Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind offers an audacious and sweeping examination of this journey, challenging conventional perspectives with insights that span millions of years yet resonate profoundly with contemporary issues.

Humanity’s journey is a narrative of paradoxes: our species, Homo sapiens, once a marginal group among Earth’s diverse life forms, now stands at the pinnacle of influence, shaping ecosystems, rewriting evolution, and even contemplating its own transcendence.

Background

Harari’s work is remarkable not only for its scope—tracing humanity’s arc from insignificant African apes to planetary dominators—but also for its philosophical depth. The book illuminates 3 pivotal junctures such as the Cognitive Revolution, which endowed our ancestors with the capacity for complex language and shared myths, the Agricultural Revolution, often dubbed “history’s biggest fraud” due to its unintended consequences, and the Scientific Revolution, which catapulted humanity into unprecedented realms of discovery and existential quandary.

Three important revolutions shaped the course of history: the Cognitive Revolution kick started history about 70,000 years ago. The Agricultural Revolution sped it up about 12,000 years ago. The Scientific Revolution, which got under way only 500 years ago, may well end history and start something completely different. This book tells the story of how these three revolutions have affected humans and their fellow organisms.

The purpose of this review is to bridge Harari’s historical insights with our current societal and technological challenges. As Harari aptly observes, “The only thing we can try to do is to influence the direction scientists and engineers are taking science and technology in”. This exploration invites us to interrogate the ethical, cultural, and ecological implications of humanity’s meteoric rise and its fraught future.

What distinguishes Harari’s narrative is his interrogation of what it means to be human. For instance, he poignantly describes early Sapiens as “insignificant animals with no more impact on their environment than gorillas, fireflies or jellyfish,” underscoring the fragility of our beginnings (Sapiens, Chapter 1). Yet, by harnessing the unique ability to weave shared myths—fictions that bind communities and coordinate efforts on vast scales—we transcended biological limitations and ascended the food chain at breakneck speed.

This capacity for collective imagination, as Harari terms it, forms the cornerstone of our species’ success and the source of our most pressing dilemmas.

In reflecting upon the significance of Sapiens, one cannot help but marvel at its ability to intertwine the past with the present. It confronts us with the weight of history and compels us to ask: How did we become who we are, and where might we be headed? As Harari warns, the advent of intelligent design and biotechnology challenges us to reconsider the boundaries of what it means to be human: “Homo sapiens as we know it will disappear within a century or two” (Chapter 20). These insights are not merely academic but deeply personal, as they implicate each of us in the unfolding story of our species.

This review will delve into these themes, connecting the lessons of our evolutionary history with the ethical challenges posed by AI, genetic engineering, and climate change.

Drawing from Harari’s observations and using key passages from Sapiens, we aim to reflect on the human condition—its triumphs, tragedies, and the existential questions that remain unanswered.

1. The Cognitive Revolution

The Cognitive Revolution, occurring between 70,000 and 30,000 years ago, marked a defining shift in human history. It was not merely an enhancement of cognitive faculties but a profound transformation that distinguished Homo sapiens from all other species. This revolution was underpinned by the development of complex language, which enabled humans to gossip, share ideas, and construct myths.

Harari calls this shift the “Tree of Knowledge” mutation, an evolutionary accident that granted Sapiens the unparalleled ability to imagine and collaborate in vast numbers.

The significance of this revolution cannot be overstated. It laid the foundation for large-scale cooperation, the creation of religious and political ideologies, and the eventual dominance of Homo sapiens over the planet. This paper explores how language and imagination fueled human progress, leading to the collective power that enabled civilizations to rise.

Yuval Noah Harari’s exploration of the Cognitive Revolution is a deeply profound narrative about Homo sapiens’ leap from insignificance to unparalleled dominance on Earth.

Approximately 70,000 years ago, a genetic mutation ushered in a new way of thinking, speaking, and imagining that fundamentally altered the trajectory of our species. This moment, Harari suggests, was not merely about survival but about shaping reality itself—a hallmark of humanity that continues to echo into the modern era of AI and digital interaction.

Human Adaptability

Homo sapiens distinguished themselves through an exceptional capacity for adaptability. Harari asserts that before this revolution, “there was nothing special about humans,” who were just another mammal navigating the food chain.

But the Cognitive Revolution enabled humans to rapidly adapt to diverse ecological niches, ultimately spreading across continents in a fraction of the time it took other species. Adaptability, fueled by creativity and innovation, became the cornerstone of survival.

This ability resonates today as humanity grapples with complex challenges like climate change and technological disruptions. For instance, just as Homo sapiens or wise man adapted their environments with tools and fire, contemporary society adapts by innovating renewable energy and artificial intelligence to address crises.

The most transformative element of the Cognitive Revolution was the emergence of fictive language. Harari identifies it as “the most unique feature of Sapiens language”.

Unlike other species that communicate immediate realities—such as the green monkey’s distinct calls warning of lions or eagles—Sapiens developed the ability to imagine, share, and believe in collective myths. This allowed strangers to cooperate on an unprecedented scale, whether through religion, nations, or shared economic systems.

The creation of these shared myths remains pivotal today. In the digital age, storytelling drives global collaboration, from narratives about climate action to brand identities in marketing campaigns. For instance, digital platforms like Twitter or YouTube amplify shared myths, enabling movements like #BlackLivesMatter to mobilize millions. Harari’s insight into myths illuminates why such narratives are integral to societal cohesion and transformation.

The Tree of Knowledge Mutation

Harari refers to the Cognitive Revolution as the result of the “Tree of Knowledge” mutation, a hypothetical genetic alteration that rewired the human brain, allowing for new forms of thought and communication. This mutation was, by all accounts, an evolutionary accident. It enabled Sapiens to create and believe in myths—shared stories that bound large groups together.

“Large numbers of strangers can cooperate successfully by believing in common myths”. Myths allowed for the establishment of social norms and cooperation beyond kinship ties. Unlike other species that rely on instinct or direct experience, Sapiens could align their actions with shared imagined realities.

This ability is evident in the foundations of religions, political ideologies, and even financial systems.

The ability to construct fictions meant that human societies were no longer bound by biological constraints. Harari contrasts this with chimpanzee societies: “Significant differences begin to appear only when we cross the threshold of 150 individuals, and when we reach 1,000–2,000 individuals, the differences are astounding”. Without shared myths, large human settlements would collapse under the weight of social complexity.

The Power of Communication

Harari elegantly describes the evolutionary leap of Sapiens’ language as the ability to “transmit information about things that do not exist” (p. 25). This seemingly simple feature gave rise to storytelling, cultural traditions, and civilizations. Beyond mere utility, language became a bridge to shared purpose, empowering Sapiens to not just survive but thrive.

