costs, both, of the government and of the households. In the case of children, better health leads to better attendance in schools and to higher levels of knowledge attainment. Better education and knowledge lead to better-paid jobs and larger benefits to the future generation. For women, better health status is achieved through empowerment. But, it also empowers them to participate in economic and public life”.3

World Health Organisation (WHO)4 affirms that the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is a fundamental human right (preamble). The right to health is an inclusive right. The right to health extends further to include a wide range of factors that can help us lead a healthy life. Internationally, it was first articulated in the 1946 Constitution of the World Health Organization (WHO), whose preamble defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”.

WHO further says, “The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition underlying determinants of health”. According to WHO,

1. “The right to health contains freedoms that include the right to be free from non-consensual medical treatment, such as medical experiments and research or forced sterilization, and to be free from torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

2. The right to health contains entitlements that involve:

- a) The right to a system of health protection providing equality of opportunity for everyone to enjoy the highest attainable level of health;

- b) The right to prevention, treatment and control of diseases;

- c) Access to essential medicines;

- d) Maternal, child and reproductive health;

- e) Equal and timely access to basic health services;

- f) The provision of health-related education and information;

- g) Participation of the population in health-related decision-making at the national and community levels.

3. Health services, goods and facilities must be provided to all without any discrimination. Non-discrimination is a key principle in human rights and is crucial to the enjoyment of the right to the highest attainable standard of health (see the section on non-discrimination below).

4. All services, goods and facilities must be available, accessible, acceptable and of good quality.

5. Functioning public health and healthcare facilities, goods and services must be available in sufficient quantity within a State.

6. They must be accessible physically (in safe reach for all sections of the population, including children, adolescents, older persons, persons with disabilities and other vulnerable groups) as well as financially and on the basis of non-discrimination. Accessibility also implies the right to seek, receive and impart health-related information in an accessible format (for all, including persons with disabilities), but does not impair the right to have personal health data treated confidentially.

7. The facilities, goods and services should also respect medical ethics, and be gender-sensitive and culturally appropriate. In other words, they should be medically and culturally acceptable.

8. Finally, they must be scientifically and medically appropriate and of good quality. This requires, in particular, trained health professionals, scientifically approved and unexpired drugs and hospital equipment, adequate sanitation and safe drinking water.

Healthcare costs

Though, since its independence Bangladesh has made remarkable progress in ensuring healthcare facilities for everyone, especially for the poor. Hundreds of thousands of women and children in rural areas and people from the poorer strata, including those living in urban slums, have neither the “goods” to maintain health, nor access to services that could decrease the severity of their illness. Getting qualitative healthcare, rapid recovery from illness without losing one’s ability to earn bread, and paying the exorbitant price is as uncertain as falling ill.

So, to speak about the current state of healthcare, “Non-availability of drugs and commodities, discrimination against poor, imposition of unofficial fees, lack of trained providers, weak referral mechanism, unfavourable opening hours and interdepartmental difficulties contribute to low use of public facilities in Bangladesh. Providers available in the system are also inequitably distributed between urban and rural areas, with rural facilities experiencing vacancies afflict the health sector of the country”.1 Poor and financially weak patients are to bear the brunt.

According to the Public Expenditure Review of the Health Sector by the Health Economics Unit Bangladesh, the health expenditure in 2020 was BDT 777 billion accounting for 2.8% of GDP. In the same year government spending on health was BDT 179.74 billion representing 23% of the health expenditure, 0.66% of GDP. The review shows how out-of-pocket health expenditures of each household e rose from 64% to 74% in the year 2020.

Transparency International Bangladesh’s findings say that hospitals and diagnostic centres of the country into, “excessive profit-seeking businesses, commission-based marketing mechanism” where everyone- from physicians to receptionists- benefits from the widespread malpractice.

Due to low government spending on healthcare, 15% of people were not treated due to their inability to pay for the high cost of healthcare. The high amount of personal spending leads poor people to beg for money to treat themselves or a slow but untimely death. However, it is the poor section of people of society who have to take the burdensome cost of healthcare.

The healthcare costs in the country can be divided into direct medical costs (e.g. medicines and service fees), direct non-medical costs (e.g. transportation costs) and indirect costs (e.g. travelling and waiting time, lost earnings). The available evidence shows that the cost of medicines was the most important cost element that prevented people from using health services.2

15% of the people in Bangladesh were not treated due to their inability to pay for the high cost of healthcare

Indirect costs are the monetary value of productive time losses to the patient and other family members as a result of the illness. Indirect costs of treatment for illness were also higher for public hospital patients except for medicine, chest medicine, orthopaedics, and rheumatology departments compared to private hospital patients.

Direct costs include medical and non-medical costs; medical costs include diagnosis, registration fees, medications, diagnostics, continuing care, hospitalization, and rehabilitation; and non-medical costs are the costs of transport to the hospital and any informal payments. Informal payments are defined as a money transfer from a patient to hospital staff with the expectation of quick or better treatment. The direct costs of treatment for illness were higher in all hospital departments in public hospitals than in private hospitals except for surgery, gynaecology, and orthopaedics.5

Equally, Available evidence suggests that poor governance in the health sector is obstructing the healthcare service delivery mechanism in Bangladesh, which, in turn, results in low utilisation of public facilities. Non-availability of drugs and commodities, discrimination against the poor, imposition of unofficial fees, lack of trained providers, weak referral, feedback and monitoring systems, unfavourable opening hours and interdepartmental difficulties contribute to the low use of public facilities in Bangladesh.

The rising indirect healthcare costs in public hospital patients are primarily explained by high travel and long waiting times, especially compared to private hospital patients. Public hospitals patients spend on average almost double the time accessing treatment which includes travel time and waiting time at the hospital to see a doctor. This indicates that public hospital patients spend approximately double the time compared to private hospital patients. Most public hospital patients (71 %) were coming from rural areas and their travel time and cost is higher than that of patients who visited private hospitals who mainly resided in the city.

In the public hospital, the numbers of doctors were insufficient and there were always long queues for treatment observed. Some of the public hospital patients tried to jump the queue by offering bribes to staff in an attempt to get to see the doctor more quickly. In a public hospital, 114 out of 139 patients (82 %) paid money as informal payments to see the doctor earlier. On the contrary, only 44 out of 113 patients (38 %) paid money as informal payments to private hospitals.

The public hospital quality of care was considered inferior compared to private hospitals due to the lack of an efficient and effective operating environment in public hospitals. This was manifested through informal payments, long waiting times and staff indifference and negligence.5

There may be several reasons why poor people use public healthcare facilities. First, poor people are likely to be especially vulnerable to illness because of a lack of proper diet and the generally unhygienic conditions in which they live.

