Parasite (2019), a South Korean cinematic triumph by Bong Joon-ho, quickly became a cultural phenomenon, captivating audiences around the world with its sharp, biting social commentary and intricate storytelling.

In an era where the entertainment industry is frequently characterized by formulaic storytelling, Parasite emerges as a breathtaking anomaly—blending dark humor with profound social critique, this film explores themes of class inequality, deception, and survival.

Parasite made history when it won the Academy Award for Best Picture at the 92nd Academy Awards, becoming the first non-English language film to win this prestigious honor.

Alongside this monumental achievement, it also earned Oscars for Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best International Feature Film. Such accolades cemented Parasite as a defining masterpiece of contemporary cinema, both in South Korea and internationally.

Fundamentally, Parasite tells the story of two families, the struggling Kims and the wealthy Parks, whose lives become intertwined in a series of deceptive schemes that culminate in unexpected and shocking twists.

Bong’s direction, coupled with the exceptional performances of the cast, ensures that the audience is not only engaged by the plot but also moved by the larger message of socio-economic disparity. The film’s cinematography, particularly its use of space and the iconic staircases, visualizes the oppressive class distinctions that run throughout the narrative.

This review will delve into the film’s multifaceted layers: from its compelling plot and standout performances to its masterful cinematography and poignant themes.

By exploring these key elements, we will uncover why Parasite continues to resonate with audiences and critics alike, earning its rightful place among the best Korean movies and Oscar-winning films. Parasite is one of the 101 best must-watch films on my list.

Plot

Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2019) is a masterful blend of black comedy, thriller, and social commentary, encapsulating the stark divide between the rich and the poor through an intricately woven narrative.

Parasite tells the story of the Kim family, a working-class household struggling to make ends meet in Seoul. Living in a cramped semi-basement apartment, the Kims—father Ki-taek, mother Chung-sook, son Ki-woo, and daughter Ki-jung—rely on temporary gigs like folding pizza boxes to survive.

However, when an opportunity arises for Ki-woo to infiltrate the wealthy Park household under false pretences, it sets off a chain reaction that entangles both families in unexpected ways.

Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2019) is not just a film; it is a meticulously crafted cinematic experience that intertwines black comedy, social critique, and thriller elements into a seamless narrative.

Through his signature storytelling style—marked by sudden tonal shifts, precise visual metaphors, and a deeply humanistic yet critical perspective—Bong constructs a harrowing commentary on class struggle, economic disparity, and social mobility.

1. The Infiltration of the Kim Family

The film opens in a dimly lit, cluttered semi-basement apartment, where the Kim family—father Ki-taek (played by Song Kang-ho), mother Chung-sook (played by Jang Hye-jin), son Ki-woo (played by Choi Woo-shik), and daughter Ki-jung (played by Park So-dam)—struggles to make ends meet. Their survival is sustained by folding pizza boxes and scavenging for free Wi-Fi, a strikingly realistic depiction of South Korea’s economically marginalized underclass.

A turning point arrives when Ki-woo’s friend, Min-hyuk, offers him a lucrative opportunity: to tutor Da-hye, the teenage daughter of the wealthy Park family.

However, there is a catch—he must forge a college diploma to secure the position. His sister Ki-jung, an exceptionally talented artist, fabricates a certificate, and Ki-woo assumes the name “Kevin,” successfully deceiving the naive but well-meaning Park mother, Yeon-gyo (played Cho Yeo-jeong).

Recognizing an opportunity, the Kims devise a cunning scheme to integrate themselves into the Parks’ household. Ki-woo, under the guise of concern, recommends an “art therapist” for the Parks’ hyperactive young son, Da-song (Jung Hyeon-jun).

This therapist is none other than his sister, Ki-jung, who assumes the identity of “Jessica.” Her psychological manipulation convinces Mrs. Park that Da-song requires her services.

Step by step, the Kims family eliminate existing household staff to secure employment for themselves. The chauffeur, Yoon, is dismissed after Ki-jung strategically plants a pair of underwear in his car, creating the illusion of inappropriate behavior. Ki-taek, the patriarch, is then hired as the replacement driver. Finally, they orchestrate the firing of the longtime housekeeper, Moon-gwang (played Lee Jung-eun), by exploiting her severe peach allergy—leading Mrs. Park to believe she has tuberculosis. Chung-sook, the Kim matriarch, is then introduced as the “perfect” housekeeper.

At this stage, Bong Joon-ho’s storytelling is at its most satirical—highlighting how meritocracy is a myth when personal connections and deception dictate one’s upward mobility.