In our contemporary context, communication technology reflects this evolutionary triumph. The rise of AI, like OpenAI’s GPT models, represents a continuation of humanity’s linguistic legacy. These tools, trained on the vast corpus of human expression, are modern extensions of that ancient ability to store, process, and share knowledge.

Harari’s assertion that Sapiens language is “amazingly supple” finds its parallel in how AI facilitates everything from translating languages to composing symphonies—proving the enduring relevance of cognitive innovation.

The Cognitive Revolution (as explored in Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens) marks a crucial turning point in the history of Homo sapiens, a period around 70,000 years ago when humans evolved new cognitive abilities.

This moment redefined how early humans perceived and interacted with the world, leading to significant shifts in thinking, communication, and cooperation. These changes were not merely incremental; they were revolutionary and foundational to the development of human culture, society, and history.

Language and Imagination and the Rise of Fiction

Harari argues that what made the Sapiens language unique was not just its ability to convey factual information but its unparalleled capacity for fiction: “The most common answer is that our language is amazingly supple. We can connect a limited number of sounds and signs to produce an infinite number of sentences, each with a distinct meaning”. This ability to create and share imagined realities enabled humans to cooperate in ways no other species could.

Other animals communicate, but their communication remains limited to immediate concerns—warnings about predators or signals for food sources. Green monkeys, for example, have distinct calls for “Careful! An eagle!” and “Careful! A lion!”

However, a Sapiens individual could communicate not just about immediate threats but could tell elaborate stories about dangers and opportunities far beyond their current location.

Language also allowed Sapiens to gossip, an essential tool for social cohesion. Harari notes that “Gossip helped Homo sapiens to form larger and more stable bands,” enabling groups to expand beyond the natural limit of 150 individuals—an upper threshold of social bonds maintained purely through direct personal relationships.

Beyond gossip, the ability to discuss abstract concepts and non-existent entities allowed for the formation of complex social structures, such as religions, legal systems, and economies.

Harari emphasizes that while many species, including other primates, use some form of language, human language is distinct in its flexibility and ability to convey abstract and fictional concepts.

This new form of communication enabled early humans not only to share information about their immediate surroundings (such as the location of food or the presence of predators) but also to engage in “gossip”—an exchange of social information about who could be trusted, who was allied with whom, and who was deceitful. This social exchange, though seemingly trivial, was essential in forming larger groups capable of cooperation.

Harari’s suggestion that human language evolved not primarily for the transmission of survival-related knowledge but for social interaction underscores the human species’ need for deep social bonds. “Gossip” was the glue that held early human societies together, allowing humans to form complex networks of trust and cooperation.

More significantly, this linguistic revolution allowed Homo sapiens to create myths and engage in collective imagining. Harari refers to this as a profound cognitive leap that set Sapiens apart from other species.

Unlike chimpanzees or elephants, which could only convey practical, observable realities, Sapiens could create entire worlds in their minds. They could invent gods, laws, and nations that did not exist in the physical world but existed in collective belief.

The invention of myths, religions, and ideologies was not just an intellectual exercise; it was a survival mechanism. Through these shared beliefs, humans could organize themselves in larger groups than any other species on the planet.

Collective Power

Harari explains that before the Cognitive Revolution, Sapiens lived in small, tight-knit groups, much like other primates.

However, after the Cognitive Revolution, humans could collaborate in ways that other animals could not: “Churches are rooted in common religious myths… States are rooted in common national myths”. The ability to believe in concepts such as gods, nations, and laws enabled large-scale social structures to emerge.

This collective power enabled Sapiens to construct vast networks of cooperation. Unlike wolves or chimpanzees, which can only form stable social units of a few dozen members, Sapiens formed tribes, kingdoms, and empires spanning millions.

Harari states: “Homo sapiens conquered the world thanks above all to its unique language”. The myth of national identity, for example, allows people who have never met to fight and die for their country, just as religious myths inspire believers to engage in rituals and wars.

The birth of complex institutions, such as trade networks and legal systems, was possible because humans could share common beliefs. “A modern corporation exists only in our collective imagination”. Without shared beliefs, money would be worthless, and laws would have no authority. These imagined realities, while intangible, wield immense power over human behavior.

However, myths like religions, national identities, and political ideologies empowered humans to unite around abstract concepts and cooperate with people they had never met before.

This collective power enabled Homo sapiens to organize vast societies, build empires, and establish religions. Harari uses the example of the Stadel lion-man—a 32,000-year-old figurine found in Germany—as one of the earliest pieces of evidence of human imagination at work.

The figurine is not just an artistic object but a representation of the human ability to merge the real and the imagined.

This ability to construct shared fictions had profound consequences for human cooperation.

Harari argues that the Cognitive Revolution allowed Sapiens to leap to the top of the food chain, not through brute strength or superior technology, but through the creation of social structures built on common myths.

In Harari’s view, this capacity for collective imagination and cooperation is what made Homo sapiens the most successful species in history.

Myths like religions, corporations, and nations are social constructs, but their power lies in the fact that large groups of people believe in them. These collective beliefs allow Sapiens to build cities, wage wars, and create civilizations that would be impossible without shared understanding and cooperation on a mass scale.

The Cognitive Revolution Timeline

–100,000 years ago: Early Homo sapiens in Africa exhibit no significant behavioral advantages over other hominins.

-70,000 years ago: The Cognitive Revolution begins, marked by the emergence of complex language and symbolic thought.

– 45,000 years ago: Sapiens expand beyond Africa, replacing Neanderthals and other human species.

-30,000 years ago: The first known art, religious symbols, and evidence of large-scale cooperation appear.

-12,000 years ago: The Agricultural Revolution builds upon the Cognitive Revolution, leading to permanent settlements and the rise of civilizations.

The Cognitive Revolution remains one of the most crucial turning points in human history. The development of complex language enabled humans to gossip, imagine, and collaborate on an unprecedented scale.

Without this revolution, the vast empires, religions, and ideologies that shape our world would not exist. The ability to believe in abstract concepts turned Sapiens into the dominant species, surpassing all other human and animal groups.

Harari’s work compels us to recognize the power of stories and myths—not just as remnants of the past, but as the very fabric of our societies today. Indeed, the most powerful forces shaping our world are not physical realities, but the shared fictions that humans have imagined into existence.

2. The Agricultural Revolution

The Agricultural Revolution, which occurred around 12,000 years ago, marked the transition from a nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle to one based on agriculture. This pivotal transformation involved the domestication of plants and animals, enabling humans to settle in permanent communities, thus reshaping society and human interaction with nature.

