Last updated on October 31st, 2023 at 08:09 pm

The recent and sudden spark of the ‘Safe Road Movement’ in Bangladesh by the student protests across the country demanding ‘Safe Road’ speak volumes about the faulty rules and regulations not only in the Traffic Sector but the entire ambit of the rule of law as well, which is riddled with corruption, acrimony, anomalies, cronyism, unscrupulous lawmakers, inability to enforce the law without political consideration.

Background

Safe Road movement in Bangladesh

Began on July 29, 2018, across the country protests and processions paralyzed the country as far-plunged bus services were suspended by the drivers and owners. Students from high school levels to university level all got themselves involved with the movement of ‘Road traffic safety’ and continued until the Government’s intention to reform traffic laws to make the road safe by awarding proper punishment to the guilty drivers.

Nearly 18 million students from the school, college and university staged the protestation after the gory road accident that killed 2 students on the spot and injured nine other students of Shaheed Ramiz Uddin Cantonment College on the airport road of Dhaka, on July 29, 2018. In 2019, during the two Eid vacations and in a span of just three months 273 people died from 232 road traffic incidences injuring 849 others, in Bangladesh. Between July 3 and July 17, at least 398 people were killed and twice the number have been injured. In a month as many as 739 people were killed and 2042 were injured in the country in July 2022, according to another report.

Time again innocent pedestrians are being killed, injured and maimed and time again some students with a sense of urgency for ‘Safe Road’ take the street only to return with empty buzz words from the authority. Drivers are not punished as expected, and proper licensing and stance for vehicular fitness have never been taken.

The second phase of protestation for ‘Safe Road’ began by the university students as a passenger bus ran over and killed a student of Bangladesh University of Professionals on March 20, 2019, while he was crossing the road. The bus was reportedly in competition with another bus from the same company: Suprobhat Paribahan. According to reports, at least 4,439 people were killed in 3,103 incidences in Bangladesh in 2018 alone.

According to the Annual Road Accident Report 2019, the Shipping and Communication Reporters’ Forum (SCRF) revealed that road-traffic casualties claimed 4,628 lives in 2019 and the news reports it to be 5,227. Moreover, 6,685 people died and 8,600 people were injured in 2020. Even amid the Coronavirus epidemic, traffic-related deaths kept increasing.

Citizens and the city-dwellers too must own the blame of traffic casualties. Irresponsible jaywalking, ignoring traffic rules, not using footbridges and zebra crossing, proper stoppages for boarding and taking the wrong sites are also responsible for frequent traffic casualties. Is it the ‘Safe Road’ or ‘Safe Life’ we must speak about?

Road traffic fatality report

Academics at McGill University, in Montreal in 2016 found “numerous factors contribute to road traffic fatalities, human factors are implicated to some degree in an estimated 89 % of crashes. Human factors that impair the ability for safe driving include alcohol intake (driving while impaired by alcohol), fatigue and sleep deprivation, distracted driving by cell phones and passengers’ characteristics. Different empirical and theoretical approaches have been taken to understand the underpinnings of Road Traffic Crashes. Like Iversen, another researcher found that people who had been involved in at least one Road Traffic Crashes over the past one year have reported more speeding, reckless driving, and driving while impaired over the same period than those without RTCs over the past year”.1

In addition to that, unskilled driving, underaged handling of motor vehicles, completion of making multiple trips in a view to maximise wage, lack of proper training facilities, traffic police extortion on the road, over speeding, “medicinal or recreational drugs, fatigue, human tolerance factors crash-helmets not worn by users of two-wheeled vehicles, insufficient vehicle crash protection for occupants and for those hit by vehicles”2, risky driving by young drivers, sensation-seeking motor operating, alcohol consumption and drivers’ psychological trait cannot be underestimated. The followings are tittle detailed explanations by researchers of some of the most common risk factors to Traffic Road fatality.

Common risk factors for road traffic fatality

1 . Risky driving by young drivers: Risky driving behaviour includes aggressive driving, speeding, and rule violations. Among these, speeding was the most common behaviour and an important contributor to Road Traffic Crashes.

The association between youthful age and Road Traffic Crashes have been attributed to inexperience. Young drivers are more frequently involved in Road Traffic Crashes and road fatalities than older drivers. Young drivers are overrepresented in Road Traffic Crashes and their resulting fatalities and injuries. Globally, young drivers below 34 years old were involved in 45% of fatal crashes, 50% of injuries and 49% of property-damage resulting from Road Traffic Crashes in 2001.1

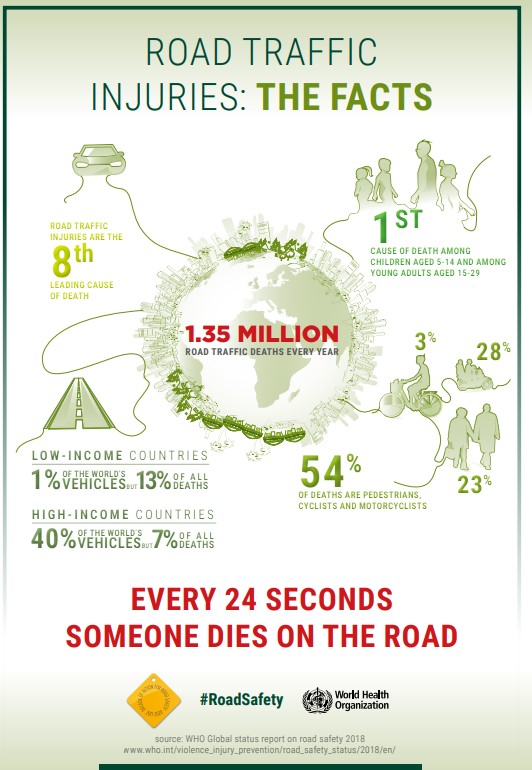

According to WHO, 1.35 million road traffic deaths occur every year. Number 1 those died aged 15-29 years.