The Kims, though resourceful and skilled, can only access better opportunities through deception, reflecting the harsh economic reality faced by South Korea’s lower class.

2. The Parasitic Coexistence

With all four of the Kims now employed by the Parks, they revel in their newfound luxury. When the Park family leaves for a camping trip, the Kims indulge in an extravagant night, drinking expensive whiskey and lounging in the lavish home.

However, their temporary euphoria is shattered when the doorbell rings.

It is Moon-gwang, the former housekeeper. Claiming to have left something behind, she pleads to be let in. What follows is one of Parasite’s most stunning narrative twists: Moon-gwang reveals a hidden underground bunker where her husband, Geun-sae (played Park Myung-hoon), has been secretly living for years to escape debt collectors.

This revelation disrupts the delicate balance of power within the household.

When Moon-gwang discovers the true identities of the Kims, she turns the tables by recording a video as blackmail. A violent scuffle ensues, and the Kims manage to subdue the couple, locking them in the basement.

Here, Bong Joon-ho escalates the class conflict from subtle satire to direct confrontation.

The film no longer depicts a parasitic relationship between the poor and the rich but an internal struggle among the lower class—highlighting how systemic oppression forces the impoverished to fight among themselves rather than unite against the elite.

3. The Rainstorm

Just as the Kims believe they have regained control; the Parks call to inform them of their unexpected return.

In a frantic sequence, the Kims scramble to clean the house and hide under the living room furniture as the Parks settle in. During this moment, Ki-taek overhears Mr. Park (played by Lee Sun-kyun) commenting on his “smell”—a distinct odor associated with the lower class.

After the Parks fall asleep, the Kims barely escape and return home, only to find their semi-basement apartment flooded due to a heavy rainstorm.

This sequence is one of the film’s most visually arresting moments, as Bong contrasts the two families’ drastically different experiences with the rain: for the Parks, it is an inconvenience that cancels their camping trip; for the Kims, it is a disaster that renders them homeless.

The next day, the Parks throw an impromptu garden party for Da-song’s birthday.

Ki-woo, believing he can solve the situation, sneaks into the bunker with a scholar’s rock—a symbol of wealth given to him earlier in the film. His intention is to silence Geun-sae, but instead, he is brutally attacked.

Geun-sae then emerges from the basement, deranged and vengeful.

In a shocking turn of events, he stabs Ki-jung in the chest, causing chaos at the party. As Da-song suffers a seizure from the shock, Mr. Park demands Ki-taek to hand him the car keys. At that moment, Ki-taek—having endured repeated humiliation—snaps and fatally stabs Mr. Park before fleeing the scene.

4. The Illusion of Hope

Weeks later, Ki-woo awakens from a coma to learn that Ki-jung has died, his father is missing, and his mother is on probation. He soon discovers that Ki-taek has taken refuge in the basement bunker, sending messages through Morse code via a flickering light.

In a heart-wrenching final sequence, Ki-woo imagines a future where he earns enough money to buy the Park’s former house and free his father.

However, Bong Joon-ho delivers a cruel twist: the fantasy dissolves, and Ki-woo is still in the same semi-basement. His dream of upward mobility is just that—a dream.

This ending solidifies Parasite’s central thesis: the social hierarchy is nearly impossible to escape. The film masterfully exposes the illusion of class mobility, illustrating how economic disparity traps individuals in an endless cycle of struggle.

Themes & Social Commentary in Parasite

Class Struggle & Wealth Inequality

The Kims live in a semi-basement (banjiha), a common low-income housing situation in South Korea, exposing them to unsanitary conditions and frequent flooding. Their existence is juxtaposed against the Parks’ luxurious modernist home, a stark symbol of privilege.

The visual metaphor of verticality—where the rich reside at the top and the poor are literally below—reinforces this disparity.

The Kims represent the modern underclass, struggling to find stable employment in a society where financial mobility seems nearly impossible. Their luck takes a turn when Ki-woo’s friend recommends him for a lucrative tutoring position for Da-hye, the teenage daughter of the affluent Park family.

To secure the job, Ki-woo forges a university degree with the help of his sister, adopting the persona of “Kevin” to impress the naive Mrs. Park. His newfound access to the Parks’ extravagant mansion becomes the family’s golden ticket.

With meticulous planning and a dash of theatrical performance, Ki-woo engineers a way to bring in his sister, Ki-jung, as an ‘art therapist’ for the Parks’ young son, Da-song.