Second, low levels of education and income, and high levels of malnutrition and undernutrition may result not only in higher actual morbidity for the poorest strata but also in a higher level of utilisation of public facilities.

Third, when fall ick poor people have no choice but going to public hospitals for being comparatively cheap while the rich patients might choose private or more qualified doctors where time is spent less. This trend of availing better healthcare culture by the rich people make them have preferential treatment as if they are entitled by the state for this discriminatory treatment.

As per the subjects of the study, in the public health facilities, only 23.9 per cent of the outpatients received all the medicines prescribed, the corresponding figure for inpatients was even less, only 7 per cent. Similarly, another research found that about three-fifths (62 per cent) of the inpatients and 48.3 per cent of the outpatients received less than 50 per cent of their required medicine from the hospital.

Again, 14 per cent of inpatients and 8 per cent of outpatients did not receive any medicine at all from the hospitals. The situation was even worse with respect to injectable/IV fluids. More than half of the inpatients (54 per cent) did not receive any injectable from the hospital, while two-thirds of them (66 per cent) did not receive any IV fluids.2

For out-patients and in-patients, “The cost of health care often results in foregone medical treatment. The cost of medicine, various charges associated with tests/investigations and the cost of hospitalisation are some of the most important barriers to health services utilisation. Extremely poor households spend more than one-third of their household income on healthcare expenses.

Rising healthcare costs: how much is too much?

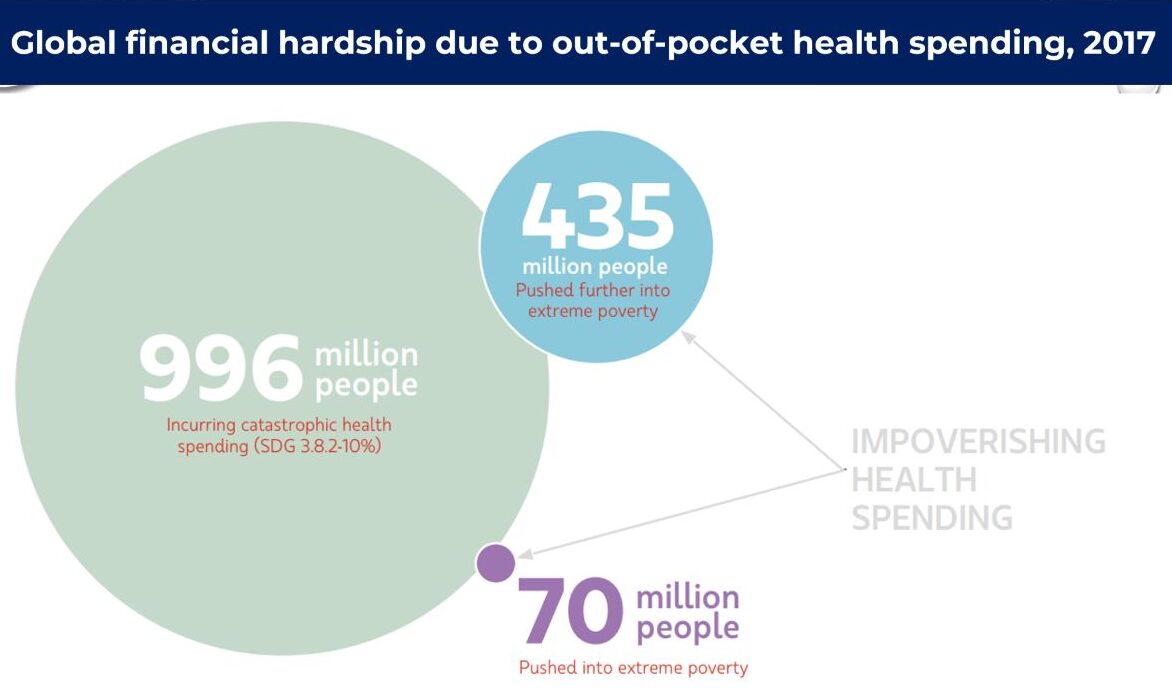

According to the World Bank, 10 % of the world’s population still lives on USD 1.90 per day, while more than 1 billion people live in extreme poverty that does not have access to essential health services. Around 6% of the population of world still lacks proper health care.

In Bangladesh, as in most developing countries, a barrier to public health facilities forces the poor to pay for healthcare out-of-pocket, often driving them further into poverty. Medical care in the country is very costly relative to an average person’s mean family income, often difficult to access and leaves a household vulnerable to the effect of catastrophic health expenses.6

As such according to the Bangladesh National Health Account, out-of-pocket (OOP) health expenditure (private expending) is 67 % which is more than the global average of 32 per cent. “After OOP, the second-largest contributor is the government while the rest follow from the private firms and development partners such as NGO’s ranging from 1% to 2%. Moreover, household expenditures as a percentage of GDP increased from 1.6% to around 20% in 2010”.

Around 6.4 million or 4 % of people in Bangladesh get poorer every year due to excessive health costs. The poorest 20% of the population spent 16.5 % of their household income on direct health care costs, while the richest 20 % spent just 9.2 5%.

Because of excessive OOP, health shocks can happen which can be catastrophic for individuals, which can also trap the vulnerable households indefinitely into poverty cycles, which is a matter of great concern from a public policy perspective.

According to a study, “About 40% of the families reported a loss of working days due to illness in a given year. Loss of savings or capital combined with the inadequacy of social security schemes in developing countries, the poor people are often forced into deeper poverty (and the low-income non-poor into poverty) by their limited ability to cope. Of the 3,941 households (comprising of 19,424 individuals) reported 1,457 having missed work over the preceding 12 months due to illness. Of this group, 462 cases involved loss of up to 5 working days, while 219 remained absent for more than 31 days.

Altogether 1,186 illness episodes can be classified as ‘health shocks’ over 2 years, where a shock is defined to involve a certain threshold in terms of either expenditure or duration of illness. The poor and the children are the most deprived section.1

Out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure in Bangladesh is 74%, whereas according to the Word Bank, the global OOP spending is 18.1%

Research says, “Out-of-pocket expenditure for healthcare continues to be the most significant issue in the developing world. A sudden serious feature of the illness deceits in the critical susceptibility of the poor to unexpected and unforeseen healthcare-related vulnerabilities increased indebtedness due to income loss, and even unemployment.

