Last updated on May 9th, 2025 at 11:18 pm

Plastic pollution is an ever-growing environmental crisis that has infiltrated almost every corner of our planet. Plastics, synthetic materials derived from petrochemicals, have become an indispensable part of modern life due to their durability, low cost, and versatility.

However, these very attributes make them a catastrophic presence in the environment.

Plastic does not dissolve in water nor does it decay naturally, which means that almost all plastic ever produced still exists in some form. Over time, plastics fragment into microplastics, tiny particles that are easily ingested by marine life and enter the food chain.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme, plastic litter and microplastics are now considered among the most significant environmental threats facing the planet.

Table of Contents

Sources of Plastic Pollution

Plastic pollution originates from multiple sources, including:

Single-use plastics: These include packaging materials, plastic bags, straws, and disposable cutlery. They are designed for convenience but often have a functional life of minutes before being discarded, according to How to Give Up Plastic by Will McCallum.

Industrial and household waste: Plastics from urban areas frequently end up in water bodies due to inadequate waste management systems, as explored in Plastic Soup: An Atlas of Plastic Pollution by Michiel Roscam Abbing.

Fishing and maritime industries: Abandoned fishing nets, also known as “ghost nets,” make up a substantial portion of ocean plastic pollution.

Cosmetics and cleaning products: Many personal care items contain microbeads, which are tiny plastic particles used for exfoliation but ultimately end up in the ocean.

The Global Impact of Plastic Pollution

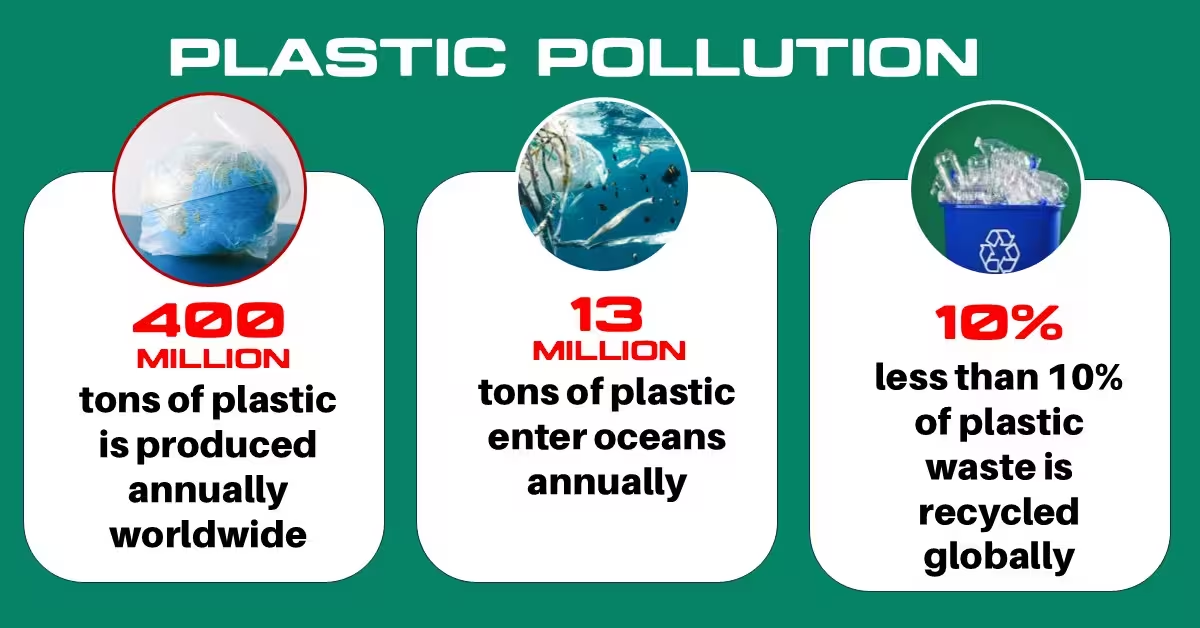

The scale of plastic pollution is staggering:

– By 2050, plastic in the ocean may outweigh fish (Will McCallum)

– Over 1 million plastic bags are used worldwide every minute (Plastic Soup).

– Every year, 13 million metric tons of plastic waste end up in the ocean, affecting marine ecosystems and biodiversity.

The impact is not just environmental but also economic, as countries reliant on fisheries and tourism suffer devastating losses. Plastic pollution contributes to climate change as well—8% of global oil production is used for plastic manufacturing.

A Growing Awareness

The fight against plastic pollution has gained momentum in recent years, largely due to widespread awareness campaigns and scientific research. One of the most pivotal moments in public consciousness came with Blue Planet II, a documentary narrated by my favourite Sir David Attenborough, which showed distressing images of marine animals entangled in plastic waste.

People across the globe have begun recognizing the absurdity of producing materials meant to last for centuries yet designed to be used for mere moments.

According to Will McCallum, “We managed to create a material and use it at an unbelievable scale with no plan for how to deal with it afterwards”.

The Effects of Plastic Pollution on Marine Life

Plastics affect over a thousand marine species through ingestion and entanglement. Among the most disturbing cases:

-Seabirds: Over 90% of seabirds now have plastic in their stomachs (Plastic Soup).

– Turtles: Many mistake floating plastic bags for jellyfish and ingest them, leading to blockages and starvation.

– Whales: Dead whales have been found with stomachs full of plastic, unable to digest or expel the material.

Even in the most remote areas of the planet, microplastics have been found in marine organisms. Scientists have discovered plastic fibers in the deepest parts of the ocean, such as the Mariana Trench (Plastic Soup).

The Human Health Risk

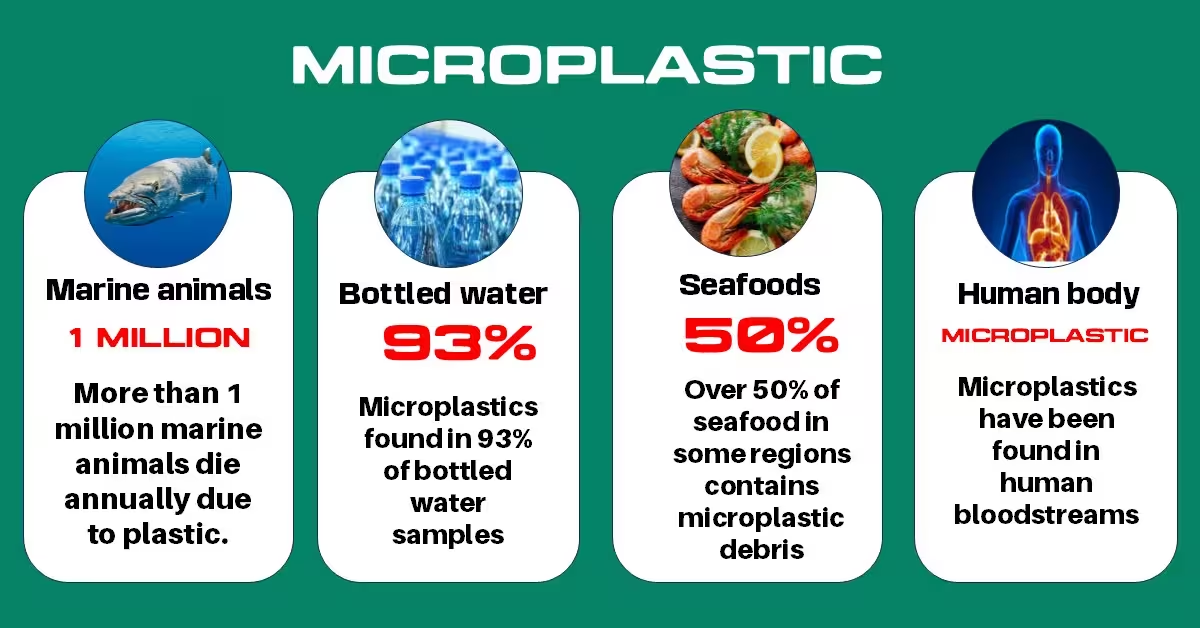

The consequences of plastic pollution extend to human health. Studies have found microplastics in drinking water, seafood, and even human bloodstreams. Plastics contain toxic chemicals like BPA, which have been linked to endocrine disruption and other health issues (Plastic Soup).