The Parks, oblivious to the ruse, remain blissfully unaware that their entire domestic staff is now composed of a single, well-coordinated family masquerading as unrelated professionals.

Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite is an unflinching critique of economic disparity, portraying the stark contrast between the affluent Park family and the struggling Kim family.

The film also critiques the exploitation inherent in capitalism. While the Kims are depicted as parasitic intruders in the Park household, the Parks, in turn, parasitize the labor of the underprivileged.

Bong himself has stated, “If you look at it the other way, you can say that the rich family are also parasites in terms of labor. They can’t even wash dishes or drive themselves”.

Social Mobility & Deception

The Kims’ ascent into the Park household is built on deception, illustrating the lengths to which the working class must go to achieve upward mobility.

Ki-woo’s adoption of the fake identity “Kevin” with a forged Yonsei University diploma encapsulates the impossibility of climbing the social ladder through conventional means. The Parks, oblivious to the realities of lower-class struggles, view their employees as mere service providers, their concerns secondary to the family’s comfort.

A pivotal moment is when Mr. Park, upon detecting an unpleasant smell from Ki-taek, remarks that it is “the smell of people who ride the subway”.

This comment, casual yet devastating, highlights the insurmountable divide between the classes. Despite their careful maneuvering, the Kims are ultimately dispensable to the Parks, reinforcing the theme that the elite’s kindness is conditional and transactional.

Symbolism & Hidden Meanings

Bong Joon-ho masterfully infuses Parasite with rich symbolism.

The Scholar’s Rock, given to the Kim family as a token of promised wealth, is ironically what ultimately injures Ki-woo, underscoring the futility of chasing the illusion of prosperity, according to Britannica.

The basement bunker, an unseen yet integral part of the Park home, serves as a metaphor for the hidden underclass that exists beneath society’s surface.

Staircases play a crucial role in delineating social hierarchy. The Kims ascend physically into the Park home and descend back into the flooded ruins of their own reality. This use of spatial metaphor reinforces the impossibility of true mobility in an unjust system.

Genre-Bending & Satire

Parasite defies genre conventions, seamlessly blending elements of comedy, thriller, and tragedy.

The film’s first half has a lighthearted, almost heist-like energy as the Kims infiltrate the Park home.

However, the tone shifts dramatically after the revelation of Moon-gwang’s hidden husband. The final act descends into chaos, culminating in an eruption of violence that underscores the futility of class rebellion.

Bong’s signature satirical approach is evident in the way the Parks’ ignorance and the Kims’ desperation intertwine. He draws from real-world frustrations in South Korea, where economic instability has led to widespread disillusionment, encapsulated in the term “Hell Joseon”.

Parasite is more than a critique of wealth inequality—it is a mirror reflecting society’s deepest flaws. The film’s themes of class struggle, social mobility, and systemic oppression resonate globally, making its acclaim well-earned.

Bong Joon-ho’s masterful storytelling ensures that Parasite remains one of the most compelling social commentaries in modern cinema.

Cinematography & Direction

Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2019) is a cinematic tour de force, blending sharp social commentary with precise visual storytelling. Through meticulous cinematography, set design, and directional choices, Bong crafts a film that is as visually engaging as it is thematically profound.

Bong Joon-ho’s Storytelling Style

Bong Joon-ho’s storytelling in Parasite is laden with irony, dark humor, and moments of razor-sharp tension. The film’s genre-bending structure allows it to shift seamlessly from comedy to thriller, keeping audiences engaged while delivering a biting critique of wealth disparity.

The Kims’ con artistry is at once amusing and anxiety-inducing, reflecting the desperation of the working class in their pursuit of economic stability.

As the Kims bask in the luxuries of their new life, a sudden revelation threatens to unravel their carefully constructed scheme.

Bong expertly introduces twists that deepen the social commentary without resorting to heavy-handed exposition. The film examines themes of privilege, dependency, and the precarious nature of economic survival, making Parasite much more than a simple heist story—it’s a mirror to class divisions that resonate globally.

7 Lessons From Parasite

1. Class Divide is Spatial, Not Just Economic

Bong Joon-ho masterfully crafts a physical metaphor for class disparity.

The semi-basement where the Kim family resides represents the liminal space between the surface world of the affluent and the underground destitution epitomized by the hidden bunker beneath the Park household. The literal descent of characters—be it Ki-woo’s journey to the bunker or Mr. Kim’s retreat into darkness—symbolizes a societal trap where those at the bottom can never truly ascend.