Another study conducted by the British Psychological Society, Brisbane, Australia says that “Novice drivers in motorised countries are typically adolescents. They have a disproportionately high rate of involvement in road crashes, a phenomenon that remains even in the context of steadily-reducing crash rates for all drivers in recent years.

Research undertaken within countries that are members of the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) has also shown that for each young driver fatally injured in a crash, another 1.3 persons on average are killed as a result of the crash. Young novice drivers are also influenced by the attitudes and behaviours of their parents and their peers. Specifically, risky driving modelled by parents is likely to be imitated by the young novice, and young drivers report feeling pressured to comply with requests to undertake risky behaviour by their peer passengers.3

2. Sensation seeking motor operating: Sensation seeking has been linked to a range of different risk-taking driving behaviours that is also responsible for Road Traffic Crashes. For example speeding, drunk driving, and Road Traffic Crashes have been associated with increased sensation-seeking scores. Similarly, impulsivity has been consistently identified as an important factor in risky driving behaviours, including drink-driving.

Sensation-seeking and impulsivity characteristics both appear to have a biological basis. For example, high sensation seekers showed stronger fMRI (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) responses to high-arousal stimuli in brain regions (insula, posterior medial orbitofrontal and prefrontal cortex) associated with arousal and reinforcement compared to low sensation seekers.3

Neuroimaging studies on impulsivity reveal the involvement of the prefrontal cortex insula, anterior cingulate cortex, and amygdala. These areas of the brain, particularly the prefrontal cortex, are involved in executive functioning. Indeed, patients with brain injuries or pathologies affecting the prefrontal cortex have shown a tendency for riskier decision-making and a disregard for the negative consequences of their actions”.

This sensation-seeking or “sensitivity to reward behaviour” amplify, “risky driving behaviour” is associated with a range of potential rewards which can impact upon road safety. Of particular concern for the young novice driver is experiencing strong desirable emotions. These feelings include excitement and power, and they have consistently been found to be associated with risky driving, offences and crashes.2

3. Alcohol consumption: “The operation of a motor vehicle requires the integration and evaluation of multiple sources of cognitive and behavioural information to guide appropriate decision making and driving behaviour. Executive and psychomotor (relating to the movement or muscular activity with mental processes), functions are inter-related and intimately connected with the intact function of the brain.

Executive function is defined as a group of cognitive skills responsible for the implementation of purposeful, goal-directed behaviours such as inhibition, cognitive flexibility, 23 working memory, and planning. The psychomotor function is the relationship between executive functions and physical movements such as coordination, manipulation, dexterity, strength, speed, and fine motor skills.

Alcohol intake significantly affects the frontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, insula and cerebellum, which results in impaired executive and psychomotor control performance.

In relation to specific driving skills, alcohol dose has been associated with decreased ability to divide attention, increased complex reaction time (i.e., the time required to respond to two or more stimuli, decreased tracking ability (i.e., ability to maintain position on a roadway), and decreased hazard perception. Younger drivers have, specifically, been at higher risk of cognitive impairment including memory dysfunction, divided attention and visuospatial (visual perception of objects) deficits after consumption of even small to moderate amounts of alcohol than older drivers.3

4 . Psychological trait: Risky driving behaviour has been found to be associated with the individual’s propensity for sensation seeking and their psychological distress as indicated by anxiety and depression. Rewards associated with driving including the experience of pleasurable sensations such as excitement and status among peers, also appear to influence the driving behaviour of the young novice.

The constructs have been operationalised generally as ‘Sensitivity to Reward’ and ‘Sensitivity to Punishment’, they are underpinned by a theory of personality which is essentially neuropsychological and is explained in terms of systems of behavioural activation and inhibition, two of the three systems of ‘Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory’.3

The ‘Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory’ of personality was proposed by British psychologist Jeffrey Gray, and incorporated three neuropsychological systems which are fundamental to the nature of an individual’s personality. Two of these systems relevant to young novice driver risky behaviour because they help regulate the behaviour of the individual: they are the ‘Behavioural Activation System’ and the ‘Behavioural Inhibition System’. They are orthogonal to each other.

The ‘Behavioural Inhibition System’ and the ‘Behavioural Activation System’ regulate behaviour through their operation as feedback systems, with the ‘Behavioural Inhibition System’ sensitive to be punishments and consequently ‘inhibiting’ behaviour in aversive (unpleasant stimuli that induce changes behaviour) circumstances, whilst the ‘Behavioural Activation System’ was thought to be sensitive to rewards, therefore ‘activating’ behaviour in rewarding circumstances, such as during driving.

It can be considered that ‘Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory’, as a neuropsychological theory using the ‘Behavioural Activation System’ and the ‘Behavioural Inhibition System’ (as measured by sensitivity to rewards and punishments respectively) to explain the risky behaviour of young people, is consistent with the evidence for the role of brain maturation in this behaviour.

‘Sensitivity to Reward’ was strongly associated with ‘Personal Propensity to Sensation Seeking’, and each trait was strongly associated with the self-reported risky driving behaviour of the young novice drivers. Anxiety and Psychological Depression’ were strongly associated with ‘Sensitivity to Punishment’ and with self-reported risky driving behaviour. Psychological distress has been found to be a significant predictor of self-reported risky driving behaviour by young novice drivers.

Moreover, factors such as consumption of drugs ( including legal medication that causes drowsiness e.g. cough syrup, anti-histamine table ), excessive vehicular speed, racing, competitive driving against another vehicle in a manner of ‘Show off’, aggressive driving such as driving too close to a vehicle, constant attempts of overtaking, using a hand-held mobile phone, driving when suffering from a medical condition, poorly maintained or dangerously overloaded vehicles for downfall income, driving under-skilled driver or assistant and irresponsible driving of a vehicle in a densely populated or residential area, education institutions, marketplace or in front of commercial establishments.

Lack of punishment of drivers

Along with disregard for public health and safety on the road, lack of administrative accountability and lack of punitive measure for guilty drivers encourage risky plying of motor vehicles. Road Traffic Accidents have an enormous annual economic cost of $518 billion worldwide, representing approximately 1-3% of the gross national product of developed countries such as Canada.