The need for urgent intervention has led to global initiatives and policies to curb plastic pollution:

– Plastic bag bans: Bangladesh was the first country to ban thin plastic bags in 2002 after devastating floods worsened by plastic waste (How to Give Up Plastic).

– Microbead bans: Many countries have outlawed microbeads in personal care products due to their harmful impact on marine ecosystems.

– Deposit return schemes: Countries like Germany and Norway have implemented deposit systems for plastic bottles, achieving recycling rates of over 90%.

Plastic pollution is an issue that affects all of us, but it is also one we all have the power to change. As Will McCallum writes, “The problem of plastic pollution is one that affects us all, and therefore one for which we all share responsibility”.

Microplastics: The Invisible Threat

A World Coated in Plastic

Imagine a world where the very air we breathe, the water we drink, and the food we eat is contaminated with microscopic particles—particles so small, yet so dangerous. These are microplastics, a toxic byproduct of our plastic-driven society.

They are everywhere, from the depths of the Mariana Trench to the peak of Mount Everest. Their silent invasion into our ecosystems, bodies, and food chains is an environmental crisis unfolding before our eyes.

Yet, most people are unaware of the sheer magnitude of this problem. Unlike the floating plastic bottles and bags that visibly pollute our oceans, microplastics are invisible, insidious, and far more dangerous. Their presence in our environment is no longer a question—it is a devastating reality.

1. Definition and Scope of Microplastic Pollution

Microplastics are defined as plastic particles smaller than 5 millimeters, often microscopic, that result from the breakdown of larger plastic products or are directly manufactured as tiny particles. These particles originate from countless sources—clothing fibers, car tires, plastic packaging, synthetic cosmetics, and even household dust.

Matt Simon, in his book A Poison Like No Other: How Microplastics Corrupted Our Planet and Our Bodies , presents a haunting revelation: each year, the equivalent of 300 million water bottles worth of microplastics fall on just 6% of U.S. landmass.

Microplastics rain down from the sky, settle in our soil, and seep into our oceans. There is no escape.

These Microplastic particles are categorized into two types:

-Primary microplastics – Manufactured as microbeads in cosmetics, synthetic clothing fibers, or pellets used in plastic production.

-Secondary microplastics – Result from the degradation of larger plastics due to sunlight, wave action, or mechanical wear.

Despite efforts to reduce plastic waste, global production continues to rise, reaching over 300 million tons of plastic annually, (according to The United Nations Environment Assembly, its 400 million tonnes of plastic each year), with only 9% being recycled.

The remaining plastic degrades over time, fragmenting into microplastics, infiltrating the environment, and persisting for centuries.

2. How Microplastics Affect Human Health and Ecosystems

Mohd. Shahnawaz et al in their Microplastic Pollution describe that the real horror of microplastics is not just their omnipresence, but their toxicity. Unlike inert particles, microplastics carry harmful chemicals such as bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and persistent organic pollutants (POPs).

These chemicals mimic hormones, leading to severe health consequences, including infertility, metabolic disorders, and cancer.

3. Microplastics in the Air in Our Water and Foods

Microplastics are not just in water and soil; they are also in the air. Inhaling airborne microplastics can cause respiratory issues, lung inflammation, and even cross the blood-brain barrier. Studies suggest that individuals who work in synthetic textile industries have higher rates of lung diseases and cancers.

Drinking water, whether bottled or tap, is contaminated with microplastics. Shockingly, bottled water contains two times more microplastics than tap water.

Danielle Smith-Llera describes that “Toxic chemicals riding aboard microplastics add secret ingredients to mixing bowls and cooking pots. Bottled water is not plastic-free either—especially when bottled in plastic. In a world study of 11 brands of bottled water, 93 percent of water samples contained microplastics. In one popular brand, as many as 10,000 microplastics were found in each liter-sized bottle.

In seafood, microplastics are now an unavoidable ingredient. Over 28% of fish sampled in Indonesia and 25% in the U.S. contained plastic debris.

A study led by Chelsea M. Rochman tilted Anthropogenic Debris in Seafood found that one-third of seafood sold for human consumption contains plastic debris. The contamination levels are alarming:

– 55% of fish species in Indonesia contained microplastics.

– 67% of fish species in the U.S. had plastic fibers in their digestive systems.

– 33% of shellfish (such as mussels and oysters) contained plastic particles.

Since bivalves like mussels, oysters, and clams are consumed whole, humans ingest the microplastics present in their tissues directly.

Recent research conducted by Danielle Smith-Llera titled You Are Eating Plastic Every Day: What’s in Our Food?” has discovered that even everyday staples like table salt, sugar, and honey contain microplastics. In a study of global sea salt brands, over 90% were found to be contaminated with plastic.

The Environmental Cost

Microplastics disrupt entire ecosystems:

–Marine life suffers – Zooplankton and fish mistake microplastics for food, leading to starvation and bioaccumulation up the food chain.

-Soil contamination – Microplastics alter soil composition, reducing fertility and harming crops.

-Ocean pollution – An estimated 46 billion pounds of microplastics pollute the Atlantic Ocean alone.

Perhaps the most distressing finding is that infants are among the most exposed to microplastic ingestion. Studies show that preparing infant formula in plastic bottles releases millions of microplastic particles per liter.

The evidence is clear—microplastic pollution is one of the most pressing environmental and health crises of our time. We are inhaling, drinking, and eating plastic every single day, and the long-term consequences remain unknown.

In A Poison Like No Other, Matt Simon starkly warns:

“Humanity has fallen into a plasticine progress trap… Without action, by 2100, there could be 50 times the microplastic particles in the ocean than today.”

III. Impact of Plastic on Marine and Aquatic Environments

Plastic pollution is one of the most pressing environmental crises affecting marine and aquatic ecosystems today.

Our oceans, once teeming with vibrant life, now struggle against an ever-growing tide of synthetic waste. Plastic debris, both large and microscopic, infiltrates every level of the marine food web, causing devastating ecological consequences.

This section explores three major aspects of plastic pollution: its effects on marine biota, its impact on oceanic ecosystems, and a case study of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

1. Effects of Plastic on Marine Biota

The following excerpt is drawn from the study Impact of Plastic Waste on the Marine Biota carried by Mohd. Shahnawaz et al. according to their findings, plastic debris, whether in the form of large entangling nets or microplastics, has become a silent killer in our oceans. Marine organisms face two primary threats: entanglement and ingestion.