The torrential flood, which devastates the lower-class neighborhoods but barely affects the Parks, highlights the indifference of privilege (“Even after the rain, the sky was so blue and pretty” – Mrs. Park, oblivious to the Kims’ suffering).

2. The Illusion of Social Mobility

One of the film’s most tragic realizations is that social mobility is often an illusion.

Ki-woo dreams of buying the Park residence to liberate his father, but the final scene reveals that this is merely a fantasy. The stark cut back to the flooded basement underscores the harsh reality that hard work and intelligence are insufficient in breaking systemic barriers.

As Choi Woo-shik, who plays Ki-woo, remarked, “It would take him 564 years to buy that house.”

3. Wealth Breeds Dependence

While the title Parasite initially appears to describe the Kim family’s infiltration into the Park household, Bong Joon-ho subverts this expectation. The wealthy Parks are equally dependent on their servants—they lack the basic skills to maintain their own home or even cook (“What do we do about dinner?” asks Mrs. Park when her housekeeper is fired).

This co-dependent relationship challenges traditional narratives that frame the poor as leeches upon the rich. In reality, the elite’s comfort is built upon the labor of the working class.

4. Prejudice and Privilege

Mr. Park’s disdain for Mr. Kim’s ‘smell’ is not just about personal hygiene—it is a symbol of class distinction.

“That smell crosses the line,” he remarks, reinforcing how the upper class perceives poverty not just as a condition but as something inherently repellent.

The Parks are polite, yet their quiet disgust underscores the insidious nature of class-based discrimination: it is not just overt oppression but the microaggressions and unspoken judgments that maintain division.

5. Desperation Breeds Conflict

Rather than uniting against their oppressors, the struggling classes in Parasite turn on each other.

The Kims’ conflict with the former housekeeper, Moon-gwang, and her husband, Geun-sae, descends into a brutal struggle for survival. In a society where resources are scarce, solidarity is often overshadowed by self-preservation. This aligns with Marxist critiques of capitalism, where lower classes are pitted against one another rather than challenging the system itself.

6. The Dream of Change

Bong Joon-ho describes the final shot of Ki-woo back in the basement as a ‘surefire kill’—a cinematic coup de grâce that eradicates any lingering hope of his success.

Unlike Hollywood narratives that offer redemption arcs, Parasite closes the door on such illusions. By mirroring the opening shot, Bong suggests a cyclical trap: the poor remain poor, and aspirations of social ascension are nothing but cruel fantasies.

7. Satire and Horror Are Two Sides of the Same Coin

Bong seamlessly blends dark humor with creeping dread, showing that satire and horror often stem from the same source: social dysfunction.

The absurdity of the Kims’ cons and the brutal violence of the climax serve the same purpose—to expose the precariousness of human existence under capitalism. Laughter and fear are not opposites in Parasite; they are intertwined responses to the absurd inequities of modern society.

In the words of Bong Joon-ho himself: “The most personal is the most creative.” Parasite is both deeply Korean and universally resonant, capturing the anxieties of a world where wealth divides and aspirations are often unfulfilled dreams. The film forces us to reflect: who, in this system, is truly the parasite?

Framing

Cinematographer Hong Kyung-pyo utilizes framing to reflect the hierarchical structures within Parasite. The contrast between the cramped semi-basement of the Kim family and the expansive, open-plan mansion of the Parks illustrates stark economic disparities. The staircases serve as a recurring motif, symbolizing social mobility—or the lack thereof.

For instance, in scenes where the Kim family hides under the Park family’s table, the camera’s low-angle shots emphasize their subservient position.

Conversely, when Mr. Park observes Mr. Kim’s “smell,” the camera subtly shifts perspectives, reinforcing the invisibility of the working class in the eyes of the elite.

Kim Family’s Semi-Basement: the Marginalized

The Kim family’s home is half-below ground, signifying their liminal existence—neither fully included in society nor entirely destitute. The low ceiling, cluttered space, and small window facing a back alley reinforce their struggle for survival.

Notably, the recurring scholar’s rock they receive is a visual irony—meant to symbolize fortune, yet ultimately becoming a weapon of destruction.

Park Family’s Mansion: Luxury and Isolation

Designed by a fictional architect within the film, the Park mansion epitomizes modernist wealth. The wide glass windows, minimalist interiors, and excessive space are visually appealing but also starkly impersonal. The house’s layout serves as a stage for power dynamics—with clear spatial separations between the Parks and their employees.