Of the top 10 causes of death, the World Health Organisation’s findings on the global scenario must be taken into consideration. Of the nearly 57 million death from 1,250,000 casualties around the world in 2016 more than half were due to the top 10 causes. Stroke and heart-related disease is the primary killer that killed 15.2 million, keeping its pace with global diarrhoea that took 1.4 million lives in 2016 the death toll from road injuries nears the diarrhoea killing exactly the same number of lives.

Observing the duo figure, it is to be observed that death from road injuries that was placed at tenth in 2000 advances to seventh place in 2016, causing more causality and taking more lives.

Road traffic fatality: global picture

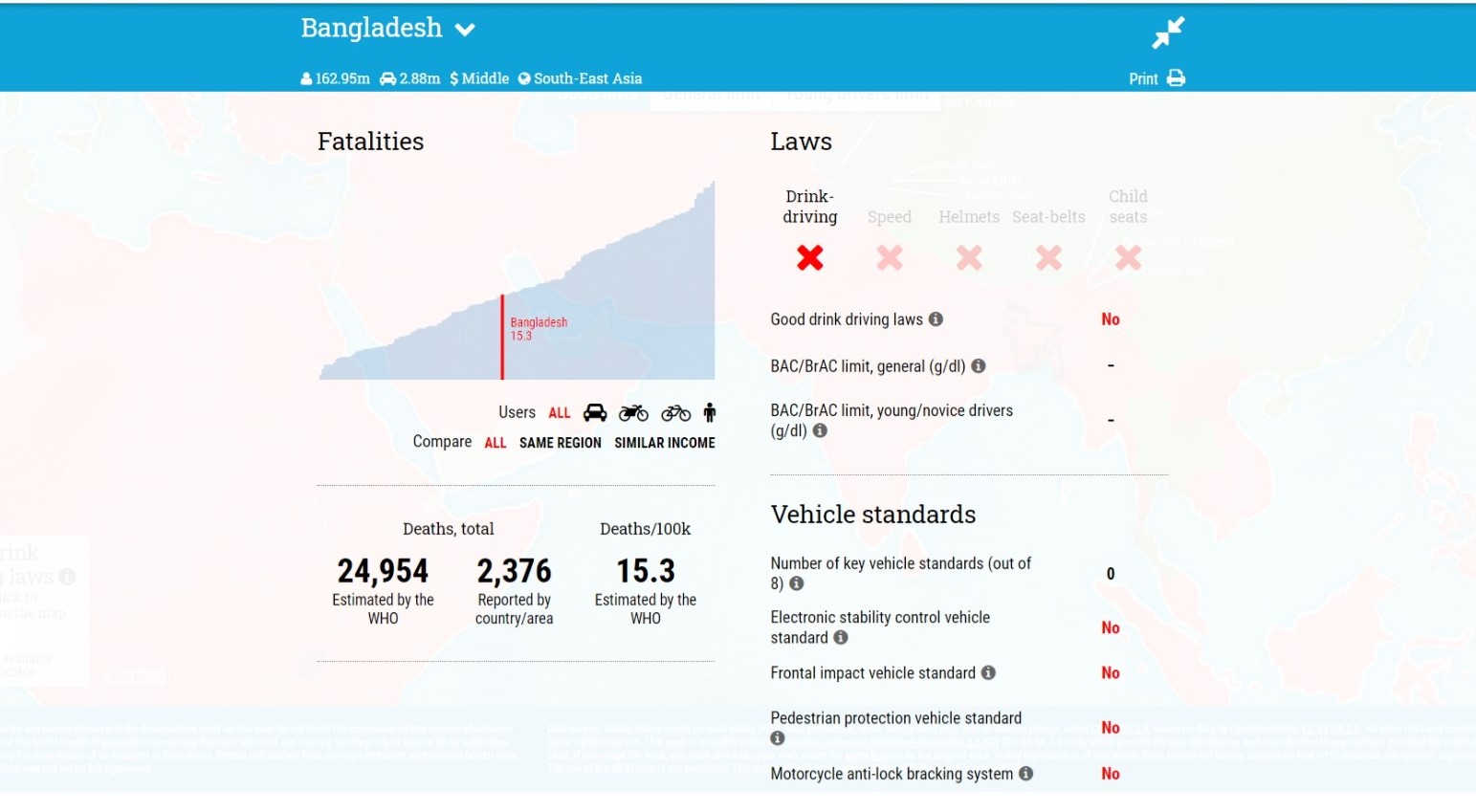

According to worldlifeexpectacy.com’s to fifty common causes of death in Bangladesh Road Traffic Accident is ninth, followed by kidney disease, deadly cause only to take 15.57 lives in 100,000 which 2.62 per cent of all deaths occurred. The World Bank ranked at 103. Claiming 2,394 lives Drug and substance abuse stood at 39 with an average of 0.30 per cent Neighbouring countries India and Pakistan are doing better in either controlling their Motor system or punishing the guilty drivers which keeps their recklessness on road in check as Road Traffic Accident is placed at 11 and 12.

But WHO shows a better picture of Bangladesh among similar income country group. Compare to Pakistan, Nepal, Cambodia, and India in a similar regional grouping. According to WHO the death toll from Road Traffic is 13.6 in 100,000 which means of the total current population of the country the results stand at a staggering 226,043 on average. But WHO estimates 21,316 death in 2015, and a leading English daily, 2017, reported 6823 deaths in just one year. Lack of enforcing the law is of the main reasons for accidents.

An investigative study carried out of the time span of 2016-12107 by The Daily Star shows that death from reckless or dangerously motor vehicle operation significantly increased over the period.

News circulated that, unfit vehicles are the key reasons behind road accidents. 70,000 vehicles did not have a fitness certificate for 10 years in Dhaka. The primary reason behind for unfit vehicles to be able to ply without fitness is the authority’s inability to enforce the law strictly because of political highhandedness in the organisation, corruption in procuring licenses, bribery, cronyism and collusion of bus owners with the law enforcement agencies.