Entanglement

Marine species like turtles, fish, seabirds, and marine mammals often get trapped in floating plastic debris, leading to severe injuries or even death.

Ghost fishing gear—abandoned fishing nets and lines—accounts for nearly 10% of all marine waste and continues to trap and kill marine creatures long after being discarded.

A study found that 92% of entanglement and ingestion cases in marine wildlifewere linked to plastic waste.

They cite a 2018 huge survey of the 159 coral reefs across Asia-Pacific region showed that over 11.1 billion plastic particles are entangling the corals. However, this number is estimated to increase dramatically 40% by 2025. The authors further stated that out of 124,000 individual reef-building corals, 89% were susceptible to diseases due to plastics, while only 4% were found free from plastic pollution

Ingestion

Marine species mistake plastic particles for food, leading to digestive blockages, malnutrition, and even starvation. Studies have reported plastic debris in over 90% of seabirds’ stomachs.

More than half of the world’s sea turtles have ingested plastic debris. Microplastics also act as carriers for toxic chemicals, accumulating in marine life and entering the human food chain.

The prevalence of plastic in marine biota presents a stark warning: we are poisoning the very ecosystems that sustain us.

In some cases, plastic carries chemical contaminants that lead to bioaccumulation in the food chain. Plastics and the Ocean by Anthony L. Andrady highlights how plastic resin pellets act as “transport mediums for toxic chemicals in the marine environment,” sometimes absorbing pollutants at levels up to one million times higher than the surrounding seawater.

2. Plastic Pollution in Oceans and Its Impact on Marine Ecosystems

The Scale of Plastic Pollution

The book by Carl J. Sindermann titled Ocean Pollution: Effects on Living Resources and Humans and

In the book Plastics and the Ocean by Anthony L. Andrady Plastics from littering and mismanaged waste, transported from land to entering the ocean 8.8 million metric tons per year.

The total amount of plastic debris in our oceans has reached an estimated 250,000 metric tons, according to Anthony L. Andrady. By 2050, plastics in the ocean could outweigh fish if current trends continue.

Microplastics are fragments smaller than 5mm, formed through the degradation of larger plastics. These particles infiltrate every layer of the marine ecosystem, from plankton to whales. More than 50 trillion microplastic particles are estimated to be floating in the ocean.

Disruption of Marine Food Webs

The effects of plastic pollution ripple through the entire marine food web. Microplastics, defined as plastic particles smaller than 5mm, are consumed by plankton, the base of the marine food chain. “We found that in certain oceanic regions, the weight of plastic was six times greater than the weight of zooplankton,” notes a study published in Plastics and the Ocean: Origin, Characterization, Fate, and Impacts.

This imbalance disrupts energy transfer within ecosystems and can lead to population declines in key species. Additionally, microplastics have been found to accumulate toxic chemicals, which can be transferred up the food chain. Studies have documented that fish exposed to microplastics exhibit behavioral changes, reproductive issues, and increased mortality rates (Plastics and the Ocean by Anthony L. Andrady, 2022).

The ingestion of these particles by filter-feeding organisms also threatens the stability of marine populations, reducing biodiversity and altering predator-prey relationships (Ocean Pollution: Effects on Living Resources and Humans, Carl J. Sindermann, 1995). As a result, the entire marine ecosystem faces long-term consequences, impacting not only marine wildlife but also human populations that rely on seafood as a primary food source.

Microplastics absorb toxic chemicals like pesticides and heavy metals, acting as carriers of pollution. Zooplankton, the base of the marine food web, ingest microplastics, which then bioaccumulate up the chain, affecting fish, marine mammals, and eventually humans.

Impact on Coral Reefs

Coral reefs, often called the “rainforests of the sea,” are not immune to plastic pollution. The book Impact of Plastic Waste on the Marine Biota reports that plastic waste increases the risk of coral disease by 20 times. Plastic debris can smother coral, block sunlight, and introduce pathogens that degrade the reef’s structure, threatening the biodiversity that depends on it.

Additionally, plastics act as surfaces for harmful bacterial colonization, including Vibrio species, which are known to cause coral tissue loss and bleaching (Impact of Plastic Waste on the Marine Biota, Mohd. Shahnawaz et al., 2022). Research indicates that over 11 billion plastic items are entangled within coral reefs worldwide, reducing their resilience to climate change.

Coral ecosystems affected by plastic pollution are less capable of recovering from stressors such as rising sea temperatures and ocean acidification, further endangering marine biodiversity.

Studies estimate that coral reefs entangled with plastic have an 89% higher likelihood of disease. The crisis of plastic pollution is not just an ecological disaster—it is an existential threat to marine biodiversity and the health of our planet.

The Persistent Nature of Plastic

Unlike organic materials, plastics do not biodegrade; they fragment into microplastics that persist in the environment for centuries.

These microplastics are carried by ocean currents and have been found in the deepest marine trenches, Arctic ice, and even within marine organisms themselves (Plastics and the Ocean: Origin, Characterization, Fate, and Impacts, Anthony L. Andrady, 2022). Studies suggest that microplastics can alter the behavior, growth, and reproduction of marine species, affecting biodiversity and ecosystem stability (Ocean Pollution: Effects on Living Resources and Humans, Carl J. Sindermann, 1995).

Additionally, plastics in the ocean gradually release toxic additives such as bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates, which can disrupt hormonal functions in marine organisms and pose risks to human health through seafood consumption (Impact of Plastic Waste on the Marine Biota, Mohd. Shahnawaz et al., 2022).

Case Study: The Great Pacific Garbage Patch

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) is the most infamous example of marine plastic accumulation.

Located between Hawaii and California, it spans an area of 1.6 million square kilometers, roughly three times the size of France (Trash Vortex: How Plastic Pollution Is Choking the World’s Oceans, Danielle Smith-Llera, 2018).

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) is one of the most infamous symbols of plastic pollution. Spanning an area twice the size of Texas, this floating mass of plastic debris is not a solid island but a massive soup of microplastics and discarded waste.

The GPGP was first brought to public attention by Captain Charles Moore in 1997, who described the sight as “a soup lightly seasoned with plastic flakes, bulked out here and there with ‘dumplings’ of buoys, net clumps, and crates” (Trash Vortex: How Plastic Pollution Is Choking the World’s Oceans, Danielle Smith-Llera, 2018).

Contrary to popular belief, the patch is not a solid “island” of trash, but rather a high concentration of suspended microplastics interspersed with larger debris.

1. Ecological and Chemical Threats

Marine animals in and around the GPGP are particularly vulnerable. “The microplastics in samples collected from the Pacific Ocean far outweighed plankton,” reports Moore (Trash Vortex: How Plastic Pollution Is Choking the World’s Oceans, Danielle Smith-Llera, 2018).

This contamination directly impacts marine life, leading to widespread ingestion and poisoning. Studies show that over 100,000 marine mammals and more than 1 million seabirds die annually due to plastic pollution, says Danielle Smith-Llera.

Additionally, plastic debris in the GPGP acts as a sponge for persistent organic pollutants (POPs) like DDT and PCBs, which can leach into the tissues of marine organisms. These pollutants can cause hormonal imbalances, immune system suppression, and reproductive issues in marine species, ultimately leading to population declines.

