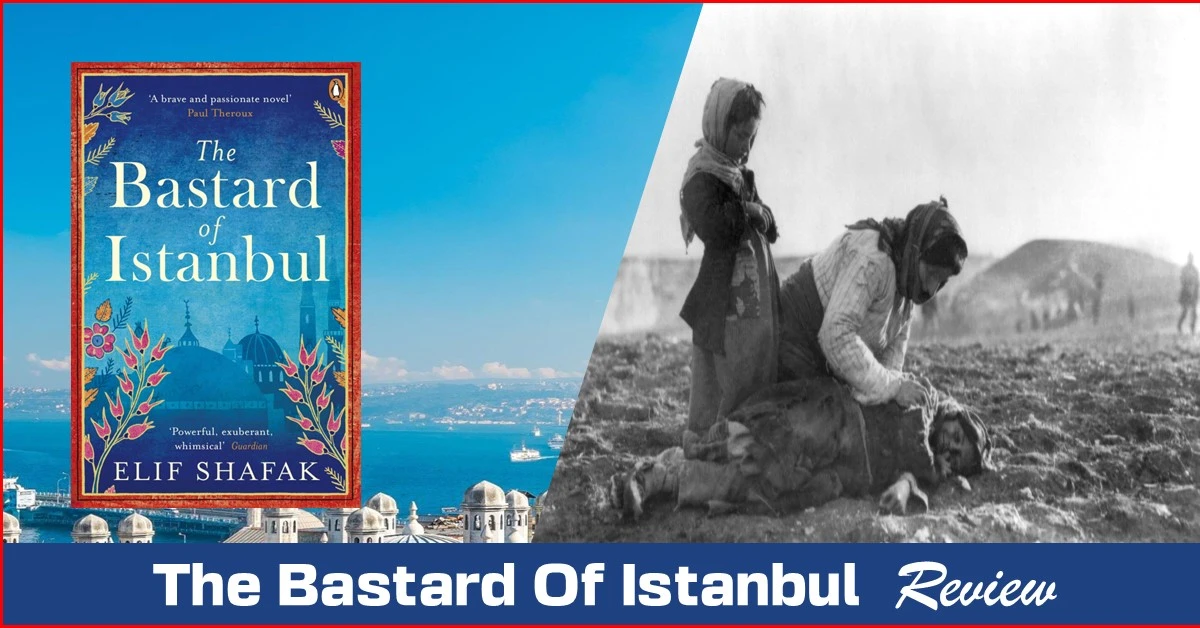

The Bastard of Istanbul by Elif Shafak is a profound narrative that intertwines the personal with the political, the familial with the national, and the past with the present. It is a novel that speaks not only to the intricacies of identity but also to the haunting weight of history—specifically, the collective memory of the Armenian genocide.

Through its characters, primarily Zeliha Kazancı and Asya Kazancı, the book explores the lives of two interconnected families—one Turkish and the other Armenian-American.

Elif Shafak’s novel sparked intense reactions, not only for its ambitious narrative but also for its exploration of deeply sensitive historical wounds. Critics like Geraldine Bedell from The Guardian acknowledged the importance of the book in drawing attention to the Armenian Genocide and the complex emotions it evoked in Turkey. Along with forced Islamization of the living, one million Armenian people were killed during the genocide by the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey.

Bedell described the book as “exuberant and teeming,” while also noting its chaotic energy, likening the experience of reading it to holding a bag of angry cats.

Meanwhile, Lorraine Adams of The New York Times critiqued Shafak’s ability to balance her moral compulsion with literary finesse, suggesting that her ambition outpaced her artistic execution.

Despite this, both critics recognized the boldness of Shafak’s themes, which unapologetically exposed deep societal rifts, particularly concerning free speech and national identity.

Shafak’s literary endeavor also led her to a harrowing courtroom battle. In 2006, she was put on trial under Article 301 of the Turkish Penal Code, accused of “insulting Turkishness” for her portrayal of the Armenian Genocide.

Nationalist lawyer Kemal Kerinçsiz led the charge against her, accusing Shafak of undermining national pride. The trial garnered international attention, with figures like Joost Lagendijk attending in support of Shafak. Although the case was ultimately dismissed due to insufficient evidence, the ordeal highlighted the fragile state of free expression in Turkey.

It marked a pivotal moment, not just for Shafak’s career, but for the broader conversation on artistic freedom and historical accountability in the country.

However, both The Forty Rules of Love by Elif Shafak and The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini explore themes of love, redemption, and the transformative power of forgiveness, but through different cultural and spiritual lenses.