A crucial design choice is the hidden bunker, an architectural anomaly that embodies class suppression, serving as a dark counterpoint to the open, sunlit main floor.

Acting Performances in Parasite

Few films in cinematic history have captured the intricate dynamics of class struggle as profoundly as Parasite (2019).

Bong Joon-ho’s masterwork, lauded for its incisive social commentary, owes much of its emotional depth and narrative power to the performances of its stellar ensemble cast.

From Song Kang-ho’s subtle yet devastating portrayal of a disillusioned patriarch to the chillingly oblivious privilege embodied by Lee Sun-kyun and Cho Yeo-jeong, every performance in Parasite is a testament to the transformative power of acting.

Song Kang-ho as Ki-taek: The Everyman’s Tragedy

Song Kang-ho, a fixture in Bong Joon-ho’s filmography, delivers a tour de force as Ki-taek, the Kim family’s father. His ability to oscillate between comedy and pathos makes him one of the most formidable actors in Korean cinema.

Ki-taek begins as a man resigned to his socioeconomic fate, masking his despair with hopeful schemes. However, as the narrative unfolds, his quiet desperation simmers into a breaking point. The pivotal moment arrives when Mr. Park (Lee Sun-kyun) recoils at his odor, a symbolic line between the classes. Song’s barely perceptible flicker of pain in this moment conveys volumes about years of humiliation and struggle.

His final act—stabbing Mr. Park in a blind fit of rage—isn’t merely a loss of control but the culmination of years of suppressed anger and societal resentment.

As Bong Joon-ho describes, Parasite is a “stairway movie”, and Ki-taek’s downward spiral mirrors his literal descent into the hidden depths of the Park family’s bunker. Song Kang-ho’s performance ensures that we don’t just witness Ki-taek’s downfall—we feel it.

A Perfect Ensemble: The Power of Parasite’s Cast

Beyond individual performances, Parasite succeeds because of its ensemble synergy.

The actors play off one another with seamless chemistry, creating a world that feels lived-in rather than performed. This cohesion was recognized when Parasite won the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture—the first non-English-language film to do so.

Parasite is a cinematic achievement not just in storytelling but in acting. It is through the raw, layered, and deeply human performances of its cast that Bong Joon-ho’s vision of class conflict transcends cultural barriers.

Whether through Song Kang-ho’s tragic descent, Park So-dam’s cunning confidence, or Cho Yeo-jeong’s blissful detachment, Parasite resonates because its characters feel painfully real.

Awards & Box Office Performance of Parasite

Cinema has always been a reflection of society, but every once in a while, a film transcends the screen and becomes a cultural moment.

Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2019) did just that.

It was not merely a movie; it was a statement, a cinematic revolution that shattered barriers and set records that were once deemed unattainable. The film’s journey from the Palme d’Or at Cannes to making history at the Academy Awards, and its staggering box office performance, is a testament to its artistic and commercial brilliance.

A Groundbreaking Night at the Oscars

The 92nd Academy Awards were nothing short of historic. Parasite swept four major awards: Best Picture, Best Director (Bong Joon-ho), Best Original Screenplay, and Best International Feature Film.

This was an unprecedented feat—the first time a non-English language film took home the coveted Best Picture award. It was a moment that redefined global cinema, proving that storytelling transcends language.

Bong Joon-ho’s acceptance speech was equally memorable. He paid homage to his fellow nominees, particularly Martin Scorsese, whose influence shaped Bong’s filmmaking.

As the South Korean director held his golden statuette, the world watched as a new era of cinema unfolded, where geographical and linguistic boundaries could no longer confine artistic brilliance.

Before its Oscar triumph, Parasite had already made history at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival by winning the Palme d’Or, the festival’s highest honor.

The Palme d’Or is often seen as an indicator of cinematic excellence, but Parasite took it a step further by bridging the gap between critical recognition and commercial success, a balance that few films achieve.

Box Office Triumph

If awards signify artistic merit, box office earnings reflect public embrace, and Parasite excelled in both. With a worldwide gross of over $262 million against a modest $11.4 million budget, Parasite became one of the highest-grossing Korean films of all time.

The film’s financial success was not just limited to its home country; it resonated with international audiences, breaking records in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia.

In the U.S., Parasite earned an impressive $53.4 million, an extraordinary figure for a foreign-language film. It had one of the strongest per-theater averages, and after its Oscar victory, its box office revenue surged by over 230% in just one week.