High out-of-pocket expenditure in purchasing pharmaceuticals is the most distinctive feature in Bangladesh. 65% of the healthcare expenditure is on purchasing drugs and medical consultation”. “Other components of OPP are services of curative care (22.00%), ancillary services (9.0 %) out-patient and home-based services (4%) and general government administration of health less than (1.0%).7

Out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure is significantly expensive as 25.5% of the population of Bangladesh is still below the poverty level.8

A study conducted on 12,240 households reveals that “The consequences of excess OOP expending are enormous. Some households may not utilize formal healthcare at all due to excessive OOP payments that compel them to receive partial healthcare and which thus exacerbate the disease condition, causing the disease to become a chronic condition. Households may sell their movable and immovable properties to manage the treatment costs, which in turn make them poorer. Due to excess health expenditures, households may need to ration their food items, and thus may become malnourished. OOP health expenditure may affect education, causing children to drop out of school.7

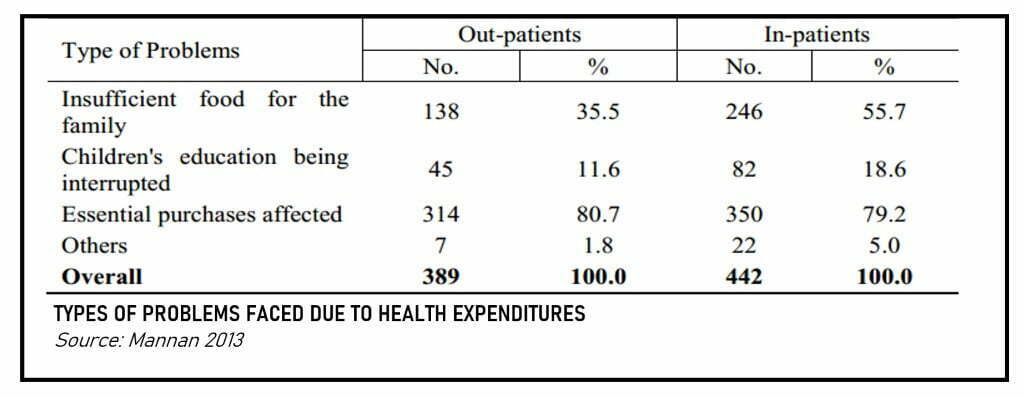

The poor section of the population has to finance their health care needs through various sources that include drawing from savings, borrowings from friends/moneylenders, and distress sale of assets/household articles. Even that may not be sufficient to buy the medicine in full. Findings show that expenditure on health resulted in the withholding of other subsistence resources (reduced food consumption, less expenditure on children’s education, etc.).

Overall, 18.6 per cent of households had to face problems in financing their children’s education. Thus, illness requiring treatment and hospitalisation has significant adverse implications for the economic well-being of affected households, particularly for the poor. Drawing from savings, borrowings from friends/moneylenders, and distress sale of assets/property can be the only refuge to access healthcare in the country.

This results primarily because, for the poorest groups of people, most of their income is spent on purchasing food and other daily necessities of life leaving very little to spend on health care.

Findings clearly indicate that members from poorer households have less access to resources available for health care and have to undergo a lot of economic pressure to finance their treatment costs/medical needs. The findings imply that for low-income households there is a real risk of indebtedness involving “catastrophic payments.” According to the researchers of the Public Health Foundation of India, out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure greater than 10 per cent of total household expenditure may be defined as catastrophic payments.9

Let alone the WHO proposed 15 % of the health budget of the total budget the government of Bangladesh has given a 5 % share of the budget to healthcare for the fiscal year of 2018-2019 which is smaller than the previous FY’s share of 5.39%. This uncalled for and inadequate amount of health budget accelerates the pressure on poor people.

The average OECD share for the health sector was 6% of total spending in 2017 with the United States’ highest share of 17.2% of GDP.

Unable to buy health service Report says, 75% of cancer patients either face financial catastrophe or die within a year of diagnosis.

The perceived need for medical care would depend both on the availability of healthcare facilities and the capacity to pay for health services. Hospitalisation that requires surgical interventions or prolonged stay in the facility ruins the families both economically and physically. They have to spend money on medication and they also lose their incomes – in some cases for months together, particularly in cases where the patient himself/herself is the earning member.

Out-Of-Pocket (OOP) health expenditures affect education causing drop out of school.

Excessive healthcare expenditure by the poor section of the people may negatively result in the supply of insufficient food for the family, and children’s education is affected as school fees are delayed and children are deprived of daily necessities. Food consumption had to reduce in the 57 % of the households who were already affected by excessive healthcare costs, expenditure had to be curtailed on other essential household items for another 79.2 per cent of cases because of the treatment cost.

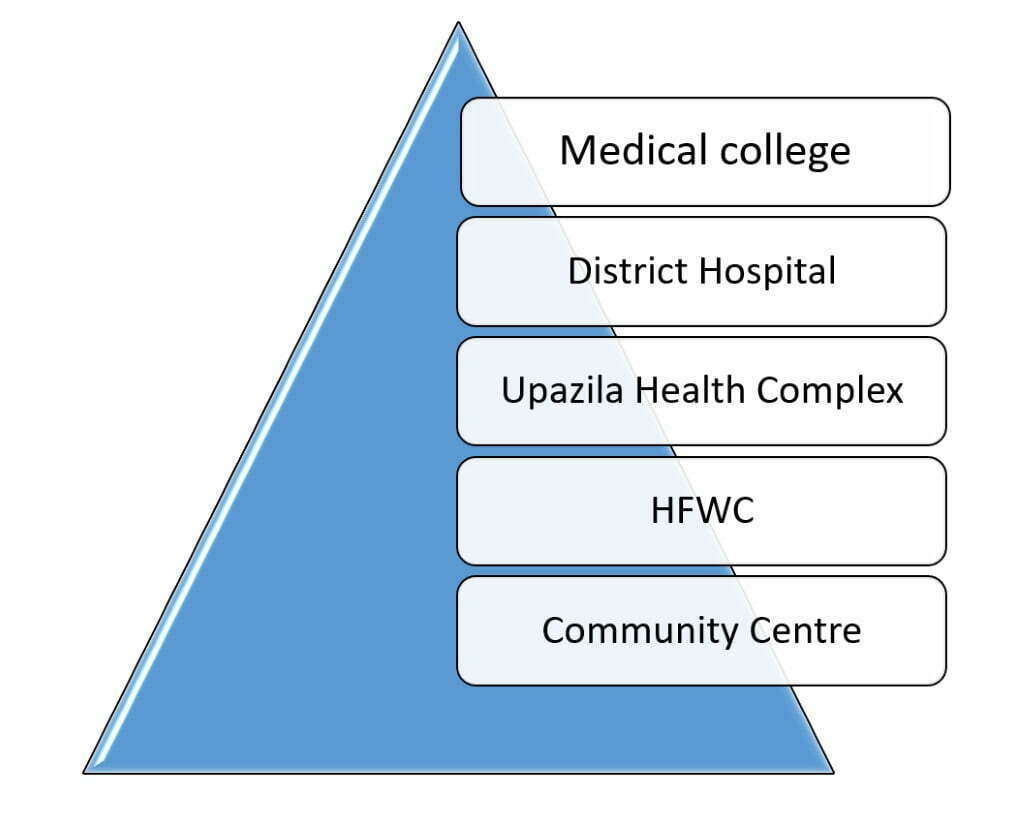

The country’s health system is hierarchically structured and can be compared to a five-layer pyramid:

First, at the base of the pyramid, there is the ward-level health facility (CC Community Clinic), consisting of a health assistant and a family welfare assistant.