In The Forty Rules of Love, Shafak intertwines the mystical journey of Rumi and Shams of Tabriz with a modern woman’s search for spiritual awakening, emphasizing love as a divine, all-encompassing force that transcends human limitations.

Similarly, The Kite Runner delves into Amir’s quest for redemption after betraying his childhood friend Hassan, showing how guilt can lead to a lifetime of inner torment, and only through love and atonement can healing occur. Both novels explore how individuals can transform their lives through love and forgiveness—whether it’s divine love in The Forty Rules of Love or personal redemption in The Kite Runner—highlighting the universal human need for compassion, connection, and spiritual growth.

Plot Summary

The Bastard of Istanbul, written by Elif Shafak, intertwines the lives of two families, one Turkish and the other Armenian American, deeply connected through historical tragedies and hidden secrets. The novel primarily centers around Asya Kazancı, a rebellious, nihilistic young woman growing up in an all-female household in Istanbul, and her counterpart, Armanoush Tchakhmakhchian, an Armenian American who embarks on a journey to discover her heritage.

Asya, who is raised without a father and struggles with her identity as a “bastard,” represents the voice of modern Turkey. Her family is unconventional, dominated by women—her aunts and grandmother—all of whom have their own quirks and secrets. The past weighs heavily on the family, particularly the long-lost son, Mustafa, who returns to Istanbul with his American wife, Rose.

Armanoush, meanwhile, is split between her American mother and her Armenian father’s family. She feels the burden of her Armenian roots, especially the trauma of the Armenian Genocide, and decides to travel to Istanbul in search of understanding. In Istanbul, she stays with the Kazancı family and forms a deep bond with Asya, despite their different backgrounds.

As the novel progresses, layers of family history unravel, revealing dark secrets that link both families, hinting at shared guilt and collective memory.

The story emphasizes the generational trauma experienced by Armenians and Turks, urging readers to confront the past. Shafak masterfully explores themes of identity, memory, and forgiveness, while portraying Istanbul as a central character—alive with its complexity and contradictions.

The book’s emotional heart lies in the confrontation of these painful histories and the possibility of reconciliation, symbolized through the bond between Asya and Armanoush. Through humor, mysticism, and tragedy, Shafak weaves a narrative of self-discovery and the inescapable weight of the past.

Analysis

From the very first chapter, the novel draws readers into Istanbul’s chaotic yet deeply enchanting atmosphere. Zeliha, who opens the novel, is a striking character, a rebellious and bold woman in a deeply traditional society.

She lives with her extended family in a crumbling old house in Istanbul, embodying the complexities of Turkish womanhood. Her experiences reflect a sense of defiance—against patriarchy, against the conservative expectations of her society, and against the ghosts of the past. She swears at the rain, curses her cobblestones, and refuses to fit neatly into the role society expects of her. Yet, as the narrative progresses, we see that Zeliha, like the city she inhabits, is haunted by unresolved histories.

Her unwanted pregnancy, and later decision to raise Asya as a single mother, mirrors Istanbul’s own complicated relationship with the forgotten and buried parts of its past.

The concept of ‘amnesia’—both personal and collective—is a recurring motif in the novel. Turkey’s unwillingness to acknowledge the Armenian genocide is paralleled with the Kazancı family’s refusal to confront their own traumas. Shafak masterfully blurs the lines between personal memory and national history.

There’s a line from the book that particularly struck me: “It is a sin to forget, as much as it is to remember.” This tension between remembering and forgetting is what lies at the heart of the novel. Characters like Asya, the “bastard” of the family, and Armanoush, an Armenian-American young woman seeking answers about her heritage, are searching for truths—truths that their elders have tried to bury.

Armanoush’s journey to Istanbul is not just a physical journey but a metaphorical quest to reclaim a stolen history. Her interactions with the Kazancı family—and especially with Asya—reveal the depth of the inherited trauma that both Armenians and Turks carry.

Yet, it’s Asya’s nihilism, her disbelief in both the past and the future, that offers a compelling contrast. Asya is an atheist and a cynic, the embodiment of Istanbul’s modernity and disillusionment. Her sense of detachment from both her family and her country’s history can be seen as a coping mechanism in a city that refuses to look back. She represents a generation that struggles with the weight of history, unsure whether to embrace or reject it.

Istanbul itself is more than just a setting in this novel—it is a character in its own right. The city is both timeless and transient, ancient and modern. Shafak’s rich, sensory descriptions of Istanbul make it feel alive. From the chaotic streets to the bustling bazaars, the rain-soaked alleyways to the quiet, sacred mosques, Istanbul pulses throughout the novel, shaping the lives of its characters.