Moreover, the breakdown of plastic in ocean waters releases microplastics, which are ingested by marine organisms at all trophic levels, from zooplankton to apex predators. Recent research indicates that more than 50% of sea turtles and over 90% of seabirds have plastic in their digestive systems. These plastics not only cause internal injuries but also release toxic chemicals that can accumulate in body tissues over time, leading to long-term ecological damage.

Marine animals in and around the GPGP are particularly vulnerable. “The microplastics in samples collected from the Pacific Ocean far outweighed plankton,” reports Moore (Trash Vortex: How Plastic Pollution Is Choking the World’s Oceans, Danielle Smith-Llera, 2018).

This contamination directly impacts marine life, leading to widespread ingestion and poisoning.

Furthermore, research indicates that plastic debris in the GPGP acts as a sponge for persistent organic pollutants (POPs) like DDT and PCBs, which can leach into the tissues of marine organisms

90% of seabirds in the region have plastic in their stomachs.

The devastating impact of plastic on marine environments is undeniable. From entangling and killing marine life to poisoning entire ecosystems, plastic pollution is an urgent crisis that demands immediate action.

The ocean is not just a vast, distant expanse—it is the very lifeblood of our planet. If we do not act now, we may soon find ourselves drowning in a sea of our own making. The choice is ours: to protect and restore our oceans, or to watch them suffocate under the weight of plastic waste.

2. Impact on Freshwater Ecosystems: The Growing Crisis of Microplastics and Pollution

Freshwater ecosystems, once pristine sources of life, are now facing a profound crisis—one that is largely invisible to the naked eye.

Microplastics, minuscule fragments of synthetic materials, are seeping into rivers, lakes, and streams, bringing devastating consequences for both biodiversity and human populations. These emerging contaminants, often overshadowed by larger environmental crises, are now at the forefront of scientific concern.

The consequences of microplastic pollution are multifaceted, impacting everything from tiny aquatic organisms to the very water we drink. As detailed in Freshwater Microplastics: Emerging Environmental Contaminants? by Martin Wagner and Scott Lambert, the implications extend far beyond mere contamination; they disrupt entire ecosystems and threaten human health in ways we are only beginning to understand.

Microplastics and Pollution in Freshwater Ecosystems

Microplastics are defined as plastic particles smaller than 5 mm. They enter freshwater systems through various sources, including:

-Industrial discharges from textile and plastic manufacturing plants.

– Household wastewater carrying synthetic fibers from washing machines.

-Cosmetic products containing microbeads.

-Breakdown of larger plastics due to UV exposure and mechanical degradation.

Studies confirm that these contaminants are present in nearly every freshwater system studied worldwide. Wagner and Lambert (2018) highlight how microplastics persist in the environment, often accumulating in sediments and the digestive systems of aquatic life.

Impact on Aquatic Life

Microplastics pose significant risks to freshwater organisms, particularly those at the base of the food chain:

-Zooplankton and Small Fish: These organisms ingest microplastics, mistaking them for food, leading to malnutrition and growth impairment.

-Bioaccumulation in Larger Species: As small organisms ingest plastics, larger fish consuming them accumulate toxic chemicals, leading to reproductive and neurological damage (Freshwater Microplastics: Emerging Environmental Contaminants? by Martin Wagner and Scott Lambert).

-Chemical Leaching: Many plastics contain harmful additives like phthalates and bisphenol A (BPA), which leach into water and bioaccumulate in aquatic species.

This contamination affects the entire food web, ultimately impacting humans who consume freshwater fish and seafood.

Microplastics in Drinking Water

A particularly alarming consequence of microplastic pollution is its infiltration into drinking water sources. Research from Plastics in the Aquatic Environment – Part II: Stakeholders’ Role Against Pollution reveals that microplastics have been detected in bottled water, tap water, and even groundwater.

The problem is exacerbated by wastewater treatment plants, which are often ineffective in filtering out microplastics. These tiny particles travel through pipelines and reservoirs, ultimately making their way into human consumption.

The health implications are still being studied, but early evidence suggests potential risks such as:

– Gastrointestinal damage from plastic ingestion.

-Hormonal disruptions caused by plastic additives mimicking endocrine signals.

-Potential carcinogenic effects linked to long-term exposure (Plastics in the Aquatic Environment – Part II: Stakeholders’ Role Against Pollution).

Freshwater biodiversity is facing an unprecedented threat due to plastic contamination. Rivers and lakes, which serve as critical habitats for countless species, are turning into microplastic hotspots. Key consequences include:

-Loss of species diversity as microplastics alter food availability and habitat conditions.

-Increased mortality rates among fish, amphibians, and invertebrates due to plastic ingestion and entanglement.

-Chemical pollution amplifying existing environmental stressors, such as climate change and habitat destruction (Plastics in the Aquatic Environment – Part II: Stakeholders’ Role Against Pollution).

The impact of microplastics on freshwater ecosystems is not just an environmental issue—it is a human crisis. From the contamination of drinking water to the collapse of aquatic food webs, the effects are tangible and far-reaching.

We are at a critical juncture. If we fail to act, the silent crisis unfolding beneath the surface of our lakes and rivers will soon reach a point of no return. The time for action is now, before our freshwater ecosystems—and the life they sustain—become irreversibly altered by plastic pollution.

V. Human Health Impacts of Plastic Exposure, Waste Trade, and Chemical Recycling

Plastic is no longer just an environmental issue—it is deeply intertwined with human health. It has invaded our air, water, food, and even our bodies, leading to dire consequences that scientists are only beginning to unravel.

From the microscopic plastic particles we breathe to the toxic waste exported across borders, the human cost of plastic pollution is profound. Even the so-called ‘solutions,’ such as chemical recycling, introduce additional dangers rather than mitigating the crisis. This document delves into these urgent concerns, guided by authoritative sources that reveal the stark realities of plastic’s impact on human health.

1. Health Risks Posed by Plastic Exposure and Contamination

Microplastics have infiltrated every aspect of our lives. Matt Simon in his A Poison Like No Other describes them as an ‘invisible, snowballing crisis’ that has ‘spread like a plague around the world’.

Scientists are finding plastic particles in human lungs, bloodstream, placentas, and even newborns’ first feces. How did we get here? He explains that:

Microplastics are suspended in the air, particularly in indoor spaces. Clothing made from synthetic fibers, such as polyester and nylon, constantly sheds particles, which we unknowingly inhale. Each day, we could be inhaling thousands of microplastics, and even more nanoplastics, which are so small they can cross into our bloodstream.

Autopsies have shown synthetic fibers embedded in lung tissue, raising concerns about chronic inflammation, respiratory diseases, and even cancer (Simon).

Plastics contaminate our food supply, with seafood, table salt, and even bottled water containing alarming levels of microplastic particles.

Infants are the most vulnerable—studies suggest that babies drinking formula from plastic bottles ingest an estimated 1 million microplastic particles per day.

2. Hormonal Disruptors

Many plastics contain endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), such as Bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates, which mimic hormones and interfere with bodily functions.

EDCs are linked to obesity, infertility, developmental disorders, and even cancer.

Children and pregnant women are at heightened risk, as fetal exposure to microplastics could alter hormone function before birth (Simon).