Healthcare facilities in Bangladesh

At the second level is the union health and family welfare centre (HFWC-Health and family welfare centre) staffed by a medical assistant, one family welfare visitor and one pharmacist, which concentrates on the provision of maternal and child healthcare, and provides only limited curative care.

Third, there is the Upazila Health Complex (UHC) with nine doctors, two medical assistants, one pharmacist, and one radiographer and one EPI technician. The UHC is responsible for inpatient and outpatient care, maternal and child health services and disease control.

Fourth, the district hospital (DH-District Hospital) is the first layer of the health care pyramid to have theatre facilities, but some selected UHCs have also got EOC facilities.

Finally, medical colleges and post-graduate institutes form the top of the health services pyramid offering a wide range of speciality services.2

Effective Accessibility to healthcare includes a number of key dimensions:

(a) Physical Accessibility (distance, travel time and travel costs);

(b) Economic Accessibility (cost of medicine, cost of the consultation, cost of hospitalisation, cost incurred with respect to tests/investigations);

c) Social and cultural context (gender) affecting accessibility;

(d) Perceived quality of services:

– availability of doctors

– availability of medicine

– attitudes of doctors/nurses

Information accessibility, on the other hand, implies that people should have informed choice regarding the sources, types and quality of services. But patients visiting higher level facilities (district hospitals, teaching hospitals and specialised hospitals) have to wait much longer to see the doctor: waiting time was highest (82 minutes) for outpatients attending specialised hospitals, second highest (65 minutes) for teaching (medical college) hospitals, and lowest (58 minutes) at the district hospital.2

“Economic accessibility” means that health facilities, goods and services (drugs and other treatment-related items) must be affordable by all. Government facilities are the last resort for the hapless poor who cannot afford to consult a private qualified doctor. But evidence shows that even though health care services are supposed to be free at public facilities, patients have to bear the costs of medicine and laboratory tests, as well as some additional costs.

The average indirect cost analysis suggests that patients treated in public hospitals faced more income or productivity loss in each age quintile than that in private hospital patients.5

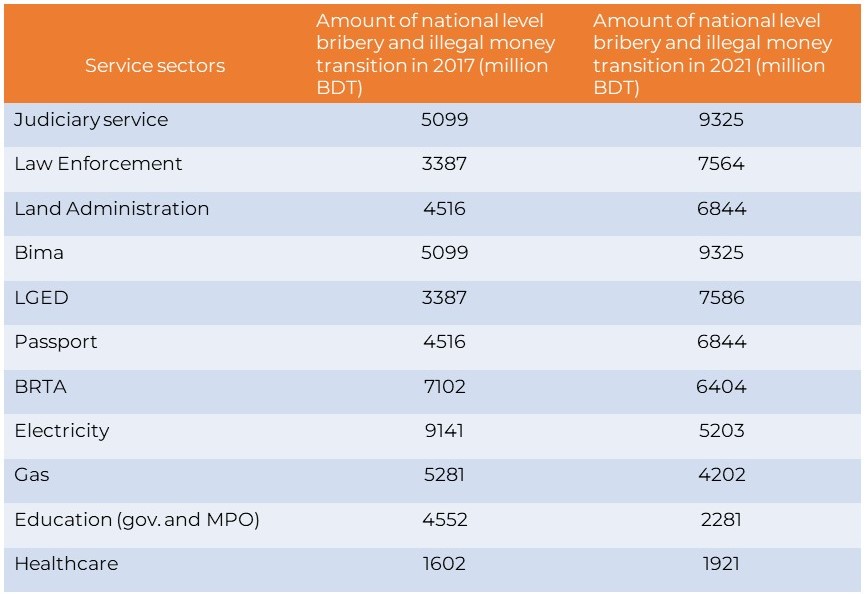

Corruption in the healthcare sector in Bangladesh

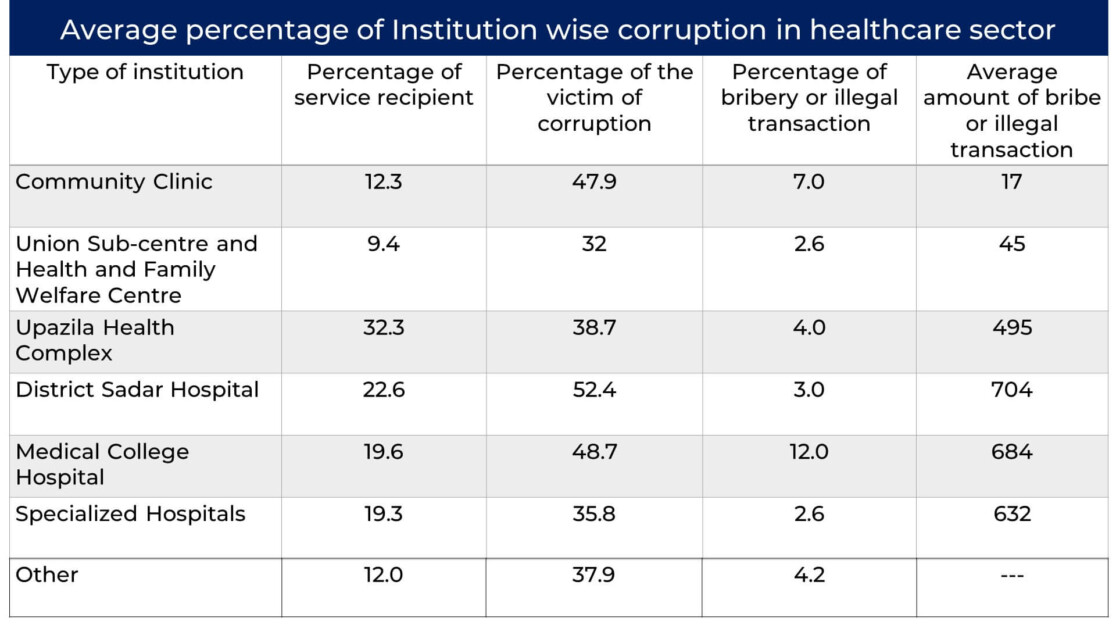

The objectives of the national health policy are to provide sustainable development to the health, nutrition and family welfare situation of the poor, marginal and ultra-poor of the country. At present, the government is providing these services through various institutions at the primary level (Community Clinic, Union Sub-centre, Union Health and Family Welfare Centres, Upazila Health Complex), secondary level (District Sadar Hospital) and at the tertiary level (Medical College Hospitals and Specialized Hospitals). Despite activating different programmes and achieving important successes irregularities and corruption still exist.10

The Constitution of Bangladesh provides Basic rights but not a special right to the patients. Article 15 (a) and 32 read – it shall be a fundamental responsibility of the state to attain, through planned economic growth, a constant increase of productive forces and a steady improvement in the material and cultural standard of living of the people, with a view to securing to its citizens- (a) the provision of the basic necessities of life, including food, clothing shelter, education and medical care. (b) No person shall be deprived of life or personal liberty save in accordance with the law.