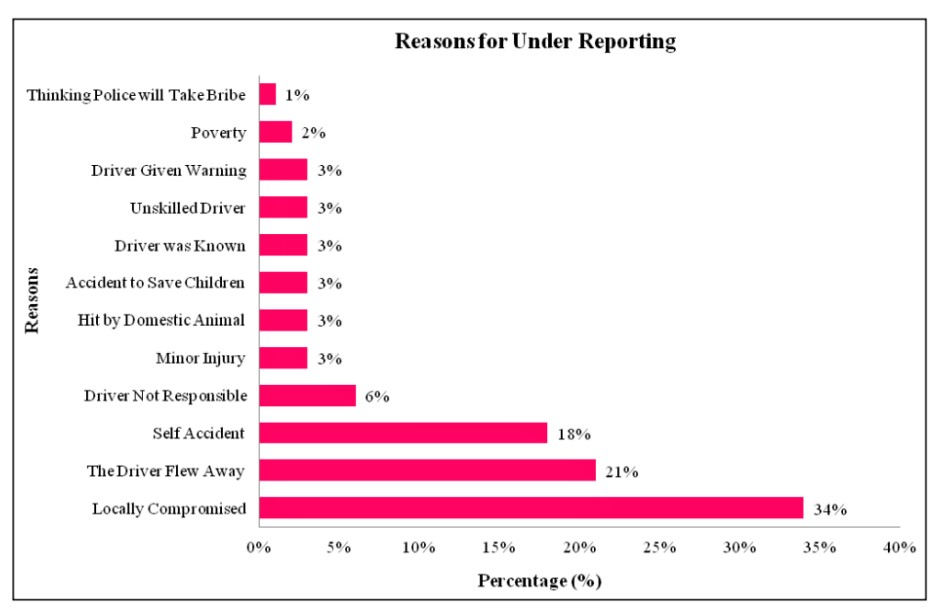

A study conducted in 2013 by two Bangladeshi researchers found that 60 per cent of road casualties are under-reported to the police station. 34 per cent, the highest of all the reasons is a local compromise. they also mention the types of collisions and sorts of accidents on their paper. Having said that ‘hitting pedestrians’ remains the primary type of casualty.

Road Traffic death is responsible for 17.4 deaths in every 100,000 around the world. In UAS drug or substance overdose death rate is 24.58 in 100,000 where the Road traffic-related death is 10.6.

Someone on the road dies every 25 seconds around the world, it could be your mother sister father, as I write this according to the World Health Organisation 1941 people today, 39523 this month and 767239 people died on the road this year already.

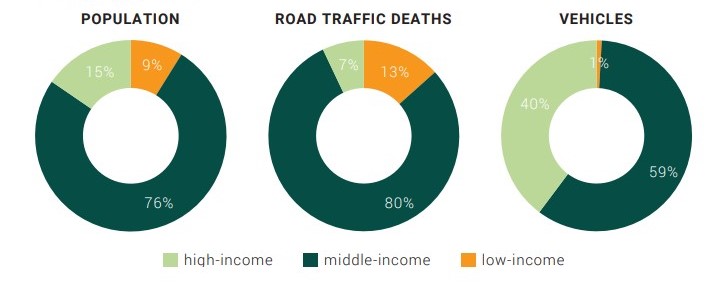

The annual point of this shocking death is 1.2, a number bigger than caused by TB or malaria, of the death more than 137 cyclists, 772 pedestrians, 786 motorcyclists. The lowest death rate is in the Western European region and the highest in the African region with 26.6. In fact, 90% of death occur in low and middle-income countries like Bangladesh. These countries have nearly half of the world’s vehicles.

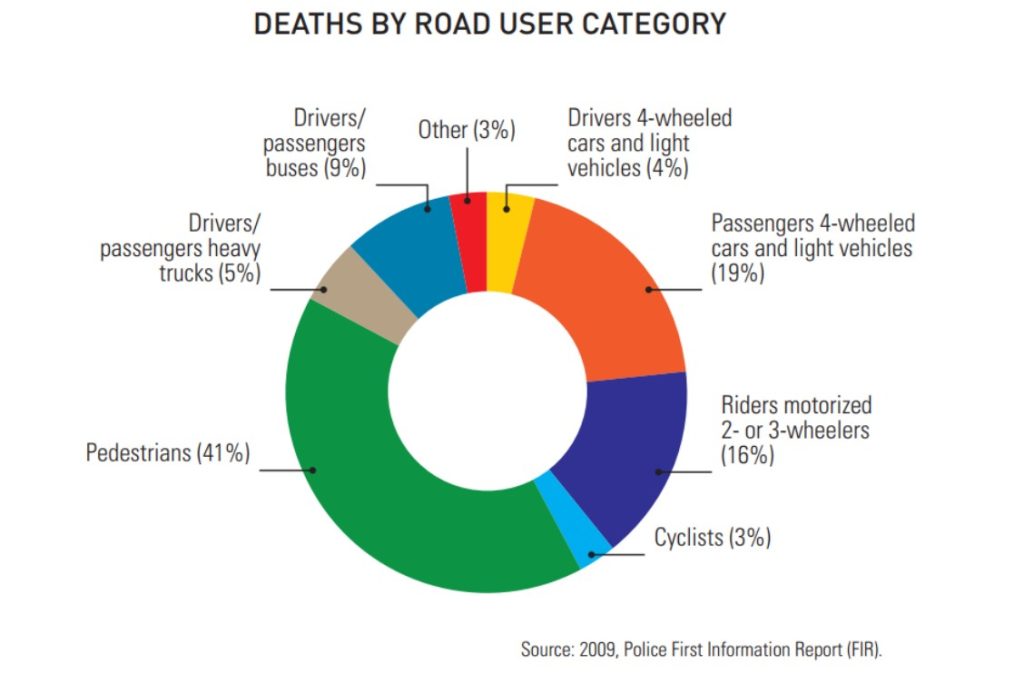

Globally, pedestrians and cyclists represent 26% of all death, with those using motorised two-and three-wheelers comprising another 28%. Car occupants make up 29% of all deaths and the remaining 17% are unidentified road users.