History’s Biggest Fraud

In his profound critique, Harari provocatively claims that the Agricultural Revolution was history’s greatest deception. Contrary to the traditional belief that it was a step toward progress and abundance, Harari argues that the shift from foraging to farming was a trap rather than a triumph.

Far from leading to a more comfortable life, agriculture imposed a heavier workload on humans. While foragers worked fewer hours and had a diverse diet, early farmers toiled long hours cultivating crops like wheat, which, paradoxically, led to poorer nutrition and more disease. Harari draws this from Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel.

The development of agriculture, Harari explains, was not a result of conscious, strategic planning by early humans but rather a series of small steps, decisions, and unintended consequences. For example, wheat—a humble grass species that once grew only in specific areas—became the dominant food crop and expanded across the globe, covering millions of square kilometers.

However, it was wheat that domesticated humans, compelling them to labor under the harsh sun, shifting their way of life dramatically. This manipulation of Homo sapiens by crops like wheat is the essence of Harari’s argument that humans fell into a “luxury trap”.

Agriculture led to overpopulation, which in turn generated more work, as more hands were needed to sustain larger communities. As a result, instead of improving the quality of life, agriculture led to a decline in human well-being. With this “luxury trap” came the illusion of progress.

Human societies believed they were improving their circumstances by producing more food, but in reality, they were becoming more dependent on a narrow range of food sources, making them vulnerable to crop failures and famine.

Impact on Society

The Agricultural Revolution also had far-reaching consequences for social structure, economy, and human relationships.

The move from nomadic to sedentary life necessitated the creation of permanent settlements, which, in turn, led to the emergence of hierarchies and class systems. With agriculture, some individuals could accumulate surplus food, leading to the establishment of elites who controlled the food supply. This concentration of resources and power led to the formation of social inequality, as the masses worked harder to sustain the ruling class while reaping fewer rewards.

Farming communities, unlike nomadic bands, were rooted in one place, and this rootedness created a new economic order. It brought about specialization, with individuals engaging in different trades to support the growing settlements. The result was a highly structured society that relied on agriculture not just for food but for the very organization of life.

The environmental impact of agriculture cannot be overstated. As humans learned to domesticate plants and animals, they began to reshape the landscape, clearing forests for farmland and altering ecosystems. This manipulation of the natural world had both immediate and long-term consequences, including the extinction of numerous species, changes in climate patterns, and the depletion of biodiversity.

Beyond the physical toll, the shift to farming also changed human psychological and social dynamics. Harari points out that early farmers were far more prone to violence than their forager predecessors. Disputes over land, resources, and food became commonplace in agricultural societies, where wealth accumulation and property ownership increased tensions between neighboring groups.

The Paradox of Success

The success of the Agricultural Revolution can be viewed through two lenses: the evolutionary and the existential. From an evolutionary standpoint, it was undeniably successful. Agriculture allowed Homo sapiens to thrive in unprecedented numbers, expanding their influence across the planet.

The number of humans multiplied exponentially, ensuring the survival and dominance of the species

However, this evolutionary success came at a great cost to individual well-being. Early farmers lived shorter, more disease-ridden lives than their foraging ancestors. Their diet, reliant on a limited range of staple crops like wheat and rice, lacked the diversity of the hunter-gatherer diet, leading to malnutrition and dental problems.

Moreover, as farmers became more settled and dependent on their crops, they became more vulnerable to environmental fluctuations and crop failures, making famine a constant threat.

This paradox—that the Agricultural Revolution, which allowed humanity to flourish, also led to widespread suffering—underscores the complexity of human progress. Harari argues that while Homo sapiens may have triumphed on a species level, the cost to individual happiness and well-being was immense.

The lives of individual farmers were marked by hardship, backbreaking labor, and increased vulnerability to disease and violence.

The Agricultural Revolution was a transformative period in human history, one that reshaped the way we live, work, and relate to the environment. However, as Harari provocatively suggests, it may not have been the unmitigated success that many imagine it to be.

The shift to agriculture led to more work, social inequality, environmental degradation, and greater human suffering. In many ways, the Agricultural Revolution was a double-edged sword: it allowed humanity to prosper as a species while imposing new hardships on individual lives.

In reflecting on this history, we are reminded of the delicate balance between progress and well-being. While the Agricultural Revolution laid the foundations for modern civilization, it also serves as a cautionary tale of how advancements that appear to promise abundance and security can instead lead to new forms of dependence, inequality, and suffering. The lessons of this era continue to resonate today, as we grapple with the consequences of our own technological revolutions and the impact they have on our health, happiness, and the environment.

The Unification of Humankind

Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens presents a sweeping examination of humankind’s gradual journey towards unification, tracing the complex web of empires, religions, and economic systems that helped bind the human species into a single global community.

It is both a historical inquiry and a meditation on the philosophical underpinnings of our societies.

From a deeply personal perspective, I find Harari’s exploration particularly compelling in how it challenges the traditional narrative of human independence. We are not solitary entities, but participants in an intricate tapestry woven from ideologies, beliefs, and shared structures that transcend time and place.

Money and Trade: The Great Unifier

Harari’s analysis of money as a tool for unification reveals its paradoxical role: a force both transactional and transcendental. His observations highlight the fact that while money may be seen as a root of societal evils, it is, in fact, “money is also the apogee of human tolerance. Money is more open-minded than language, state laws, cultural codes, religious beliefs and social habits. Money is the only trust system created by humans that can bridge almost any cultural gap, and that does not discriminate on the basis of religion, gender, race, age or sexual orientation. Thanks to money, even people who don’t know each other and don’t trust each other can nevertheless cooperate effectively.”

Money allows us to cooperate with complete strangers, transcending boundaries of religion, ethnicity, or social status. While religion asks us to believe in metaphysical truths, money simply requires us to believe that others believe in its value—a universal trust that binds people across time and geography.

This concept of trust-based cooperation, reliant on shared belief rather than personal relationships, reflects humanity’s evolving social structures.

In many ways, Harari argues, money “frees us from the tyranny of personal relations” by enabling fluid, large-scale cooperation without the burdens of familiarity. This is perhaps one of the most profound insights of Harari’s work—how a concept as abstract as money can bridge the chasms between cultures, enabling empires to rise and trade networks to flourish.

In the realm of trade, money serves as the quintessential equalizer, leveling economic playing fields between otherwise disparate regions.

Consider how, in ancient trade routes between India and the Mediterranean, the demand for gold skyrocketed once merchants realized its varying value in different places. This process—economic homogenization through trade—mirrors the unification of humankind.

The circulation of goods, ideas, and currencies laid the groundwork for a more connected global society, and in doing so, erased the artificial distinctions that might have kept civilizations apart.