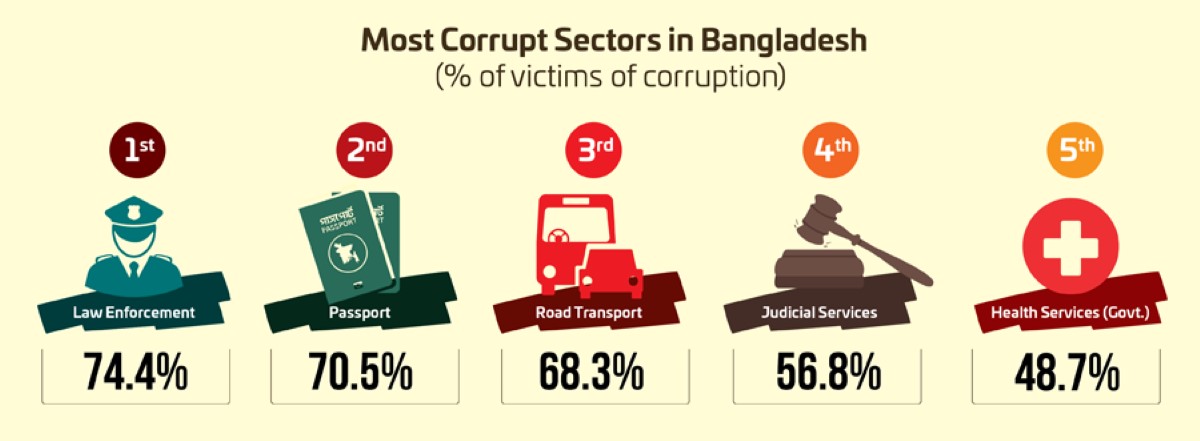

Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB) reports that the Health Sector in Bangladesh is the 7th computed sector. Overall 70.9% of, which was 66.5% in 2015, corruption impacted the households in the country, while the healthcare sector shares 48.7%, about 6 point increase from 42.5% in 2015 and a 10-point high of 37.5%, in 2017.

According to the National Household Survey (2015) of TIB, a large proportion of households (63.3%) receive healthcare services from private institutions alongside public ones. But its 2021 report reveals that, due to Covid-19, the number of healthcare service recipients increased to 92.9 per cent of 90.6 per cent of patients received healthcare from public healthcare facilities across the country.

According to the Health Bulletin 2015 of the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS), a substantial number of Bangladeshi physicians (60.3%) is associated with private healthcare activities. Over the four decades, the number of registered private healthcare service-providing institutions has had an astounding growth – from a mere 33 in 1982 it increased to 15,728 with 91,5537 seats, according to the Health Bulletin 2019, (15,698 in 2017.)11

However, allegations of various irregularities and corruption are being published in various mass media reports as well as research findings against the private institutions, which include, inter alia, higher treatment cost, wrong diagnosis of diseases, commission-based services, running of healthcare services without registration, and overall deficiency in the expected service quality, etc. There is a dearth of comprehensive investigative research on the governance of this sector although various research and discussions questioned the quality of private healthcare.11

Healthcare receivers informed that in some cases they did not get full-time support of the doctors according to their needs, especially at night in a time of medical emergency. No doctors were found during post-operative complexities or follow-ups at Upazila or district levels, as the specialist doctors come for consultation from outside of the locality for one or two days.

TIB’s findings and apparent facts reveal that in the healthcare sector, a commission-based marketing system has been developed over the decades. The collusion among public and private doctors, health assistants, family planning workers, village doctors, medicine sellers (pharmacy owners) of drug houses, midwives, receptionists of private healthcare institutions, rickshaw pullers and professional brokers has gripped the sector. There are allegations that sometimes the care receivers in the private facilities are forced to buy additional medicines, and the remaining ones are sold outside later.

An amount of 25% to 50% given to the persons who are involved in the commission chain. Even commission is given for sending cases for the C-section, and the amount ranges from TK. 500 to TK. 5,000. It is alleged that sometimes service recipients are harassed by professional brokers, as they divert the patients to another institution either by giving wrong information or by force. Such incidents happen mostly to illiterate or unaware people who come from rural areas.11

According to the survey, 86.1% of the surveyed households received health services, among whom 56.6% received health services from the government, 63.3% from private, 0.1% from institutions outside the country and 0.9% from NGOs.

Irregularities and corruption: Among the households that received health services from government institutions, 37.5% became victims of different kinds of irregularities and corruption. Among the service recipient households, 16.7% had to pay a bribe or extra money, 13.8% faced irregularities with regard to medicine, 6.2% were advised to go to private clinics or diagnostic centres, 4.8% was reported the unavailability of doctors/medical assistants when required, and 1.2% reported the presence of representatives of pharmaceutical companies while receiving services from the physician. The households that had to pay bribes TK 196 on average.10

Institutional Irregularities and Corruption: maximum number of households (32.2%) received healthcare from Upazila Health Complex. However, the rate of corruption was highest in District Sadar/General Hospital (52.4%). The rate of bribery or illegal payments was highest in medical colleges (12%). According to the survey data, the average bribe or illegal amount per household paid was comparatively highest in District Sadar/General Hospital (BTD 704 per household) and the lowest at Community Clinic (average BDT 17 per household). On the whole, those who received healthcare services from the sub-district level facilities paid BDT 680 on average. The amount of bribes or of irregular money is BDT 743 per household in rural areas and 637 per household in urban areas.

It can be observed that in receiving various types of health care from government institutions, service-receiving households are subject to corruption and giving bribes or illegal payments. In this case, the rate of victims of household of corruption is the highest (66.4%). Apart from this, 56.5 per cent in trolley/wheelchair use, 55.1 per cent in sewing/bandage/dressing services and 42.8 per cent in corona vaccination registration reports TIB.