Legal complexities and lack of legal provision for punishing drivers

In Canada, Death or bodily harm in Road Traffic injuries can earn someone a maximum of 10 years of imprisonment. Under the Canadian criminal code, the guilty driver can be punished for life as per the dangerous operation of a motor vehicle.

In Northern Ireland, under Road Traffic Order 1995 A guilty person gets life imprisonment of any term exceeding 5 years, or fine or both. In the UK, as per the Road Traffic Act, 1988 defines, a person who drives mechanically propelled vehicles dangerously on a road public place is guilty of the offence. Prior to the 2015 Motor Vehicle Act 1988 of India passed the bill the third party insurer, depending on the different court pronouncements, compensation money is ranged from 5 lac to 5 crore rupees.

The Cabinet’s approved draft of The Road Safety Act 2017 is mockingly inadequate for the victims of the road traffic accident, in Bangladesh. The draft talks about punishment ranging from one to three months of imprisonment with Tk. 5,000 to 35,000 monetary fine for being intoxicated or using the phone while driving, but it does not include any provision regarding life-threatening or fatal accidents or bodily injury.

But the latest move by the Bangladesh government to hand tougher punishment to guilty drivers is indeed a welcoming and public friendly one. On August 6, 2018, the Bangladesh cabinet approves maximum jail terms to five years for reckless driving death, while it is just a six-months of a jail term or TK. 20,000 fine or both for driving unfit vehicles.

It came up to a hurried draft for stricter punishment to the guilty driver for driving a motor vehicle in an irresponsible manner, as for victim’s family of injury and those killed in a road accident, the government will raise funds from the contribution of the transport owner and offenders. But it did not specify any mandatory and specific monetary compensation for victims or victim’s family.

But will merely passing law after law be able to curtail the current trend of the road accident, fatality, and waywardness of motorists’? Is punishment or tougher provision help the public from dying in the street, on the road? Apart from the government to frame act, what state duty does it have? Or how people’s duty toward the country? Or what can a citizen do to make a safe, liveable and peaceful city?

Punishment alone for the guilty party on the road is not conducive to reducing traffic causalities, accidents to take place, people to die on road, and drives’ rowdy behaviour, in the Bangladeshi context.

On the contrary, it may compel the drivers to go extra length regarding police bribery and street corruption may take to a new height. As discussed above, it may lead drivers to the psychological level to “reinforce” the rewarding activities that they manage to maintain trough unlawful action, as long as there is “the more you earn for me, the more you earn for yourself” conception is entertained by the public transport owners; or “my money can buy the traffic personnel” by rich, or “my political leaders or position help me flout laws” by frequent ‘lawbreakers are lawmakers’.

Regarding punishment to errant drivers the psychological concept of “Operant Conditioning”, a learning process through which the strength of a behaviour is shaped by ‘reinforcement’ or ‘punishment’. Operant Conditioning proposes ‘Reinforcement’ and ‘Punishment’ with ‘positive and ‘negative’ outcomes that increase a particular behaviour among animals. Like ‘Reinforcement’ ‘Punishment’ too, produces ‘positive Punishment’ and ‘Negative Punishment’ result that decreases a particular response.

‘Positive Punishment’ occurs when punishment is responsible for producing a response that decreases its probability in the future in similar circumstances. For example, if any law-breaking citizen is apprehended by the law enforcement personnel and get away with the crime using power, money and fame then he may likely to repeat the action in the future, an action that can be pleasant to him.

Negative Punishment’ takes place when a response from punishment decreases stimuli, it is also known as the ‘Punishment of removal’, for example, if any police personnel found guilty of committing unlawful activity, it not imprisoned but his ‘necessities’ of survival need to be removed.

Punishment alone of the guilty party will not prevent people from dying on the road and accidents taking place as long there is the scope of getting away with killing someone on the road through corrupt means.

Unhealthy completion of making more trips in a view to making extra bucks, the trip-wise salary of the motorists, using political ties by the vehicle owners in the legal procedure, constant propensity to breaking law, the unusual practice of picking of passengers at driver’s will are some common impediments towards enforcing the traffic laws which cannot be removed by mere punishment, especially in a country where many legal issues can be manipulated with money and political mechanism.

The Japan connection: a lesson

That is to say, in order to reduce traffic fatalities or road casualties Japanese model of implementation of the law, and punishment approach is something to consider in Bangladeshi society.

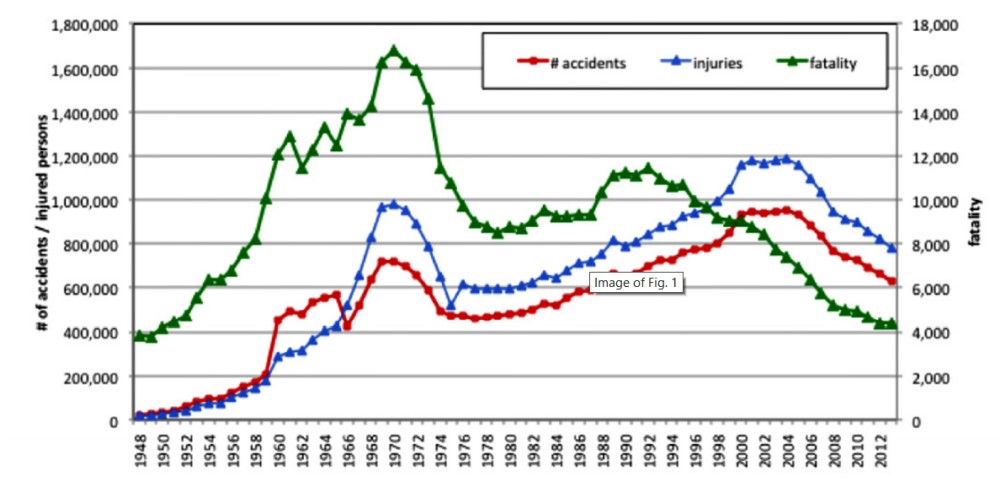

First to be motorised after WWII, Japan witness along with the economic boom, an enormous increase of traffic accident and fatality from 1950 to until the 1980s. There have been four main eras of traffic accident fatality trends: up to 1970, from 1970 to 1981, from 1981 to 1992, and from 1992 to the present. The whole annual estimated social costs and monetary loss, the Cabinet Office of Japanese Government came up in 2004, of road traffic accidents in the early 21st century in Japan was around 8.4 trillion Japanese Yen.