Tools of Unification

The role of empires and religion in Harari’s account of human unification is equally fascinating. Empires, by their very nature, impose a uniform system of governance and law over vast territories.

As Harari notes, these systems allow diverse populations to cooperate under a common framework, enforced by military strength but sustained through shared cultural ideals. The Roman Empire, for instance, was not merely a political entity but a civilization that standardized language, law, and commerce across Europe and parts of Africa and Asia.

Religion, too, has been a unifier of peoples, though in a more ideological sense. Harari describes how religion provided the superhuman legitimacy needed to stabilize fragile social structures. Islam, Christianity, and other faiths unified large populations by offering a shared belief system that transcended local cultural practices.

At the height of its expansion, Islam, for example, connected people from the deserts of Arabia to the vast stretches of the African continent under a common spiritual framework.

What is particularly striking is Harari’s claim that empires and religions often succeeded where economic systems alone could not. While money could facilitate trade between strangers, it lacked the power to command their moral allegiance.

Empires and religions stepped into this void, offering both order and purpose, thereby cementing their roles as vital forces in human unification.

Globalization: The World Today

Harari’s examination of globalization is perhaps the most relevant to the contemporary reader, as it traces the historical precedents for today’s interconnected world. The modern era of globalization, he argues, did not emerge from nowhere—it is the logical culmination of centuries of imperial expansion, religious proselytization, and the spread of economic systems.

The global trade networks that emerged in the past laid the foundation for the seamless flow of goods, information, and people across continents.

Yet, Harari does not romanticize this process. He acknowledges that globalization has its dark side: the commodification of human life, the erasure of local cultures, and the potential for economic exploitation. The “universal convertibility” of money has led to a situation where “everything is for sale,” and traditional values have often been trampled in the rush towards profit.

This raises important ethical questions about the true cost of unification—what has been sacrificed in the name of global cooperation?

From my perspective, the unification of humankind is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it has allowed for the incredible achievements of modern civilization—technological advances, cultural exchange, and unprecedented levels of material wealth. On the other hand, it has also fostered a sense of disconnection, as local communities are subsumed into the larger global marketplace.

Harari’s analysis forces us to confront this duality and to ask ourselves whether the benefits of globalization outweigh its costs.

Factually, Harari’s exploration of the unification of humankind paints a complex picture of human history.

It is a story of both triumph and loss, of the remarkable ability of our species to cooperate on a global scale, but also of the inevitable tensions that arise when diverse cultures are forced into a single system. Money, empire, and religion have all played their part in this drama, but the final act is still being written.

From my own perspective, this unification has a deeply human element. It is the story of our species’ relentless drive to connect, to communicate, and to find common ground—even when that common ground is as abstract as money or as intangible as faith. Yet, it is also a cautionary tale about the fragility of the systems that bind us together.

In a world where everything is for sale, we must remember that not all things of value can be bought. As Harari so eloquently reminds us, the unification of humankind is not just an economic or political process—it is a profoundly human one.

3. The Scientific Revolution

The rise of modern science has shaped human understanding and control over the world for the past 500 years, transforming society and enabling unprecedented technological advances. This period, known as the Scientific Revolution, shifted humanity’s approach from ancient certainties to a future defined by progress, inquiry, and innovation.

Discovery of Ignorance

Harari eloquently suggests that one of the most profound shifts in human thinking during the Scientific Revolution was the “discovery of ignorance.”

Before the Scientific Revolution, humans believed in a complete set of knowledge derived from religious texts and ancient traditions. Whether one was a scholar in medieval Europe or a peasant in the Islamic Golden Age, the prevailing attitude was that the most critical truths were already known, revealed by divine forces or the enlightened individuals of history.

For instance, if a medieval European peasant were asked how the world began, the answer would likely come from biblical scripture, not curiosity or scientific investigation.

The realization that we do not know everything, and more importantly, that what we think we know could be entirely wrong, ignited a new era of inquiry.

The Latin phrase “ignoramus” (we do not know) became a cornerstone of modern science. Harari emphasizes how this simple yet radical admission catalyzed a wave of exploration and discovery. As he puts it, “The great discovery that launched the Scientific Revolution was the discovery that humans do not know the answers to their most important questions”.

For me, this idea resonates deeply with modern existential struggles. In a world filled with uncertainties, from climate change to artificial intelligence, the lesson of the Scientific Revolution reminds us that embracing our ignorance is not a flaw but the first step toward genuine progress.

Our ancestors’ willingness to admit their lack of knowledge birthed modern science and, by extension, the modern world itself. It is this recognition that leads us to ask new questions and seek answers in the face of our greatest challenges.

The Unison of Science and Empire

Harari argues that scientific advancement was inextricably tied to empire-building. The two forces fed into each other, creating a “feedback loop” that propelled both forward.

Empires sought knowledge to gain power, while scientists relied on imperial resources to conduct their research. Harari presents this bond as a driving force behind the European conquest of distant lands and the expansion of global trade.

This relationship is exemplified in the 18th-century scientific expeditions sponsored by European powers. The British Royal Society‘s investment in Charles Green’s journey to observe the transit of Venus in the South Pacific is a perfect example.

What began as a scientific inquiry into the distance between the Earth and the Sun turned into a broader imperial project of mapping, classifying, and controlling distant lands. Science thus became a tool of conquest, as discoveries led to greater military and economic dominance.

From my perspective, this confluence of science and power reveals an unsettling aspect of human progress. While the pursuit of knowledge is noble, it is also fraught with ethical dilemmas. The very science that allows us to understand the universe can also be used to dominate and exploit.

Even today, we see this dynamic at play in the race for technological supremacy, with nations vying for control over innovations in artificial intelligence, space exploration, and biotechnology. It is a reminder that scientific progress is never neutral—it is always shaped by the political and economic systems that support it.

Technological Advancements and the Future of Homo Sapiens

The Scientific Revolution set humanity on a path toward technological dominance over nature.

Harari notes how early modern science was not satisfied with mere theories; it sought practical applications that would expand human power. This ambition culminated in the creation of technologies that have radically transformed life on Earth, from industrial machinery to nuclear weapons.

One of the most poignant examples Harari gives is the atomic bomb, which symbolized both the immense potential and the existential danger of scientific advancement. As Robert Oppenheimer, the physicist behind the bomb, famously quoted from the Bhagavad Gita after witnessing the first test explosion: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds”.

This statement captures the paradox of modern science: it has the power to save lives and improve the human condition, but it also holds the capacity to destroy civilization.

In today’s world, we face new frontiers of scientific discovery that bring with them similarly profound ethical questions.

Artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, and biotechnologies offer us the promise of reshaping our species and conquering age-old problems like disease and hunger. However, they also carry risks that could redefine what it means to be human. As Harari points out, Homo sapiens might one day be replaced by genetically engineered superhumans or intelligent machines.