The highest amount of bribe is also paid at Medical College Hospitals (TK 283 on average), while the lowest is at Community Clinics (TK. 31 on average).10 Service-wise corruption and irregularities: Among the households which had to pay for service, the highest number (53.7%) had to pay for use of trolleys and wheelchairs, followed by bandage and dressing services (26%), operation services (16.5%), maternity services (14.9%), purchase of tickets (11.9%), diagnostic tests (10.8%), and availing general/ cabin and paying beds (7.4%).10

“The highest amount the households had to pay (TK. 1,168 on average) was for operation services, closely followed by TK. 1,145 on average paid for maternity services. The survey finding reveals that on average, an out-patient spent Tk. 90.1, while for the inpatient the average amount spent was Tk. 2477.5.

The cost of treatment for out-patients varies between Tk. 132.7 and Tk. 17.0 depending on the type of facility. In the case of inpatients, this amount ranges between 1,836 Taka and 3,117.94 Taka. The average amount spent by an out-patient in a district hospital was almost six times more than the amount spent by an out-patient at a UHFWC (Tk. 132.7 vs. Tk. 17.0). Similarly, the average amount spent by an inpatient visiting a district hospital (Tk. 3117.9) was almost twice the amount spent by an in-patient at the UHC (Tk. 1,856.9).2

Corruption in the form of bribery limits both the indoor and outdoor services in city hospitals. The TIB report estimates that payments of around Tk. 4 million in bribes are made annually in order to get beds for patients in DMCH alone. The report also identifies a group of third-class staff who control important sections of DMCH, and who ensure that no help is received, even in emergencies, without payment. The situation is similar in other tertiary, district and then a level hospitals, in which timely doctor’s visits, buying tickets required for service, obtaining beds and access to essential medical equipment are all purchased through an organised group.2

65 per cent of patients were prescribed an inappropriate (or potentially inappropriate) drug or an inappropriate dosage, frequency and duration. The study says, patients are given an initial prescription and advised to buy the full dosage in a private pharmacy, implying that the practice is done for the personal benefit of doctors. As an incentive for prescribing medicines of selected pharmaceutical companies, physicians get a wide range of rewards including monthly payments, air tickets, payments of mobile phone bills, etc.; such practices are illegal according to the law.12

Other evidence has emerged of corruption in drugs and equipment in public hospitals. A recent report by Transparency International Bangladesh shows that in Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH), the country’s largest hospital, 65 per cent of indoor patients and 68 per cent of outdoor patients receive some free medicine.

That fourth class and other lower-ranking government employees sell costly medicines and other equipment is evidential. The TIB report on DMCH states that: There is a designated form to give free medicine to the patients. Only those patients are eligible to get free medicine whom doctors give prescription on this form. The fourth-class dishonest employees involved with medicine smuggling manage to steal these forms. Then they write down the names of the medicine on them, copy the signature of a doctor, draw medicine from the store and sell them in outside pharmacies.2

The evidence from the present study shows that getting admission in a public health facility is a lengthy and costly procedure, frequently involving unofficial payments.

10 per cent of the patients needed a recommendation from influential persons (bureaucrats, political leaders, MPs, etc.). The study also found that:

- People from poorer households have at least the same risk of making unofficial payments as those from richer households.

- Since the poor are less likely to have friends or connections at the hospital and they are even less likely to obtain recommendations from influential people (bureaucrats, politicians), they are likely required more frequently to make unofficial payments.

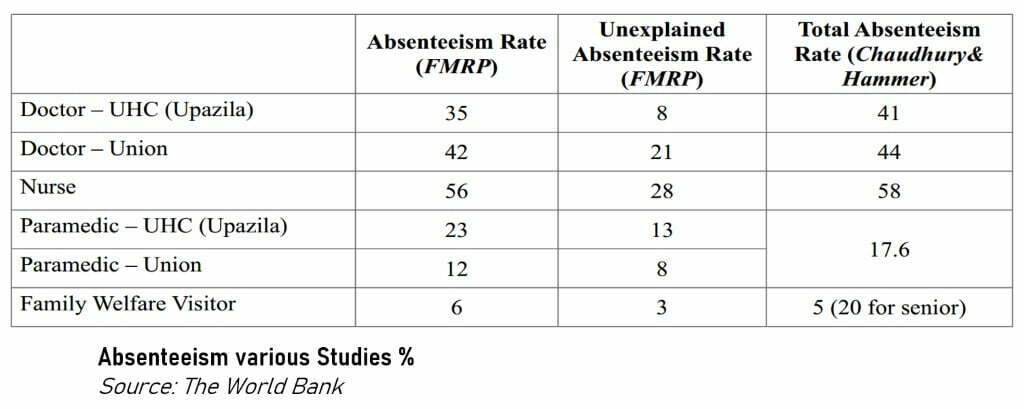

Regarding staff absenteeism, there are two problems to confront. The most important problem is that many posts at the public hospitals do not get filled in at all, that is, these posts are lying vacant. The other important problem is that even when positions are filled up, the doctor may not be there to attend to the patients i.e. the doctor is ‘absent’ from duty. These absent personnel receive their salaries (and other allowances) but are not regular in attendance. If doctors and other service providers are not on the job, the expenditures embodied on them also do not reach the (intended) beneficiaries.

“Absentee rates at over 40%, are particularly high for doctors. When separated into the levels of the facility, the absentee rate for doctors at the larger clinics is 40% but at the smaller sub-centres with a single doctor, the rate is 74%. Absent personnel, on the other hand, still receive their salaries. Why is staffing rural clinics so difficult?

One hypothesis is that most medical practitioners in developing countries generally and in Bangladesh specifically, are urban born and bred, highly educated relative to the population at large, and have skills that are both highly marketable and lucrative. If married with a family, they are likely to want the same for their children. Altogether, not the kind of person one would expect to want to live in rural areas.13

Healthcare service providers at a glance

Bangladesh government has sanctioned 27,002 positions for physicians of which 25,594 are currently filled up, which means a total vacancy of 44.2%. In total 13,483 nurses are currently working in public health facilities, while the total number of positions sanctioned are 17,183. The Distribution of vacant positions of different levels of nurses shows that around 96 per cent of positions of senior nurse are vacant. During 2018-2019 under the 37th and 39th BCS respectively, totalling 4,905 posts. Two hundred ninety posts for dental surgeons were created during 2018-2019 under the 39th BCS (Health bulletin 2019).

A total of 26,635 sanctioned posts remained vacant of 1,05,254 which constituted 25.31% of the total sanctioned posts. Vacancy rate was 5.21% for doctors and 57.20% for non-doctors.

The scope of medical education has been extending beyond public medical institutions since the beginning of the 1990s. A sum of 70 private medical colleges can educate 6,231 physicians. 26 private dental colleges have the capacity to educate 1,405 dentists. A sum of 530 nurses, 140 midwives and 1,855 medical assistants can be graduated from private institutions.