The population grew by 23% from 1951 to 1970, increasing from 87 million to 103.7 million. The Japanese GDP changed from 8.5 trillion yen in 1955 to 75.3 trillion yen in 1970; in the span of only 15 years, the national GDP grew by almost nine times. The country’s rapid economic growth during the first era, evident in the GDP increase and the rapidness that occurred as a result of the enormous changes in vehicle ownership, was the main cause for the increasing fatality trends. In addition, facility development was unable to keep pace with rapid economic growth and motorization.

Note that “fatality” is defined as death within 24 h of an accident, in accordance with the traffic safety statistics gathered by the National Police Agency (NPA) in Japan. This definition applies hereinafter.

In the late 1960s as non-professional drivers’ involvement as offenders and victims became clear the Japanese authority moved on to recruit qualified drivers as well as to take action against underqualified, unqualified and drunk drivers. After installing better tariff signals, placing road marking the Japanese government launched an awareness campaign encouraging compliance with the traffic rules.

“Traffic and safety” researcher Takashi Oguchi says “In 1967, the authorities established a compulsory road training program for obtaining driving licenses and a system of short training courses that drivers would need to undergo every 3 years to renew their licenses.4 The introduction of traffic signal systems and the development of signal control algorithms, along with the establishment of traffic laws and traffic regulations, are also effective measures. Other important components include the education of road users and the proper introduction of traffic law enforcement.

- Knows as the period of “Traffic War In the first era, annual fatalities increased rapidly and reached an annual total of in 1971. The Japanese national government and the Japanese people, as well, considered the Traffic War to be an impending, serious crisis, and the government started to form comprehensive measures to reduce traffic accident fatalities.

- After that (from 1970 to 1981), annual fatalities declined during the 1970s and reached 8719 in 1981. This period constitutes the second era, when annual fatalities trended downward.

- Despite (1981 to 1992) substantial efforts to reduce traffic safety risks, annual fatalities increased again in the third era and eventually reached 11,452.

- In the fourth and final era, which began in 1992, the annual number of traffic accidents has shown increases while annual fatalities have dropped. In the first era (−1970), the increasing fatality trends are obvious. The annual fatality figures changed from 4429 in 1951 to 16,765 in 1970; in other words, the figure for 1970 was almost four times larger than in the figure for 20 years earlier. Vehicle ownership, meanwhile, rose from 413 (thousand vehicles) in 1951 to 16,528 (thousand vehicles) in 1970—a fortyfold increase over the span of just two decades.

That number of pedestrian bridges across the country jumped to about 5000 in 1970 and approximately 9000 in 1980. The steady upward trend continued up to around 2000. When pedestrian bridge construction first started, the new facilities had a sizable impact on protecting pedestrians from traffic accidents: comparing the number of accidents in the six-month periods prior to and after bridge installation, there was an 85% decrease in the numbers of pedestrian-involved in traffic accidents.

One can, however, divide the wider ageing policies for traffic safety measures into the five categories below:

1 . Traffic safety facilities and road traffic environment: The number of traffic signals in Japan rose rapidly from about 15,000 in 1970 to about 95,000 in 1980 (and now to almost 205000 in 2013 which were significantly effective in reducing the number of road accidents. Policymakers started actions such as– selecting high-risk traffic accident locations, conducting scientific analyses to identify factors behind traffic accidents, determining and implementing measures to reduce risks of incidence, and evaluating implemented measures – in accordance with the well-known PDCA (Plan, Do, Check, and Action) cycle.

2 . Regulations and law enforcement: As the process of motorization has progressed, lawmakers have developed both traffic laws and various types of traffic regulations. The Road Transport Vehicle Act was established in 1951 to ensure the safety of surface transport vehicles and define several vehicle safety standards in Japan. The revised Act later required all passenger vehicles manufactured after 1975 to be equipped with seat belts.

The Road Traffic Law of 1971, meanwhile, required drivers and passengers in cars travelling on expressways to use seat belts but did not stipulate any specific penalties. The 1985 revisions to the law obligated people sitting in the front seats of cars to wear seat belts on expressways, a requirement that came along with penalty points for violations.

The same regulation was applied to other types of roads in 1986 and extended to passengers sitting in the back seats of cars in 2007. The Japan Automotive Federation (JAF), the union of automobile users in Japan, reported the overall average seat belt usage rates are 98%, 93%, and 35% among drivers, passengers in the front seat, and passengers in the rear seat, respectively. The effectiveness of wearing seat belts was seen as a means of reducing accident injuries and fatalities. The key problem is how to raise the percentage of drivers and passengers who wear seat belts.

3 . Education and publicity: The research also covers the driving license system and the points system defined in the “Road Traffic Law”. Since 1967, the age requirements for the various types of driving licenses have been 16 years or older for motorcycles, 18 years or older for regular vehicles, 20 years or older for large-sized vehicles, and 21 years or older for transport business-purpose vehicles.

The point system was introduced in 1969. If a driver causes an accident or commits a traffic offense, the driver accrues a certain number of points; when the driver’s total number of points reaches a certain level, the authorities may suspend or revoke his or her license (Punishment of removal necessity). Accruing points is not in and of itself a criminal punishment—punishment and legal action only enter the picture when a driver’s total point count exceeds a certain level.