Personally, I find the trajectory of technological advancements both exhilarating and terrifying. The idea that science could one day render our species obsolete is both a thrilling and disconcerting prospect.

As we continue to push the boundaries of what is possible, we must grapple with the moral implications of our creations. What kind of world do we want to build, and how do we ensure that the benefits of science are shared by all, rather than concentrated in the hands of the powerful? The lessons of the Scientific Revolution—its optimism, ambition, and unintended consequences—offer a cautionary tale for the future.

The Scientific Revolution was not merely a revolution of knowledge; it was a revolution of power and possibility. By admitting ignorance, humanity unlocked the potential for boundless discovery. But as Harari reminds us, this new power comes with significant responsibility.

The tools we create have the potential to reshape the world—for better or for worse.

As we stand at the precipice of a new era defined by artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, and biotechnological advancements, the lessons of the Scientific Revolution remain more relevant than ever.

In the end, it is our collective responsibility to use science wisely, not just for the advancement of our species but for the preservation of life itself. Just as the early scientists questioned the certainties of their age, we too must be willing to question the direction in which our technological progress is taking us.

The Scientific Revolution taught us the importance of curiosity and inquiry, but it also taught us the dangers of unchecked ambition. It is up to us to find a balance that ensures our future remains bright.

Final Thoughts

Reflecting on Harari’s ideas, one cannot help but marvel at the profound impact of these cognitive shifts.

The Cognitive Revolution reminds us that what separates humans from other animals is not just our intelligence but our capacity for imagination.

We are storytellers, constantly weaving narratives about who we are, where we come from, and where we are going. The myths we create—whether they be religious, political, or cultural—shape our societies in ways we often take for granted. What started as small bands of hunter-gatherers exchanging gossip and crafting rudimentary tools has blossomed into vast networks of global cooperation, rooted in shared beliefs and collective fictions.

Harari’s exploration of the Cognitive Revolution serves as a reminder that human civilization is built on fragile constructs.

Our religions, our laws, our economies are all figments of human imagination, yet they hold immense power because we collectively believe in them. As Harari notes, the power of Homo sapiens lies not in the individual, but in the collective imagination.

It is this ability to imagine, create, and believe in shared myths that has allowed our species to rise above others.

It shows how a species that once scavenged bones for marrow became the dominant force on the planet, not through brute strength, but through the power of imagination and shared belief.

Harari’s work invites us to consider how much of what we hold dear—our identities, our nations, our religions—are, at their core, shared stories that allow us to live, work, and dream together.

However, The Cognitive Revolution’s central gift—the ability to create and share fictions—has a direct parallel in AI’s ability to simulate human thought. Harari’s notion that Homo sapiens achieved dominance by believing in collective fictions raises a fascinating question: Can machines contribute to these myths? AI systems like GPT-4 assist in storytelling, translating abstract ideas into coherent narratives, much as early humans did around campfires. The AI systems are doing much more than any competent and intelligent human being, already.

For instance, consider the role of AI in digital marketing. Companies craft narratives about their brands—“myths” that resonate with consumers on an emotional level. In a way, AI has become a co-storyteller, shaping modern myths in ways Harari might find a natural extension of the human cognitive leap.

The ability to cooperate flexibly with strangers, as Harari emphasizes, was enabled by shared myths.

Today, this principle extends to how humans interact with AI. Collaboration with machines—whether via virtual assistants or collaborative design software—echoes the dynamic of early human tribes working together to achieve shared goals.

The myths, however, have shifted: instead of gods or spirits, we now place trust in algorithms and data systems.

Harari’s observation that myths enabled humans to build societies also applies to modern consumerism. Digital marketing harnesses the power of storytelling to sell products and ideas. For instance, Nike’s “Just Do It” is more than a slogan—it’s a modern myth that equates athletic achievement with personal empowerment.

AI tools that analyze consumer behavior and tailor messages have become the new shamanic storytellers, guiding global tribes toward shared aspirations. Read 10 Groundbreaking AI Books That Will Inspire Hope and Fear and Help You Survive the AI Revolution!

The Cognitive Revolution reveals a bittersweet truth about Homo sapiens. Our dominance was not inevitable; it was an accident of evolution.