The number of hospitals under DGHS is 739 contributing healthcare facilities across the courtly. There are 5,231 registered private clinics, 9529 diagnostic centres, 54,660 hospital beds under DGHS, number of private hospitals are 91,537. There are currently 36 government and 70 private medical colleges, and 2,258 gov facilities under DGHS. 15 government and 45 private nursing institutions offering BSc. A total of 12,082 seats for MBBS, 4,068 in government and 6,231 in private medical colleges and 1783 for foreigners available.

There are 105,254 personnel working currently working under DGHS, 27,002 doctors including sanctioned posts, 101,538 registered physicians which are 1,487 people for per registered physician, for per 10,000 people are only 6.73 registered physicians while for per 10,000 people, there are 1.55 doctors working under DGHS. For per 10,000 people there only 3.30 public hospital beds, the private rate is higher, 5.53 for per 10,000 people with a total of 91,537 beds.

However, statistics on the number of physicians actually graduated from private institutions are not available.1 The patients are regularly being deprived of health facilities due to a number of irregularities and corrupt practices. Limited resources, shortage of necessary equipment and medicines and an abnormally disproportionate ratio of doctors and nurses against patients- all these are realities in the context of medical services in Bangladesh.14

The highest vacancy in medical staffs is observed in Barisal (64.9%), followed by Khulna (58.2%), Rajshahi (55.3%), Sylhet (54.7%), Chittagong (50.7%) and Dhaka (25.4%). There are currently 20 public medical colleges in Bangladesh of which 17 have the capacity to produce 2,509 physicians and the rest can produce 210 dentists. A total of 1,250 places for nursing education are available in public institutions. Furthermore, places for educating 650 medical assistants are available in public institutions. From the public medical colleges, 10,990 physicians have been graduated between 2004 and 2009 of which 49.2 per cent is female.1

Bangladesh Health Watch Report 2013 found that “Bangladesh has only 7.7 doctors/nurses/dentists per 10,000 population compared to 12.5 for Pakistan,14.6 for India, 21.9 for Sri Lanka, and WHO estimate of 23 per 10,000 required to fulfil MDG targets. The current nurse-doctor ratio of 0.4 (i.e. 2.5 times more doctors than nurses) is far short of the international standard of around three nurses per doctor. There is also a gross imbalance in the doctor-technologist ratio as well, the ideal being five technologists for one doctor. According to the WHO estimate, Bangladesh has a staggering shortage of 60,000+ doctors, 2, 80,000 nurses and 4, 83,000 technologists!”15

Punishment for medical negligence in Bangladesh

There is a financial burden, there is corruption but there are not adequate laws for the victims. Patients, especially poor ones, are in between rock and hard place. It is a regular hostage situation for the patients. There is no explicit provision in Bangladesh in favour of patients in chase victimised by professional negligence by medical professionals.

In most countries, medical negligence is generally viewed as an actionable civil wrong, the remedy for which is commonly monetary compensation. In common law jurisprudence, it comes within the purview of the law of torts.

Some countries deal with the matter generally under the law of torts, such as Malaysia; while some countries provide for separate legislation with a specific judicial forum to redress such wrongs e.g. in India medical negligence cases are adjudicated under the Consumer Protection Act. Medical negligence or malpractice, however, may sometimes give rise to criminal offence as well. Such offences are generally dealt with by the penal laws of the country.16

Medical Negligence is an issue of serious human rights concern that directly affects the right to life and right to health care. The overwhelming number of incidents of medical negligence in Bangladesh mostly goes without any legal action, leading to a frustrating situation where public trust is completely lost on the medical service providers.

Although the legal remedies available under the existing laws are limited or difficult to access, such efforts give a clear idea about the shortcoming of the existing law and the underlying difficulties in the judicial system. The Constitution of Bangladesh recognizes the right to health care and guarantees the right to life. Bangladesh is also a party to a number of international instruments, under which the Government has an obligation to protect and promote the right to health.17

“Frequent malpractice in private and public hospitals causes raise concerns as thousands of injuries and deaths occur every year. In addition to inadequate medicine, and healthy ambience common people still fail to get proper treatment even at the cost of everything. People have faced inappropriate treatment, misbehaviour and inhuman conduct by health professionals as if they are superior beings and those who go to them inferior enough to be abused by them.

People every day have to endure maltreatment and sometimes die because of medical treatment or health providers’ negligence in the country. Existing law is not well-defined to address the remedy against medical malpractice properly. Due to the absence of effective application of laws medical professionals are taking full advantage of their professional indemnity.14

In Bangladesh, patients belong to the most neglected sector of consumers. Patients’ rights have never been thought of or taken into account seriously. The role of healthcare professionals is seen as a money-making industry and patients are seen or treated as consumers of health services. The notion of the health care industry or health-providing mechanism has emerged due to “physicians as entrepreneurs or as workers in an entrepreneurial enterprise were enmeshed in the mutual competition”.17

“Medical negligence can be defined as the treatment by a medical professional that does not meet the medically accepted standard of care. In other words, Medical negligence is professional negligence by an act or omission by a health care provider in which care provided deviates from accepted standards of practice in the medical community and causes injury or death to the patient, with most cases involving medical error. It is a breach of duty by a doctor to perform his or her job as required by their duty”.17

Negligence is the breach of a legal duty of care. A breach of this duty gives the patient a right to initiate action against negligence. All medical professionals, doctors, nurses, and other healthcare providers are responsible for the health and safety of their patients and are expected to provide high-level quality care. Unfortunately, medical professionals and health care providers can fail in this responsibility to their patients by not giving them proper care and attention, acting maliciously, or by providing substandard care, thus causing far-reaching complications like personal injuries, and even death.18

Inadequate skill, care, or speed can be the causes of medical negligence claims. Any person, including doctors, nurses, or specialists, who assume any part of the responsibility for a patient’s medical care can be held liable for medical negligence. Those professionals who provide psychological care are also responsible for the wellbeing of patients and could be charged with malpractice.13

Based on the report published by ASK it is certain that there are at least 504 medical negligence-related deaths or loss of organs by patients from 1995 to 2008 in Bangladesh. ASK says, “This figure, obviously could be much higher if all the incidents had been counted, and if unreported incidents had also been taken into account.18

Misdiagnosis, delayed diagnosis, surgical errors, unnecessary surgery, error in anaesthesia, negligent anaesthesia preparation, failure to monitor anaesthetic performance, wrong surgery, medical negligence and C-section, mistreatment of a difficult birth, the complication with induced labour and negligent long term treatment fall on the criteria of medical malpractice or negligence.