In order to respond to popular demand and prevent severe traffic accidents more effectively, policymakers have revised the penalty points, altered the fine amounts, and introduced new offenses subject to penalty points.

Obtaining a driving license in Japan is a difficult, time-intensive, and high-cost process of acquiring the necessary knowledge and skills. As of 2015, people in driving instruction programmes at certified driving school need to complete 34 h of practical training and 26 h of lectures on laws and vehicle mechanics to obtain a normal regular vehicle license under the Operational Rules for Road Traffic Law. The Road Traffic Law specifies the certification and standards of these schools, and the curriculum established by the Traffic Bureau of the NPA defines the content of the training courses on a nationally standardized basis.

Follow-up driver education is also conducted at the time of issuance of the initial license, and subsequent classes are conducted every 3 years at the time of license renewal. The license renewal period for dedicated excellent drivers (people who have accrued no penalty points over the past 5 years) was extended to 5 years via the 1994 revisions to the Road Traffic Law. Drivers who have caused accidents or committed violations during the period leading up to license renewal are required to take special lecture courses.

4 . Improvement of vehicle safety standards: The safety standards for the structure and performance of automobiles in Japan conform to the Road Transport Vehicle Act, which was established in 1951 and revised many times—sometimes to make the standards more rigorous, and sometimes to relax the regulations. Before the 1970s, the dominant type of traffic accidents was known as “mobile weapon” accidents: vehicles causing pedestrian injury or death. In the early 1970s, however, there was an increase in so-called “mobile coffin” type accidents—incidents that kill the drivers or passengers of automobiles.

As public scrutiny grew, lawmakers strengthened the vehicle safety standards in 1973 and established three basic concepts for consolidating vehicle safety measures for consolidating vehicle safety standards like the requirements for tachographs, speedometers, triple-brake systems, and so forth for large trucks, as well as seat belts, headrests, and other items for passenger cars, that were designed to reduce damage to passengers in the event of a collision. Interestingly, in Bangladesh, Report says there are 2 million vehicles is still unregistered, 3.5 million are registered and only 1.23 million professionals were licensed. Additionally, only 600,000 plus vehicle gets an annual fitness test out of 1 million-plus vehicles.

Road traffic casualty situation in Bangladesh. Source: World Health Organisation

5 . Emergency medical care: Although maintaining a system of emergency medical care is not an accident prevention measure in itself, having a solid emergency medical care system in place obviously reduces the human damage that traffic accidents can cause. The number of emergency hospitals in Japan grew from 2843 in 1972 to 3471 in 1983. In 1965, ambulances only carried around 100,000 people despite the relatively high numbers of accidents (567,000) and traffic accident fatalities (approximately 12,500).

The fatality rate, or the number of deaths per number of accidents, was around 0.022 in 1965—a much higher figure than the rate of 0.007 (= 4373 fatalities/629,021 accidents) in 2013 when the number of people being carried in the ambulance was around 530,000. The increase in the number of people carried by ambulances may be an important contributor to the decreased fatality rate. The rapid advances in medical technology in recent years likely also play a role in saving lives in situations where traffic accidents inflict severe damage on people. These achievements have surely helped reduce the number of traffic accident fatalities, especially in recent years.

Though health investment has increased as high as 2.8 of the country’s GDP, the health sector is one of the most critical sectors in Bangladesh where out-of-the-pocket (OOP) medical post is still 64% of the total health expenditure.

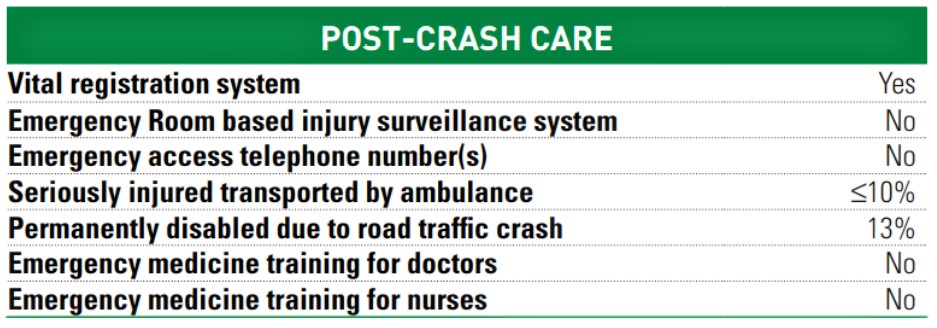

According to WHO in order to minimise the fatality and bodily harm there is hardly any emergency medical service available for post-crash patients. Avail ambulance in crash sites, emergency medical service and a medical service centre within the close vicinity: are the objective we need a serious discussion about.