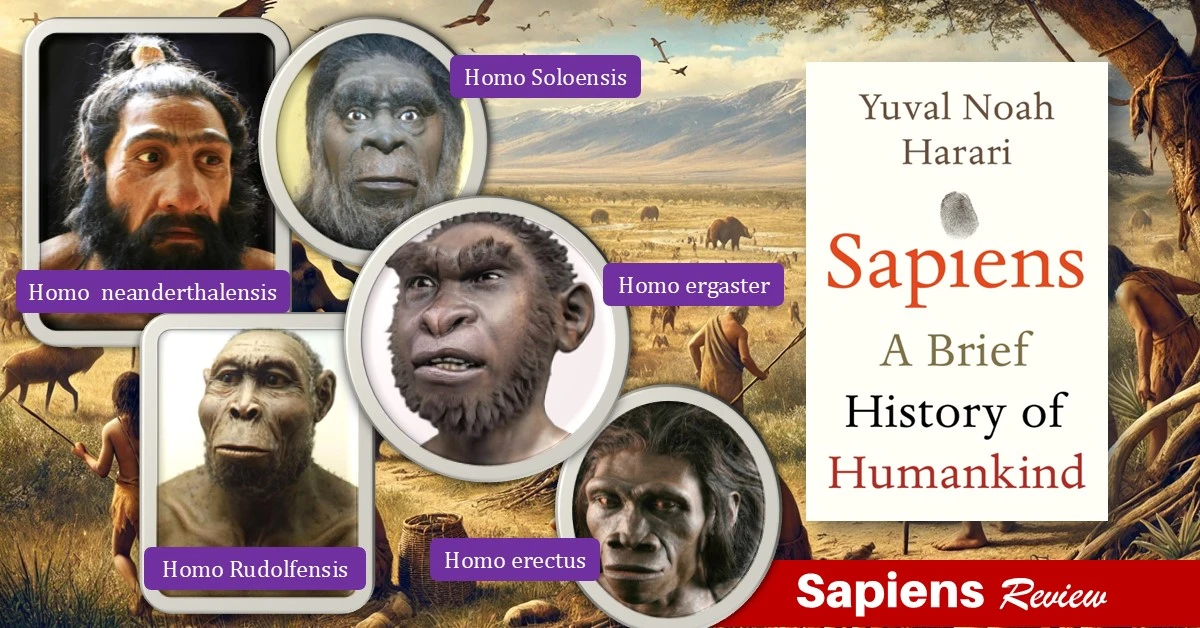

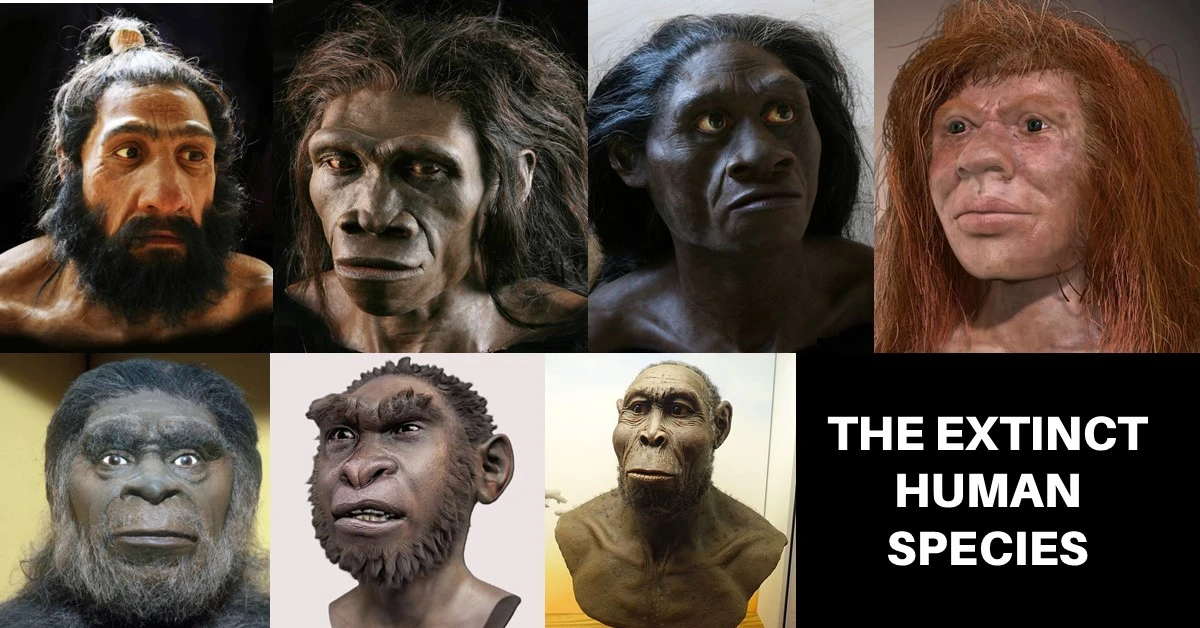

Harari’s reflection on how we destroyed other human species— Homo neanderthalensis (‘Man from the Neander Valley), popularly referred to simply as ‘Neanderthals’, Homo erectus, ‘Upright Man’, Homo soloensis, ‘Man from the Solo Valley’, Homo floresiensis, ‘man from Flores Island of Indonesia”, Homo denisova, ‘man from Denisova cave’, Homo rudolfensis, ‘Man from Lake Rudolf’ and Homo ergaster, ‘Working Man’. —is a sobering reminder of our capacity for both collaboration and annihilation. Today, as we confront ethical dilemmas surrounding AI and genetic engineering, we must ask: Are we repeating the cycle of dominance at the expense of diversity?

I like the idea of Harari that

“It’s a common fallacy to envision these species as arranged in a straight line of descent, with Ergaster begetting Erectus, Erectus begetting the Neanderthals, and the Neanderthals evolving into us. This linear model gives the mistaken impression that at any particular moment only one type of human inhabited the earth and that all earlier species were merely older models of ourselves. The truth is that from about 2 million years ago until around 10,000 years ago, the world was home, at one and the same time, to several human species. And why not?

Today there are many species of foxes, bears and pigs. The earth of a hundred millennia ago was walked by at least six different species of man. It’s our current exclusivity, not that multi-species past, that is peculiar – and perhaps incriminating. As we will shortly see, we Sapiens have good reasons to repress the memory of our siblings.”

Harari’s text urges us to consider how adaptability, shared myths, and communication remain our species’ defining features. They enabled us to conquer the world, but they also demand responsibility. Whether we’re crafting AI systems or addressing existential threats, the Cognitive Revolution’s lessons remain profoundly relevant.

Food Security, Sustainability, and Biotechnology

The legacy of the Agricultural Revolution reverberates into the present, shaping contemporary debates on food security, sustainability, and the future of agriculture.

Modern agricultural practices, with their reliance on industrial methods, chemical fertilizers, and monocultures, echo the foundational shifts of 10,000 years ago. These systems have produced unprecedented food surpluses but at immense environmental and ethical costs. Harari’s observation that “the agricultural economy was based on a seasonal cycle of production” still applies, albeit now on an industrial scale.

Today, the challenges of climate change, biodiversity loss, and soil degradation demand a rethinking of agricultural paradigms.

Harari’s critique of the Agricultural Revolution serves as a cautionary tale against uncritical reliance on technology and short-term gains. As biotechnology and genetic engineering promise new solutions—from drought-resistant crops to lab-grown meat—we must grapple with the ethical and ecological implications.

Will these innovations liberate humanity from the “luxury trap” of agriculture, or will they entangle us further in its complexities?

The urgency of these questions underscores the enduring relevance of Harari’s insights. The Agricultural Revolution may have set humanity on an irreversible path, but it also offers lessons in humility and foresight. As Harari concludes, “Humanity’s search for an easier life released immense forces of change that transformed the world in ways nobody envisioned or wanted”. This recognition invites us to approach the future of agriculture—and our relationship with the Earth—with caution, empathy, and a commitment to sustainability.

As I write these reflections, I am struck by the enduring resilience and ingenuity of Homo sapiens. Yet I am also reminded of our fragility and interconnectedness with the natural world.

The Agricultural Revolution was not merely a chapter in human history; it was a turning point that reshaped our destiny. Its lessons—of caution, humility, and adaptability—are more urgent than ever in an age of rapid technological change and ecological uncertainty.

Globalization, Cultural Homogenization, and Digital Currencies

The themes of unification remain acutely relevant in our contemporary world. Globalization mirrors the historical processes Harari describes, albeit on a technologically accelerated scale.

The global economy, powered by digital currencies and international trade, reflects the universal trust system that money established millennia ago. Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are perhaps the modern incarnation of money’s ability to transcend national and cultural boundaries, relying solely on collective belief in blockchain systems.

Cultural homogenization, another result of unification, is evident in the worldwide proliferation of Western norms, languages, and technologies.

Harari’s observation that empires often created hybrid cultures rings true today. The “global empire” we live in, driven by a multi-ethnic elite of entrepreneurs and technocrats, resembles earlier imperial structures but without a single centralized power.