The human body is not equipped to handle the vast influx of plastic it now encounters daily. From lungs to livers, plastic exposure has catastrophic implications for health, many of which remain unknown.

3. Environmental Health Hazards from International Plastic Waste Trade

While wealthier nations pride themselves on ‘recycling,’ much of their plastic waste is shipped to developing countries, where it wreaks havoc on local communities. Nicholas Jay Aulston explores the issue in his International Hazardous Waste Trade how this global waste trade turns marginalized populations into toxic dumping grounds.

He says, “Countries in Southeast Asia and Africa bear the brunt of plastic waste trade, receiving shipments of plastic waste—much of it contaminated and non-recyclable. Plastic waste leaches hazardous chemicals into soil and water, poisoning food supplies and drinking water sources.

Many of these areas lack the infrastructure to manage hazardous waste, resulting in illegal burning, releasing toxic dioxins and furans into the air.

Chronic exposure to burning plastic leads to respiratory diseases, neurological damage, and even cancer. Workers in waste processing facilities, often women and children, suffer from skin diseases, lung infections, and birth defects.

The Basel Convention attempted to restrict hazardous waste trade, yet loopholes allow the continued exploitation of developing nations, writes Aulston.

4. Long-Term Health Consequences of Chemical Recycling

Chemical recycling is often marketed as the future of plastic waste management. However, as Chemical Recycling: A Dangerous Deception by Lee Bell highlights, the process is deeply flawed—environmentally, economically, and most importantly, in terms of human health.

Moreover, chemical recycling produces toxic waste, including dioxins, benzene, and other carcinogens. Facilities release hazardous emissions into the air, particularly affecting nearby communities, often low-income areas already burdened by industrial pollution.

Prolonged exposure to emissions from these facilities is linked to lung disease, cardiovascular problems, immune system disruption, and even neurological disorders.

Workers and local residents face higher cancer risks due to chronic exposure to toxic fumes.

Many facilities lack transparency, making it nearly impossible to track how much pollution is being released into surrounding communities.

Some byproducts, like plastic-derived fuels, are burned, worsening air quality and increasing greenhouse gas emissions (Bell).

Bell argues that chemical recycling is more about public relations than actual environmental progress. Most facilities struggle with inefficiency and high costs—often shutting down after failing to meet their recycling goals. Instead of solving the plastic crisis, chemical recycling perpetuates fossil fuel dependency and generates even more pollution.

Plastic pollution is not just an environmental issue—it is a direct and devastating threat to human health. Microplastics infiltrate our lungs, bloodstream, and food. The international waste trade exploits vulnerable communities, leaving them with toxic consequences. And chemical recycling, rather than solving these issues, creates new hazards.

VI. Plastic Waste and Global Trade

Plastic waste is no longer just an environmental issue; it is a global crisis interwoven with economic, geopolitical, and social injustices.

The trade of plastic waste, mainly from developed nations to developing countries, has long been a silent but devastating extension of modern colonialism. Countries that generate the most plastic waste, particularly in the Global North, have found ways to export their waste burdens to nations in the Global South, exacerbating environmental degradation and perpetuating socio-economic inequalities.

This section examines the economic and geopolitical dynamics of plastic waste trade and how it fuels environmental injustices.

Drawing on insights from Sedat Gündoğdu’s Plastic Waste Trade: A New Colonialist Means of Pollution Transfer and Gerry Nagtzaam et al.’s Global Plastic Pollution and Its Regulation, we explore how plastic waste trade has become an exploitative economic system and how it disproportionately impacts vulnerable communities.

1. The Global Plastic Waste Market: A Lucrative but Dangerous Business

The global plastic trade has become a billion-dollar and a lucrative but dangerous businessindustry, with high-income countries, particularly the United States, European Union, Japan, and Canada, exporting millions of tons of plastic waste annually to developing nations such as Malaysia, Indonesia, Turkey, and Vietnam (Gündoğdu, 2024).

The plastic waste market operates under the guise of recycling, but much of the exported waste is not recyclable. Instead, it ends up in landfills, rivers, or is openly burned, releasing hazardous chemicals.

China’s National Sword policy (2018), which banned plastic waste imports, forced exporters to divert shipments to Southeast Asia and other vulnerable regions, leading to further environmental and economic instability (Nagtzaam et al., 2023).

2. Economic Exploitation

The term “waste colonialism”, coined in 1989 during discussions on the Basel Convention, describes the way high-income nations offload their environmental burdens onto economically weaker states (Gündoğdu, 2024).

Gündoğdu posits that the economic justification for importing plastic waste in developing countries is often linked to job creation and industrial demand. However, the reality is starkly different—most plastic waste is unprocessable, leading to hazardous working conditions and severe environmental degradation.

For example, Turkey, after China’s ban, becomes one of the largest importers of plastic waste from Europe. By 2020, over 600,000 tons of plastic waste were shipped to Turkey, much of it illegally disposed of, polluting rivers and farmlands (Gündoğdu & Walker, 2021).

Despite international treaties such as the Basel Convention, loopholes allow plastic waste trade to continue under “recyclable material” classifications.

Wealthier nations have used economic leverage to pressure developing countries into accepting plastic waste, often under the pretext of economic aid or trade agreements.

According to Gündoğdu (2024), much of the plastic waste sent to the Global South contains hazardous materials, including polyvinyl chloride (PVC), brominated flame retardants, and heavy metals.

The UNEP (2021) reported that 70% of exported plastic waste is mismanaged, leading to contamination of water bodies and agricultural lands.

Additionally, countries like Malaysia and Indonesia have started rejecting shipments of contaminated plastic waste, sending them back to origin nations, creating diplomatic tensions (Nagtzaam et al., 2023).

Informal recycling sectors often resort to open burning, exposing workers and nearby communities to toxic fumes, carcinogens, and respiratory diseases. Most workers in the plastic waste sector belong to low-income, marginalized communities with little regulatory protection.

The case Study in Indonesia’s Plastic Waste Crisis by Yuyun Ismawati et al. (2023) found that plastic waste dumped in Indonesia often contains household waste from European and American cities, forcing local communities to manage it without proper infrastructure.

Not only that, the gender disparity between women and children are disproportionately affected, often employed in hazardous sorting jobs for minimal wages.

Illegal dumping and burning of plastic waste contribute environmental catastrophe including contaminated lands and oceans with microplastics entering soil, rivers, and even the food chain. The Mediterranean Sea has seen rising plastic pollution due to Turkey’s increasing role as a plastic waste hub (Gündoğdu & Walker, 2021), over 1 million marine animals die annually due to plastic pollution, much of it originating from mismanaged waste in developing countries (UNEP, 2022).

The global plastic waste trade represents a modern extension of colonialist exploitation, where the wealthiest nations push their environmental burdens onto the world’s most vulnerable populations. The economic and geopolitical forces behind this trade make it difficult to dismantle, but urgent action is necessary to prevent further damage.

International cooperation, strict regulatory frameworks, and sustainable waste management practices are crucial to ending this cycle of pollution and injustice.

VII. Plastic Waste Management and Recycling: Myths and Realities

Plastic has woven itself into the fabric of modern life. It is lightweight, durable, and inexpensive—attributes that have propelled its mass adoption across industries.