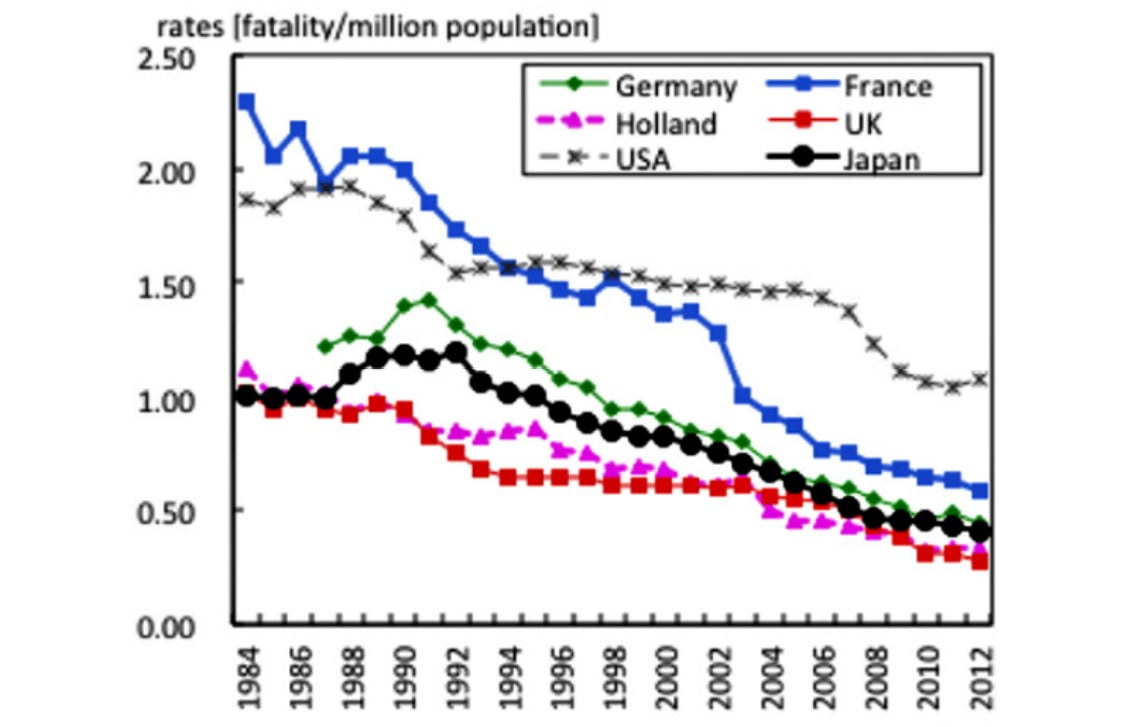

Today as we compare japan with other countries where road traffic casualties and fatality always renamed to the lowest, it pares better than France, Germany and the USA. The UK and the Netherlands have always been better. Looking at the most recent statistics (for 2012), one can see that the fatality rate in Japan (0.41 fatalities per million people, Bangladesh 13.6) is almost the same as that in Germany (0.44); on the other hand, the fatality rates in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom are at 0.34 and 0.28, respectively.

But, instead of expecting the state or the government to do all the possible urban works in a view to make civic living comfortable, easy and uninterrupted from the external threats to one’s existence, we, as aware and law-abiding citizens of the state have expected civic or civil duty to perform. We can’t just expect to the government to be an insurer of safety and comfort from cradle to grave. In acquiring a more liveable and peaceful country the equal responsivity- as equal as government- lies with a civilian. The more civic involvement with voluntary responsibility is involved in the state the less we feel insecure, and governed.

Conclusion

Sweden is a global leader in road safety performance with 2.8 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. Between 1990 and 2015 the number of road traffic deaths decreased by 66%. Experience in Sweden illustrates how better results can be achieved through long-term, perennial planning of systematic, evidence-based approaches to intervention, supported by a strong institutional delivery including leadership, sustained investment and a focus on achieving ambitious road safety goals and targets across government, business and civil society.

Achieving global and national road safety goals and targets requires appropriate management capacity. Such capacity should be demonstrated through effective institutional leadership within responsible agencies, multi-sectorial coordination arrangements, sustainable funding and data systems to measure, target and monitor progress.

The 9, 10 and 11 targets of the ‘Sustainable Development Goals for Road Safety’ by 2013 is halving the numbers of traffic injuries and fatalities related to drivers using alcohol, reduction to other psychoactive substances; making all countries restrict or prohibit the use of mobile phones while driving; having all countries get enacted the regulation for driving time and rest periods for professional drivers must be ensured first.

Bogota in Colombia was able to reduce the number of traffic deaths by 50% between 1996 and 2006, by implementing an integrated approach to road safety and urban mobility. The Republic of Korea has experienced the 3rd largest decline in traffic fatality rates among OECD countries since 1972.

Enacting and enforcing legislation in Bangladesh on key risk factors are critical components of an integrated strategy to prevent road traffic deaths and injuries. Implementing laws without any preferential consideration, building traffic and pedestrian-friendly star rated roads with, “Sidewalk present, signalized crossing with refuge, street lighting, off-road dedicated cycle facility, raised platform crossing of major roads, dedicated, separated motorcycle lane, central hatching, no roadside hazards, straight alignment, safety barrier separating oncoming vehicles and protecting roadside hazards would be a must to halt traffic road casualties”.

Punishment alone would not bring expected results if laws are enforced with proper education, training, incentive, public awareness about maintaining traffic rules are the potential steps towards even more ‘Safe Road’.

Without civil involvement in civil affairs like keeping our living healthy, maintaining traffic disciplines, proper use of existing state establishment, teaching our children the right things to do, keeping the government in check of its abuse of state power, seeking justice for the polarised sect of the citizens, staying with weak, discouraging activity that threatens individual peace, asking help for the ill neighbour, protesting state-led unrestrained politicisation of state organs, staying on the right side of law and order, behaving in a civil manner, considering the rights and interest of other citizens, adhering to moral principle and paying taxes in a timely fashion is to name a few, would the expected activism toward the state.

Nevertheless, the Road Transport Authority of Bangladesh has come up with a sever Road-traffic act recently. Along with the Japanese system of awarding points to the license holders, the authority is ready to impose fines for driving without licences up to TK25,000 from previously TK 5,000 while TK 1,00000 to up to 5,00000 will the fines for carrying face licence. And death penalty for road accidents as per Penal Code 1860. Having said that, the Road traffic safety movement was a timely one, although the expectation and reality should be realised simultaneously.

Works Cited:

- The acute effects of low dose of alcohol on simulated driving performance in male and female young drivers with high versus low testosterone levels. Eldeb, Manal. Montreal: McGill University, Montreal, 2016. ↩ ↩

- WHO. human tolerance factors. violence injury prevention road traffic activities road safety training_manual unit_2. ↩ ↩

- The influence of sensitivity to reward and punishment, propensity for sensation seeking, depression and anxiety on the risk behaviour of novice drivers: A path model. Scott-Parker, B., Watson, B., King, M. J., Hyde, M. K. Brisbane: British Journal of Psychology, 2012). ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

- Achieving safe road traffic — experience in Japan. Oguchi, Takashi. Tokyo: Advanced Mobility Research Center and Department of Human and Social Systems, Institute of Industrial Sciences, University of Tokyo, 2016. ↩