Religions, though less dominant in governance, still influence global unity and conflict. Harari’s analysis reminds us that the tensions between shared religious ethics and secular governance shape debates on morality, law, and human rights.

Ethical Debates in AI, Biotechnology, and Transhumanism

The legacies of the Scientific Revolution are vividly alive in contemporary debates about artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and transhumanism.

Harari draws attention to the ethical quandaries that arise from bioengineering and cyborg technologies. He speculates on scenarios where human desires, emotions, and cognitive abilities could be engineered, leading to beings fundamentally different from Homo sapiens. Such transformations challenge the very definition of humanity. As Harari provocatively asks, “What do we want to become?”

These questions are not confined to philosophical musings but have real-world implications. The rise of personalized medicine—enabled by advancements in genomics—poses questions about privacy and equity.

Harari discusses how mapping the human genome, once a Herculean task requiring billions of dollars, has become accessible for a fraction of the cost, opening the door to tailored treatments. Yet, this progress is fraught with concerns: “Would insurance companies be entitled to ask for our DNA scans? Would employers have the right to prefer candidates with ‘better’ genetics?”.

The implications of transhumanism extend even further. Harari warns of a future where humans might engineer themselves into a new species, effectively bringing Homo sapiens to an end. “Tinkering with our genes won’t necessarily kill us. But we might fiddle with Homo sapiens to such an extent that we would no longer be Homo sapiens,” he writes, underscoring the existential stakes of these developments.

Reading Harari’s exposition on the Scientific Revolution is a humbling experience. It forces us to confront our collective hubris—our belief that progress is inherently virtuous and that technological mastery equates to moral wisdom. Harari’s narrative is replete with cautionary tales, from the atomic bomb to bioengineered creatures.

These examples serve as reminders that science is a double-edged sword, capable of both immense good and irreversible harm.

As a human reflecting on these developments, I am struck by the paradox of our species. We are both creators and destroyers, driven by curiosity yet often blind to the consequences of our actions. Harari’s work challenges us to wield our scientific prowess with humility and foresight.

It is not enough to ask what we can achieve; we must also ask what we should achieve.

Key Themes: Intelligent Design and the Rise of Post-Human Species

The text highlights the departure from Darwinian natural selection, asserting that life might soon be governed by intelligent design.

Harari notes, ” For close to 4 billion years, every single organism on the planet evolved subject to natural selection. Not even one was designed by an intelligent creator. The giraffe, for example, got its long neck thanks to competition between archaic giraffes rather than to the whims of a super-intelligent being. Proto-giraffes who had longer necks had access to more food and consequently produced more offspring than did those with shorter necks…. The beauty of Darwin’s theory is that it does not need to assume an intelligent designer to explain how giraffes ended up with long necks…. It is now beginning to break the laws of natural selection, replacing them with the laws of intelligent design”.

This is a pivotal realization: for millennia, humanity adapted to the whims of nature; now, it possesses the tools to shape life itself.

The concept of intelligent design here is neither theological nor speculative—it is an acknowledgment of humanity’s growing capacity to engineer life. Harari cites three avenues through which this transformation could manifest: biological engineering, cyborg engineering, and the creation of inorganic life. These paths, he suggests, could lead to the rise of beings so radically different from Homo sapiens that they may no longer be considered human.

The book also discusses the artistic and symbolic representation of this shift. Eduardo Kac’s green fluorescent rabbit, Alba, created through genetic engineering, serves as a harbinger of the age of intelligent design. This example encapsulates both the power and the disquieting implications of humanity’s newfound ability to create life forms that defy the natural order.

In the context of contemporary science, Harari’s reflections resonate profoundly. The development of CRISPR and other genetic engineering tools has turned the manipulation of DNA into an almost routine laboratory activity. Harari’s assertion that “life will be ruled by intelligent design” finds chilling validation in today’s headlines, where scientists edit human embryos and create genetically modified organisms with precision.

The ethical dilemmas posed by such technologies are equally pertinent. Harari warns of the rise of a superhuman elite, suggesting that “our late modern world prides itself on recognizing the basic equality of all humans, yet it might be poised to create the most unequal of all societies”. These observations challenge humanity to consider whether these advancements will widen social divides or lead to unprecedented forms of discrimination based on biological enhancements.

Additionally, Harari’s concerns about superintelligence align with current debates about artificial intelligence.

While AI today remains far from the godlike entities he envisions, the rapid pace of development suggests that the emergence of machines with superior cognitive and emotional capacities is not a question of “if” but “when.” Harari speculates that such beings could look at humanity as condescendingly as humans view Neanderthals.

Harari’s exploration of these themes is as much a philosophical inquiry as it is a scientific prediction. He raises existential questions that strike at the heart of what it means to be human: “What do we want to become?” he asks, urging readers to confront their collective aspirations and fears. This question is not merely rhetorical but an invitation to ponder the moral and ethical frameworks that should guide the creation of post-human species.

The author also cautions against complacency. Just as no one in the early 20th century foresaw the internet, the long-term implications of genetic and technological innovations are likely beyond our current imagination.

Harari evokes Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to illustrate humanity’s fear of its own creations, suggesting that the real terror lies not in creating monsters but in being replaced by entities vastly superior to ourselves.

As we stand at the crossroads of history, the question of what it means to be human becomes more pressing than ever. Humanity has evolved from foraging bands to planetary conquerors, yet we have done so with devastating consequences to our environment and the very species with which we share this planet. Harari’s exploration of the human journey reveals how, at every stage, Homo sapiens has radically altered the world—often with irreversible effects.

From the extinction of megafauna due to hunting and fire agriculture to the industrial exploitation of animals and resources, our species has consistently prioritized its own needs above all else.

This history forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth: our progress has often been built on the suffering of others—both human and non-human alike.

“Over the last few decades, we have been disturbing the ecological equilibrium of our planet in myriad new ways, with what seem likely to be dire consequences”. The Anthropocene, this new epoch defined by human impact, carries with it a heavy responsibility. As Harari warns, “we are destroying the foundations of human prosperity in an orgy of reckless consumption”. Our legacy will not only be one of extraordinary technological achievements but also one of environmental degradation, species extinction, and social fragmentation.

What Now!

We must now ask ourselves: what kind of future do we want to create? Harari urges us to consider this crucial question as one of the final generations of Homo sapiens before we potentially evolve into something else entirely.

The decisions we make today will echo through the centuries. It is imperative that we reflect on the long-term consequences of our actions, not just for ourselves but for future generations and the planet as a whole.

Each of us has a role to play in this transformation. Whether through conscious consumption, active participation in political systems, or simply by reconnecting with the natural world, we have the power to shape the narrative of the Anthropocene.