This was a phenomenon previously seen with films like Slumdog Millionaire and The King’s Speech—except Parasite was entirely in Korean, proving that subtitles were no longer a barrier to success.

A Lasting Legacy

Parasite was more than just an Oscar-winning film; it was a movement. It shattered the preconceived notions of international cinema and set a new standard for what films can achieve on a global scale. As Bong Joon-ho famously stated, “Once you overcome the one-inch-tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films.” With Parasite, that barrier was not just overcome—it was obliterated.

The film’s impact is still being felt, from streaming platforms to academic discussions on class and capitalism. And in the end, isn’t that the true hallmark of a masterpiece? The ability to entertain, challenge, and inspire—all while rewriting history.

Related films

When discussing Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2019), it’s crucial to position it within the broader context of Korean cinema and its thematic parallels with other thought-provoking films.

A robust internal linking strategy enhances user engagement by offering readers a deeper dive into related works, guiding them through an interconnected cinematic journey.

Oldboy (2003): Directed by Park Chan-wook, this psychological thriller explores themes of revenge, identity, and the consequences of past actions. The film’s intricate storytelling and visceral intensity make it a must-watch for fans of Parasite.

Train to Busan (2016): A gripping zombie thriller by Yeon Sang-ho that subtly critiques social hierarchies and governmental failures, much like Parasite.

The film’s commentary on class divisions during a crisis draws compelling parallels with Bong Joon-ho’s work.

Parasite’s genius lies in its scathing critique of class struggle, a theme that has been explored in numerous films worldwide. By drawing connections to similar movies, we help audiences place Parasite in a global context of socio-political storytelling.

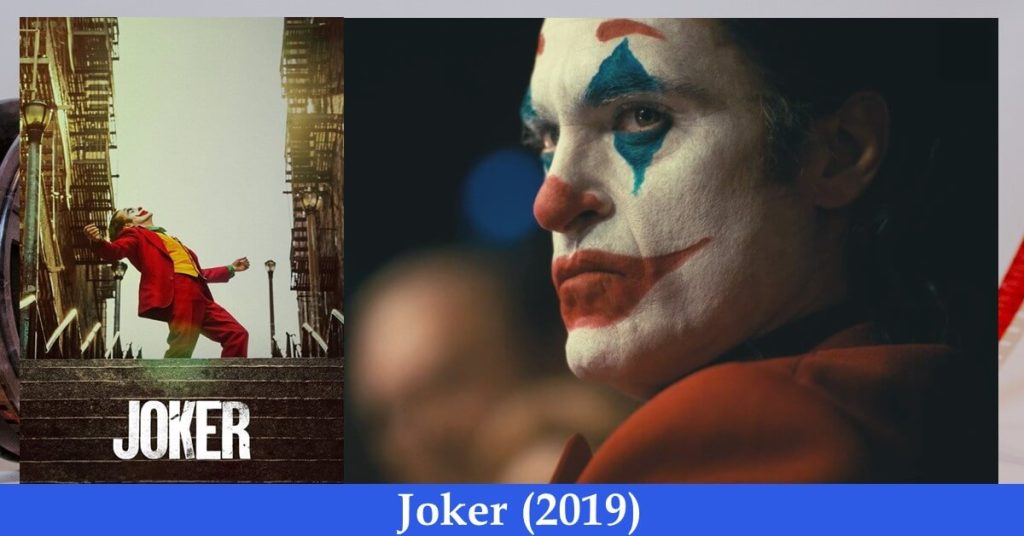

Joker (2019): Todd Phillips’ Joker is an intense character study of a marginalized individual pushed to the edge by systemic failure. The film, like Parasite, dissects the stark contrast between the elite and the impoverished, culminating in a violent uprising.

Us (2019): Jordan Peele’s Us offers a chilling narrative on social division and privilege, using horror as a medium to explore the underbelly of economic inequality.

Conclusion

Bong Joon-ho’s storytelling in Parasite is a testament to his ability to blend genres and deliver powerful social commentary. His use of vertical spaces (the semi-basement, the luxurious house, the hidden bunker) reinforces the rigid class structure.

His abrupt tonal shifts—from comedy to horror to tragedy—mirror the unpredictable nature of economic reality.

With Parasite, Bong does not merely tell a story; he dissects the very fabric of social inequality with scalpel-like precision.

The film is not just about a poor family infiltrating a rich household—it is a parable of modern capitalism, a chilling reminder that, in the end, the true parasite may not be the poor living off the rich, but the system itself, feeding on the hopes and dreams of the less fortunate.