However, these same properties make plastic pollution a formidable environmental challenge. Despite increasing global efforts toward recycling and waste management, plastic waste continues to accumulate at alarming rates.

This part critically examines the limitations of current plastic recycling methods, the promises and pitfalls of chemical recycling, and sustainable alternatives for managing plastic waste.

1. Limitations of Current Plastic Recycling Methods

The popular belief that plastics are easily recyclable is a widespread misconception. In reality, the limitations of traditional recycling methods have led to only a fraction of plastic waste being effectively reused.

Recycling plastic is far from a perfect system. As highlighted in Chemical Recycling: A Dangerous Deception, less than 10% of plastic waste is actually recycled globally. Conventional mechanical recycling—where plastic waste is shredded, melted, and reformed—faces multiple challenges:

-Quality Degradation: Plastics lose structural integrity after multiple recycling cycles, making them unsuitable for reuse in high-quality products.

-Complexity of Plastic Types: With thousands of different plastic resins, sorting and processing them efficiently remains a technological and economic barrier.

– Contamination Issues: Food residues, dyes, and mixed polymers often render a significant portion of plastic waste non-recyclable.

-Economic Viability: Virgin plastic is often cheaper to produce than recycled plastic, reducing market incentives for recycling.

A stark example of the failures of conventional recycling comes from the U.S. EPA, which found that plastic accounted for only 12% of municipal solid waste in 2018, despite decades of recycling efforts. The lack of infrastructure, consumer awareness, and economic incentives have contributed to this dismal rate.

Plastics were introduced under the pretense of a sustainable circular economy, but in practice, most end up in landfills or incinerators. According to Plastic Pollution Challenges and Green Solutions, marine plastic pollution is escalating, causing severe harm to aquatic ecosystems and biodiversity. Moreover, microplastics have been detected in human blood, lung tissue, and even cardiovascular plaque, raising serious health concerns.

2. Chemical Recycling: Solution or False Hope?

Chemical recycling—also marketed as “advanced recycling”—claims to break plastic down into its molecular components, allowing for its repurposing into new plastic or fuel.

While proponents argue that this method offers a sustainable solution, critics warn that it is more of an industry greenwashing tactic than an effective fix.

Chemical recycling is a dangerous deception that makes it clear that chemical recycling is highly energy-intensive and contributes significantly to climate change. Processes like pyrolysis and gasification require extreme temperatures, leading to large amounts of greenhouse gas emissions and toxic byproducts.

A case study of the Brightmark Energy facility in Indiana illustrates the flaws of chemical recycling. The plant promised to process 100,000 tons of plastic waste annually but managed to recycle only 2,000 tons before facing technical failures, fires, and safety complaints.

Rather than reducing plastic waste, chemical recycling generates new environmental hazards:

– Releases persistent organic pollutants (POPs), which remain in the environment for decades.

– Produces large quantities of hazardous byproducts, which require separate disposal.

– Many facilities ultimately burn plastic-derived oils as fuel, leading to further CO2 emissions.

In summary, chemical recycling does not create a closed-loop system for plastics. Instead, it serves as an excuse to continue plastic production without addressing the root causes of waste.

Given the inadequacy of current recycling efforts, what real solutions exist? Plastic Pollution Challenges and Green Solutions suggests multiple pathways for reducing plastic waste effectively.

One of the most promising solutions is the development of biodegradable and compostable plastics. Research suggests that bioplastics derived from plant-based sources could replace traditional plastics in many applications. However, these alternatives require proper industrial composting facilities, which are still lacking in many countries.

Manufacturers must be held accountable for the full lifecycle of plastic products. Countries such as Germany and Canada have implemented Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) programs, requiring companies to finance waste management systems for their plastic products.

Cities like Indore and Panaji in India have successfully adopted smart waste management technologies, using IoT-enabled tracking and localized recycling ecosystems to improve plastic collection efficiency.

However, reducing plastic waste is not just a technological challenge but also a behavioral one. Campaigns like “No Plastic” movements, bans on single-use plastics, and eco-conscious packaging initiatives have demonstrated significant impact when implemented effectively.

The myth of efficient plastic recycling has been largely debunked. Mechanical recycling is fraught with inefficiencies, and chemical recycling, despite being marketed as a solution, is an unsustainable and polluting process. Instead, we must embrace a multi-faceted approach: investing in biodegradable materials, enforcing producer responsibility, modernizing waste management, and changing consumer habits. Without a radical shift in how we produce and consume plastic, the global waste crisis will only deepen.

By looking beyond industry-driven narratives and embracing real solutions, we can create a future where plastic waste is no longer an insurmountable problem, but a challenge overcome through innovation and collective action.

VIII. Policy and Governance: Tackling Plastic Pollution

Plastic pollution is one of the defining environmental crises of our time. The proliferation of plastic, from packaging to microplastics infiltrating our food and water, threatens ecosystems, human health, and economic stability.

Despite its convenience and versatility, plastic has a dark side—one that has persisted for decades with little regulatory success. Addressing this issue requires not just incremental changes but systemic shifts in governance, industry practices, and consumer behavior.

Here we will explore the historical and current efforts to regulate plastic use, as well as forward-thinking policy recommendations. Insights are drawn from Global Plastic Pollution and Its Regulation by Gerry Nagtzaam et al. and Plastic Pollution: Nature-Based Solutions and Effective Governance by Gail Krantzberg et al., both of which provide a comprehensive understanding of plastic governance, legal challenges, and possible solutions.

1. Historical and Current Efforts to Regulate Plastic Use

The first significant national policy regulating plastic waste did not emerge until the 1990s, when Denmark implemented a plastic bag levy (Nagtzaam et al.). This marked a turning point in government recognition of the issue.

Before this, plastic pollution had been largely ignored or treated as an unavoidable consequence of industrial progress.

In the early 2000s, outright bans on certain plastic products gained traction, especially single-use plastic bags and microbeads.

Countries such as Bangladesh, Kenya, and the European Union led the way in phasing out harmful plastics. However, these bans were met with significant resistance from industries that profit from disposable plastics.

Despite the increasing awareness of plastic’s environmental harm, legal and regulatory responses remain fragmented.

As Nagtzaam et al. point out, “Policy regulation on sustainable plastic management lagged the creation of plastic for several decades, with the first serious national approach only appearing in the 1990s”. The industry’s lobbying efforts have also hampered progress, particularly in nations with powerful petrochemical sectors, such as the United States.

While some nations have moved forward with extended producer responsibility (EPR) programs, most global efforts remain voluntary or weakly enforced. The Basel Convention’s 2019 amendment restricting plastic waste exports was an important milestone, yet enforcement remains an issue.

Scientific assessments have played a crucial role in shaping policy. As Nagtzaam et al. highlight, “By updating initial assessments and creating indicators to monitor progress, scientists can help properly modify stakeholder strategies in response to the successes or failures of policies adopted within environmental regimes” (p. 296).

However, a lack of unified international scientific standards for plastic impact assessments still hinders cohesive regulatory action.

2. Policy Recommendations and Future Steps

1. Strengthening Global Agreements

A legally binding global treaty on plastics is urgently needed. As Krantzberg et al. emphasize, “Plastic waste is a complex problem and needs to be addressed more holistically… including better designs, sustainable feedstocks, and partnerships between industry, researchers, and policymakers”. A robust treaty must include:

– Mandatory reduction targets for virgin plastic production.