Let us critically examine our collective actions—how they affect not only the environment but also our social structures and moral frameworks. Harari’s work invites us to imagine a future in which we restore balance, recognizing that our well-being is inseparable from the health of the planet and the creatures that inhabit it.

In the end, we are tasked with answering the most important question of all: what do we want to become? Let us choose wisely, with humility and foresight, for the fate of humanity and the Earth rests in our hands.

The Timeline of Human History Based on Sapiens

Pre-Human History

–13.5 billion years ago – The Big Bang: Matter and energy appear.

– 4.5 billion years ago – Formation of planet Earth.

– 3.8 billion years ago – First life forms appear.

Early Human Evolution

– 6 million years ago – Last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees.

– 2.5 million years ago– Evolution of the Homo genus and first stone tools.

– 2 million years ago – Humans migrate from Africa to Eurasia.

– 500,000 years ago – Neanderthals evolve in Europe and the Middle East.

– 300,000 years ago – Daily use of fire begins.

– 200,000 years ago – Homo sapiens evolves in East Africa.

The Cognitive Revolution (c. 70,000 BCE)

– 70,000 years ago – Humans develop advanced language and abstract thinking.

– 45,000 years ago – Homo sapiens reaches Australia; extinction of Australian megafauna.

– 30,000 years ago – Neanderthals go extinct.

– 16,000 years ago – Humans settle in the Americas, leading to the extinction of American megafauna.

– 13,000 years ago – Homo sapiens becomes the sole surviving human species.

The Agricultural Revolution (c. 12,000 BCE)

– 12,000 years ago – Domestication of plants and animals, leading to permanent settlements.

– 5,000 years ago – First kingdoms, script, and money emerge; polytheistic religions develop.

The Unification of Humankind

– 4,250 years ago – The first empire: Akkadian Empire of Sargon.

– 2,500 years ago – Invention of coinage and rise of universal empires (e.g., Persian Empire) and religions (e.g., Buddhism).

– 2,000 years ago – The Han Empire in China, The Roman Empire in the Mediterranean, spread of Christianity.

– 1,400 years ago – Rise of Islam.

The Scientific Revolution (c. 1500 CE – Present)

– 500 years ago – Humankind admits its ignorance, leading to the rise of science.

– 200 years ago – The Industrial Revolution; rise of capitalism, global markets, and mass extinctions.

Modern and Future Possibilities

– The present – Nuclear weapons threaten humanity, space travel begins, and genetic engineering shapes organisms.

– The future? – Homo sapiens could be replaced by superhumans through intelligent design.

This timeline follows Harari’s broad overview of human history, showing the major revolutions that shaped our species.

10 Lessons

After reviewing Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, by Yuval Noah Harari, I have distilled 10 profound lessons, framed from a deeply human and intellectual perspective. These lessons capture the essence of humanity’s journey, our triumphs, and our shortcomings, emphasizing the evolutionary, cultural, and existential aspects of human civilization.

1. The Power of Collective Fiction

At the heart of human society lies the ability to create and believe in collective myths—fictions that enable large groups to cooperate in a way no other species can. Harari profoundly observes, “Homo sapiens is a storytelling animal”.

Myths such as religion, nations, and money hold no physical reality, yet they possess an undeniable power to mobilize societies, shaping history’s trajectory.

2. The Cognitive Revolution

Harari posits that Homo sapiens gained supremacy not through brute strength but through language, enabling flexible, large-scale cooperation. This revolution, approximately 70,000 years ago, allowed sapiens to outcompete other human species and animals, redefining the boundaries of possibility.

3. The Agricultural Trap

One of the most profound insights is Harari’s labeling of the Agricultural Revolution as “History’s Biggest Fraud”. While agriculture led to the rise of civilizations, it came at the cost of human health, happiness, and social equality.

The sedentary lifestyle introduced by farming led to an overproduction of food and wealth, but also to hierarchy, wars, and exploitation.

4. The Illusion of Happiness in Modern Times

Harari’s exploration of happiness touches the core of human existence. He remarks that even with modern technology and comforts, human happiness has not necessarily improved. In fact, despite material abundance, the pursuit of happiness remains elusive, as shown through historical and psychological analysis.

5. Money: The Great Unifier

Money, Harari argues, is the most universal and efficient system of mutual trust ever devised. More than religion or politics, it unites people across cultures. Harari’s notion that “people who do not believe in the same god or obey the same king are more than willing to use the same money” encapsulates the power of currency as a human construct.

6. The Arrow of History: Towards Unity

History, Harari claims, moves in the direction of unity. While cultures may diverge temporarily, over millennia they coalesce into larger, more complex entities. Today’s interconnected global society is the culmination of this relentless march towards unification.

7. Imperialism and Cultural Legacy

Empires, Harari suggests, built much of the world’s current culture, even though they were often founded on violence and exploitation. Yet, their legacies shape our modern identities, languages, and political boundaries.

The enduring nature of empires is evident in modern values, laws, and governance.

8. The Birth of Science

The Scientific Revolution, Harari asserts, began with the realization of human ignorance. By admitting that we didn’t know everything, humanity opened the door to discovery and progress, giving birth to modern science. This intellectual humility fueled the pursuit of knowledge and transformed the world.

9. The Creed of the Modern Age

Harari’s analysis of capitalism as a modern creed emphasizes how faith in future economic growth has come to dominate global thought. Capitalism, he explains, allows societies to trust in imagined future wealth, creating a dynamic system of credit that fuels technological and industrial revolutions.

10. Humanity’s Fragile Ego

One of the most introspective lessons of Sapiens is humanity’s rapid rise to the top of the food chain, which Harari suggests led to a deep-seated sense of insecurity. Unlike lions or sharks, which evolved to the top over millions of years, Homo sapiens reached the apex in a blink of evolutionary time, resulting in existential anxieties and profound cruelty.

Conclusion

Reflecting on Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, I find myself both awed and unsettled. Yuval Noah Harari does not merely recount history—he dissects it with surgical precision, exposing the myths, constructs, and forces that have shaped our species.

What makes this book so profoundly enlightening is its ability to strip away the comforting narratives we tell ourselves and reveal the often-uncomfortable truths beneath.

Yet, perhaps the most terrifying aspect of Sapiens is not just the history it presents but the future it implies. If Homo sapiens have been able to reengineer their societies, economies, and even their own biology through shared myths, what happens when we take this power to its logical extreme?

Are we on the brink of transcending our humanity, or will we engineer our own downfall?

Sapiens forces us to confront difficult questions about our past and, more importantly, our future. While some may find solace in the grand narrative of human progress, others will walk away deeply unsettled, realizing that we are a species blindly shaping a world without fully understanding the consequences.