Many incidences go unreported because “ the overwhelming number of the patients are poor people who are considered to be the victims of medical negligence think that they are predestined for this sort of professional maltreatment by the medical professionals. They hardly seek for the redress and even if the redress is sought for by the victims, the result is predictably negative any sought redress for the professional malpractice trigger negative consequences to the victims making the situation even worse.

According to the Bangladesh chapter of human rights watch Ain O Shalish Kendra (ASK), “Depending on the nature and culpability of the alleged act, medical negligence and fraudulent or ill practices involving medical profession or service can also come within the purview of the general penal law. The Penal Code of 1860 is the main penal law of Bangladesh that generally deals with different types of criminal offences.

Ascertaining the damage caused to the patient or victim is very important in litigations involving medical negligence. The damage must be actual and not too remote. The damage can be measured in terms of-

- additional financial expenses for treatment of the complication resulting as a consequence of negligence,

- loss due to absence from work,

- decreased life expectancy,

- loss of organ or limb,

- death of the patient who could be a wage earner for the family,

- loss of consortium etc.

The criminal complaints are being filed against doctors alleging the commission of offences punishable under Section 304A-

(Whoever causes the death of any person by doing any rash or negligent act not amounting to culpable homicide shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to 106 [five] years, or with fine, or with both.) or Sections 336 (Whoever does any act so rashly or negligently as to endanger human life or the personal safety of others, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to three months, or with fine which may extend to two hundred and fifty Taka, or with both.)

or 338 (Whoever causes grievous hurt to any person by doing any act so rashly or negligently as to endanger human life or the personal safety of others, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to two years, or with fine which may extend to 120[five thousand takas], or with both.) of the Penal Code, 1860 alleging rashness or negligence on the part of the doctors resulting in loss of life or injury of varying degrees to the patient.16

When any medical practitioner or dentist is found guilty of misconduct in respect of his profession, the Council may refuse to permit the registration of that person (Sec of 28i).17

Medical service providers can be prosecuted under sections 45 and 52 of the Consumer Rights Protection Act, 2009 if there is negligence or intentional act or omission leading to endangering the life and security of the patients. According to section 53, medical professionals may also be held liable if their negligence caused damage to money, health or life of service receivers. The Act provides that whoever does any act which can endanger the life or security of the consumer will be punished for imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years or with a fine not exceeding 200,000 Taka or with both.17

Conclusion

Even though there are no special and explicit laws mentioning and protecting patients’ rights in Bangladesh, the above-mentioned provisions can be a little solace to patients. From the above-mentioned incidences of medical care inaccessibility, negligence, and inability to be treated illness it has now been clear as to why financial capabilities matter when it comes to trying to live a little more time to survive with healthy physic. The current health policy in Bangladesh leaves no scope for patients, for the poor section of the population so to speak, not to be worried about health, health care and survival.

This piece does not contain a recommendation to the authorities of the Public and private health providers. It is rather to make people aware of how generally financially underprivileged people are being trapped under the healthcare facilities that are hardly meant for them. Because of the constantly rising healthcare costs, people from the lower-income group find it inaccessible or incapable of bearing.

Therefore, morbidity for Bangladeshis is an omnipresent concern. Moreover, constantly poor people’s right to health and life has been ignored by authoritative medical professionals for a long time. One’s inability to get healthcare does not mean someone is not entitled to the right to life.

The concurrent selective state of the healthcare system in Bangladesh yet again proves that only the privileged and capable people are the only being superior to survive. It is very self-evidential that the writer of the article himself is unsure of his future physical well-being and feasible survival privilege if any ailment takes him.

You may also like to read: Rohingya crisis in Bangladesh and its global political victim

Works Cited:

- Bangladesh Health Watch Report 2011. Watch, Bangladesh Health ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

- Access to Public Health Facilities in Bangladesh: A Study on Facility Utilisation and Burden of Treatment. MANNAN, M. A. s.l. : Bangladesh Development Studies, 2013, Vol. Vol. XXXVI. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

- Health for All in Gujarat: Is It Achievable? MAHADEVAN, DARSHINI. ↩

- The organization, World Health. The Right to Health. Geneva, Switzerland: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and WHO. ↩

- Cost of illness for outpatients attending public and private hospitals in Bangladesh. Md Sadik Pavel, Sayan Chakrabarty and Jeff Gow. 2016. ↩ ↩ ↩

- Healthcare use and expenditure for diabetes in Bangladesh. Sheikh Mohammed Shariful Islam, Andreas Lechner, Uta Ferrari, Michael Laxy, Jochen Seissler, Jonathan Brown, Louis W Niessen, Rolf Holle. ↩

- Who pays for healthcare in Bangladesh? Analysis of progressivity in health systems financing. Chi, Azaher Ali Molla and Chunhuei. ↩ ↩

- Paying Out of Pocket for Healthcare in Bangladesh – A Burden on Poor? Nazmul M HUQ, Abul Quasem AL-AMIN, Sushil Ranjan HOWLADER, and Mohammad Alamgir KABIR. ↩

- Deepening Health Insecurity in India: Evidence from National Sample Surveys since the 1980s. SAKTHIVEL SELVARAJ, Anup Karan. 2009. ↩

- Corruption in Service Sectors: National Household Survey 2015. Bangladesh, Transparency International. s.l. : Transparency International Bangladesh. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

- Private Healthcare: Governance Challenges and Way Out. Julkarnayeen, Taslima Akter and Muhammad. s.l. : Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB), 2017. ↩ ↩ ↩

- Jonathan Rose, Tracey M. Lane and Tashmina Rahman. BANGLADESH: GOVERNANCE IN SECTORS, Bangladesh Governance in the Health Sector: A Systematic Literature Review. 2017. ↩

- Ghost Doctors: Absenteeism in Bangladeshi Health Facilities. Hammer, Nazmul Chaudhury and Jeffrey S. 2003. ↩ ↩

- Negligence in Government Hospitals of Bangladesh: A Dangerous Trend. Farid, Md. Rabiul Islam and Shekh. s.l. : Institute of Social Welfare and Research (ISWR), 2015. ↩ ↩

- Bangladesh Health Watch Report 2013 ↩

- Medical Negligence and Fraudulent Practice in Private Clinics: Legal Status and Bangladesh Perspective. (ASK), Ain o Salish Kendra. 2013. ↩ ↩

- Medical Negligence Laws and Patient Safety in Bangladesh: An analysis. Sheikh Mohammad Towhidul Karim, Mohammad Ridwan Goni and Mohammad Hasan Murad. Journal of Alternative Perspectives in the Social Sciences, Vols. Volume 5 No 2, 424-442. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

- Medical Negligence: A Review of the Existing Legal System in Bangladesh. Reza, Kazi Latifur. 2016, Vols. Volume 21, Issue 10. ↩ ↩