– Standardized reporting and monitoring systems to track plastic waste generation and disposal.

– Enforceable penalties for non-compliance, unlike many current voluntary frameworks.

Governments must shift away from a linear “take-make-dispose” model toward a circular economy where plastics are designed for reuse and recycling. Krantzberg et al. note that “Instead of cradle-to-grave, the new designs should focus on cradle-to-cradle”.

To achieve this standardized packaging regulations should be established to ensure materials are reusable or recyclable; investment in innovative materials such as biodegradable and compostable plastics should be increased; and stronger EPR policies should require companies to take full responsibility for plastic waste.

Economic measures can be powerful tools for reducing plastic pollution. Based on historical success stories like Ireland’s plastic bag tax, experts advocate for:

– Plastic taxes at both production and consumption levels (Nagtzaam et al.).

– Subsidies for businesses that use alternative materials, helping to drive demand for sustainable options.

– Bans on fossil-fuel subsidies that artificially lower plastic prices and encourage overproduction.

The failure of existing recycling systems is well-documented. Krantzberg et al. argue that “a truly effective response requires that policymakers and industries rethink how plastics are collected and processed”. Solutions include:

– Investment in “smart recycling” technologies that improve waste separation.

– Mandated minimum recycled content in new plastic products.

– International cooperation on plastic waste trade regulations to prevent illegal dumping in developing nations.

2. Education and Public Engagement

Public perception plays a crucial role in shifting policy. Campaigns like Earth Day’s “End Plastic Pollution” initiative, demonstrate how grassroots activism can push governments toward stronger action.

As Nagtzaam et al. emphasize, “Expanding this information campaign infrastructure on an international scale is crucial for creating informed and engaged environmental stewards”.

Public engagement efforts should include:

– Educational campaigns to inform consumers about the impact of plastics.

– Community-based cleanup initiatives that connect local action to global solutions.

– Citizen science programs that empower people to contribute to research on plastic pollution.

Plastic pollution is not just an environmental issue—it is a governance crisis, an economic challenge, and a social responsibility.

We must recognize that tackling plastic pollution is about more than bans and taxes; it requires a fundamental shift in how societies produce, consume, and dispose of materials.

A global treaty on plastics, strong national regulatory frameworks, and corporate accountability measures are necessary to address this crisis effectively.

As Krantzberg et al. conclude, “The main message is that plastic waste is a complex problem and needs to be addressed more holistically”. It is time for policymakers, industries, and individuals to take bold action—before we are buried under our own waste.

9. Activism and Global Movements: Combating Plastic Pollution

Plastic pollution is one of the most pressing environmental crises of our time. Activists, scientists, and community leaders worldwide have stepped up to challenge corporations, change policies, and shift consumer behaviors.

Activism plays a crucial role in creating awareness, pushing for legislative changes, and inspiring grassroots movements.

1. Raising Awareness and Challenging the Status Quo

Marcus Eriksen, in Junk Raft: An Ocean Voyage and a Rising Tide of Activism to Fight Plastic Pollution, highlights how activism has been instrumental in exposing the devastating effects of plastic pollution.

Eriksen himself undertook a harrowing journey across the Pacific on a raft made of 15,000 plastic bottles to bring attention to the floating plastic debris accumulating in ocean gyres. His expedition revealed that “science in this synthetic century avoided the question, ‘Where is away?’” stressing that plastic waste has no true end destination but continues to pollute ecosystems worldwide.

Activism has also played a critical role in revealing the recycling myth. Many people assume that plastic waste is efficiently recycled, but Eriksen notes that “most plastic waste is either incinerated or dumped, with less than 9% being effectively recycled”.

These revelations have led to movements that demand accountability from corporations and governments.

2. Grassroots Movements and Policy Change

Lucy Siegle, in Turning the Tide on Plastic, describes how grassroots activism has forced changes at both local and global levels.

She discusses how local activists have led campaigns that resulted in bans on single-use plastics and microbeads. “Boycotting single-use plastic is also taking a stand against new oil exploration and extraction – a double high-five for the planet”.

One striking example is the Plastic-Free July campaign, which started as a small initiative in Australia but has grown into a global movement inspiring millions to reduce their plastic use.

Similarly, beach clean-up events have not only removed thousands of tons of plastic from coastlines but have also become powerful symbols of public resistance against plastic pollution.

Governments, NGOs, and international organizations have implemented policies and strategies to reduce plastic waste. These efforts are crucial, as Eriksen points out that “global plastic production is expected to exceed a billion tons annually by 2050 unless radical change happens”.

3. Corporate Responsibility and Sustainable Packaging

Many corporations, pressured by activist groups, have pledged to reduce their plastic footprint. Brands such as Unilever and Nestlé have committed to eliminating unnecessary plastic packaging, while others have introduced refill and reuse systems.

However, Siegle argues that true progress will only come when companies move beyond greenwashing and implement tangible changes: “We cannot simply pick our way out of the problem; solutions must be systemic”.

4. Policy Interventions and Bans

Governments worldwide have enacted policies to curb plastic consumption:

– The European Union has banned single-use plastics like cutlery, plates, and straws.

– Kenya has one of the strictest plastic bag bans, with severe penalties for violators.

– India has pledged to phase out single-use plastics by 2025.

– Canada has introduced a ban on plastic checkout bags, straws, and six-pack rings.

The effectiveness of these measures is mixed, but they indicate growing global recognition of the plastic crisis and the need for urgent action.

United Nations Initiatives to Address Plastic Pollution

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has been at the forefront of international efforts to combat plastic pollution. The UNEP Annual Report 2024 outlines multiple initiatives aimed at tackling the crisis.

At the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA-6), over 170 countries agreed to negotiate a legally binding treaty to end plastic pollution. The treaty aims to:

– Reduce plastic production at the source.

– Implement circular economy principles.

– Establish global guidelines on plastic waste management.

UNEP Executive Director Inger Andersen stated, “We must work towards agreeing on a strong instrument to end plastic pollution before UNEA-7”.

Launched by UNEP, the Clean Seas Campaign has engaged over 60 countries in reducing marine plastic pollution. Countries participating in the initiative have introduced bans on microplastics in cosmetics and improved waste management systems, according to UNEP Annual Report 2024.

The UNEP report highlights that US$12 billion has been committed to land restoration and pollution control through the Riyadh Action Agenda.

Moreover, UNEP has been conducting extensive research on the impact of plastic pollution on biodiversity, human health, and climate change.

5. The Power of Collective Action

Activism, policy reforms, and global initiatives are shaping the fight against plastic pollution. While significant progress has been made, much remains to be done. The work of activists like Marcus Eriksen, the initiatives described by Lucy Siegle, and UNEP’s global actions remind us that tackling plastic pollution requires collective effort, innovation, and systemic change.

As Eriksen puts it, “We need zero-waste and end-of-life design for everything we create; a world in which social and environmental justice becomes part of product and systems design”.

It is up to us, as individuals and as a global community, to turn the tide on plastic and protect our planet for future generations.

10. Transforming the Future of Plastic

For decades, humanity has been trapped in a cycle of plastic dependency—one that has brought undeniable convenience but also devastating consequences for our planet.

The transition from a “Plastic Age” defined by waste to one that embraces sustainability is both urgent and necessary.

Albert Bates, in Transforming Plastic: From Pollution to Evolution, describes the exponential growth of plastic waste, noting that “today, the equivalent of five grocery bags of plastic trash piles up behind every foot of coastline on the planet” (Bates). This stark reality highlights that our reliance on plastic has not just left a mark—it has reshaped ecosystems and is endangering marine life at unprecedented rates.

However, transformation is possible. The evolution of plastic usage must focus on redefining materials, redesigning consumption patterns, and rethinking disposal systems. Instead of treating plastic as a disposable commodity, we must innovate towards biodegradable, reusable, and circular solutions. Bates emphasizes that industries must “design new products that degrade under natural conditions,” particularly for packaging, which constitutes the largest stream of plastic waste (Bates).

Solutions such as bioplastics, recycling reforms, and corporate accountability must be implemented to slow the production of new plastic and close the loop on existing waste.

The shift from pollution to evolution is not just an ecological necessity but a societal responsibility. Just as the Industrial Revolution reshaped economies, the “Plastic Revolution” of the future must reshape consumer habits, corporate policies, and governmental regulations to establish a sustainable global model.

1. How Individuals Can Contribute to Reducing Plastic Waste

Many feel powerless in the face of such a colossal issue, but the truth is that individuals have the potential to drive systemic change.

Will McCallum, in How to Give Up Plastic, states: “If you take one message from this book, it is this: the problem of plastic pollution affects us all, and therefore we all share responsibility as individuals, but more importantly, collectively” (McCallum). It is in our daily choices that we can make the greatest impact.

Practical Steps for Individuals:

1. Refuse Single-Use Plastics:

Avoid plastic straws, bags, and cutlery. McCallum notes that “500 million plastic straws are used every single day in the United States alone” (McCallum). Opting for reusable alternatives makes a tangible difference.

2. Adopt a Refillable Lifestyle:

Use stainless steel or glass bottles, bring reusable shopping bags, and store food in non-plastic containers. McCallum emphasizes that “less than half of the 13 billion plastic bottles thrown away each year in the UK are recycled” (McCallum).

3. Support Legislative and Corporate Change:

Engage with policymakers to implement plastic bans and deposit return schemes. In Scotland, a deposit return scheme for bottles has recaptured over 90% of plastic waste, proving such initiatives work (McCallum).

4. Educate and Influence Others:

Share knowledge with friends, family, and social circles. Advocacy is essential in pushing corporations and governments toward stricter regulations.

5. Participate in Cleanup Initiatives:

Volunteer for beach and community clean-ups. Even small-scale efforts contribute to raising awareness and reducing local pollution.

A Future Without Plastic Waste?

Despite the overwhelming scale of plastic pollution, both Bates and McCallum provide hopeful perspectives: change is not only necessary but achievable. The technological advancements in biodegradable alternatives, corporate responsibility policies, and global legislative efforts suggest that transformation is underway.

Bates urges a fundamental shift in how we view plastic, stating: “Plastics are a problem for our culture… but whether the Plastic Age can be shortened and made friendlier is entirely within our control” (Bates). Meanwhile, McCallum encourages activism, writing that “the greatest changes are not driven by governments or businesses, but by the collective actions of individuals” (McCallum).

The future of plastic will not be dictated solely by scientists, governments, or corporations—it will be determined by each of us, in the choices we make every day.

Moving from a culture of waste to a culture of sustainability is not just an environmental necessity; it is a testament to human innovation and resilience.

The world stands at a crucial juncture—will we continue perpetuating plastic waste colonialism, or will we take responsibility for the waste we create? The answer lies in immediate and collective action

The time to act is now. The world cannot afford to wait another generation to tackle the plastic crisis. If each person takes responsibility, we can truly transform plastic from pollution to evolution.

Works/book cited

- 1. Ahamad, Arif, Pardeep Singh, and Dhanesh Tiwary. Plastic and Microplastic in the Environment: Management and Health Risks.

- 2. Andrady, Anthony L., ed. Plastics and the Ocean: Origin, Characterization, Fate, and Impacts. North Carolina, USA.

- 3. Arias, Andrés Hugo, ed. Coastal and Deep Ocean Pollution.

- 4. Aulston, Nicholas Jay. International Hazardous Waste Trade: Human and Environmental Health Impacts.

- 5. Bates, Albert. Transforming Plastic: From Pollution to Evolution.

- 6. Bell, Lee, and IPEN. Chemical Recycling: A Dangerous Deception—Why Chemical Recycling Won’t Solve the Plastic Pollution Problem.

- 7. Eriksen, Marcus. Junk Raft: An Ocean Voyage and a Rising Tide of Activism to Fight Plastic Pollution.

- 8. Farrelly, Trisia, Sy Taffel, and Ian Shaw, eds. Plastic Legacies: Pollution, Persistence, and Politics.

- 9. Goel, Malti, and Neha G. Tripathi, eds. Plastic Pollution: Challenges and Green Solutions.

- 10. Gray, Tracey. Ocean of Plastic.

- 11. Gündoğdu, Sedat, ed. Plastic Waste Trade: A New Colonialist Means of Pollution Transfer.

- 12. Hasanzadeh, Rezgar, and Parisa Mojaver, eds. Plastic Waste Treatment and Management.

- 13. Karatzas, Elena, et al. Global Plastic Pollution and Its Regulation: History, Trends, Perspectives.

- 14. Krantzberg, Gail, and Sandhya Babel. Plastic Pollution: Nature-Based Solutions and Effective Governance.

- 15. McCallum, Will. How to Give Up Plastic: A Guide to Changing the World, One Plastic Bottle at a Time.

- 16. Nagtzaam, Gerry, Geert Van Calster, Steve Kourabas, and Elena Karataeva. Global Plastic Pollution and Its Regulation: History, Trends, Perspectives.

- 17. Rochman, Chelsea M., et al. Anthropogenic Debris in Seafood: Plastic Debris and Fibers from Textiles in Fish and Bivalves Sold for Human Consumption.

- 18. Roscam Abbing, Michiel. Plastic Soup: An Atlas of Plastic Pollution.

- 19. Shahnawaz, Mohd., Charles Oluwaseun Adetunji, Mudasir Ahmad Dar, and Daochen Zhu, eds. Microplastic Pollution.

- 20. Shahnawaz, Mohd., Manisha K. Sangale, Zhu Daochen, and Avinash B. Ade, eds. Impact of Plastic Waste on the Marine Biota.

- 21. Siegle, Lucy. Turning the Tide on Plastic.

- 22. Simon, Matt. A Poison Like No Other: How Microplastics Corrupted Our Planet and Our Bodies.

- 23. Sindermann, Carl J. Ocean Pollution: Effects on Living Resources and Humans.

- 24. Sin, Lee Tin, and Bee Soo Tueen. Microplastics Pollution and Worldwide Policies on Plastic Use.

- 25. Smith-Llera, Danielle. Trash Vortex: How Plastic Pollution Is Choking the World’s Oceans.

- 26. Smith-Llera, Danielle. You Are Eating Plastic Every Day: What’s in Our Food?

- 27. United Nations Environment Assembly. We Are All in This Together.

- 28. Wagner, Martin, and Scott Lambert, eds. Freshwater Microplastics: Emerging Environmental Contaminants?