In one passage, Zeliha walks through a rainstorm, cursing the very streets she loves: “Rain is an agony here… It’s mud and chaos and rage, as if we didn’t have enough of each already.” The city reflects the emotional turmoil of the characters—a place of contradictions, where beauty and pain are inextricably linked.

Shafak also uses food as a way to explore cultural identity. Each chapter is named after an ingredient used in Turkish or Armenian cuisine, symbolizing the ways in which culture, like food, is passed down through generations. It is through the shared rituals of cooking and eating that these characters connect across their cultural divides. The Kazancı family’s meals are almost sacred, spaces where generations of women come together, both to nurture and to fight.

This leads to one of the novel’s most compelling aspects—its portrayal of women. The Kazancı household is a matriarchy, filled with strong, flawed, and deeply human women.

From Banu, the mystic who communicates with djinns, to Petite-Ma, the elderly grandmother who clings to superstitions, the women of this family are bound together by tradition, love, and shared secrets. Yet, they are also fiercely independent, each grappling with their own demons. The absence of men in the Kazancı household is significant—Shafak seems to suggest that the future of both Turkey and Armenia rests in the hands of women, who have the power to break the cycles of silence and denial.

The Bastard of Istanbul is a novel that lingers long after the last page. It is a story about identity, about the stories we tell ourselves to survive, and about the painful process of confronting the past. Shafak’s writing is lyrical, yet grounded in the emotional realities of her characters.

It is impossible to read this novel without being moved by the weight of history it carries, and by the hope it offers for reconciliation and healing. As someone deeply interested in the intersections of personal and collective memory, I found this novel to be a poignant reflection on the power of stories—both the ones we inherit and the ones we choose to tell.

Lessons from The Bastard of Istanbul

Elif Shafak’s The Bastard of Istanbul is a novel brimming with lessons on memory, identity, family, and the intricacies of cultural inheritance. Through the richly layered lives of its characters, Shafak addresses themes that challenge both the personal and the political. Below are some of the core lessons the novel imparts, along with notable quotes from the text that amplify these insights.

1. The Weight of History

One of the most striking lessons from The Bastard of Istanbul is the enduring weight of history, both on individuals and nations.

Shafak juxtaposes Turkey’s denial of the Armenian genocide with the Kazancı family’s personal refusal to confront their own past traumas. The novel teaches that ignoring or forgetting history does not erase its impact; it continues to shape the present.

As Shafak writes, “It is a sin to forget, as much as it is to remember.” This quote encapsulates the paradox of memory. The novel suggests that while remembering painful histories can be excruciating, it is necessary for healing and reconciliation.

To forget, on the other hand, is to deny those who suffered and those who seek justice.

2. Family Ties and Shared Trauma

Another important lesson from the novel is how families—like nations—carry shared trauma. The Kazancı and Armenian-American families, though worlds apart, are bound by a collective inheritance of suffering and silence.

Family dynamics in the novel reveal that trauma can be passed down through generations, even when unspoken.

Zeliha’s relationship with her daughter, Asya, highlights this intergenerational burden. Zeliha’s decision to raise Asya as a single mother after attempting to abort her reflects the complicated choices women make under societal pressures.

The novel underscores how family secrets can corrode relationships if left unacknowledged, reminding us that honesty and confrontation are vital in healing familial wounds.

A resonant line in the book illustrates this point: “What was the use of giving a voice to the mute past? It was better left untouched, unwoken. Otherwise, it was going to be louder than the present, louder than the future.” This is a reminder that uncovering buried truths, though difficult, is crucial for personal and collective liberation.

3. Identity and the Search for Belonging

The Bastard of Istanbul also offers profound insights into the search for identity. Asya, the novel’s titular “bastard,” is a young woman who feels disconnected from both her family and her country. Her rejection of religion, her nihilism, and her questioning of cultural norms reflect the internal conflict of those who feel they do not belong.

Asya’s struggles underscore the complexity of modern identity, especially in a globalized world where cultural, familial, and national identities often clash.

In contrast, Armanoush, an Armenian-American character, embarks on a journey to Istanbul to reconnect with her roots. Her quest to uncover the truth about her heritage highlights the importance of knowing one’s history in the search for self-understanding. The novel suggests that identity is not fixed but fluid, shaped by personal experiences and historical contexts.

A powerful quote that reflects this idea is: “Who we are cannot be separated from where we come from, even if we do not know the details of that place.” Here, Shafak emphasizes that our identities are deeply intertwined with our pasts, whether we acknowledge them or not.

4. The Power of Women and Matriarchy

At the heart of The Bastard of Istanbul is a powerful exploration of matriarchy and female strength. The Kazancı family is dominated by strong, complex women who defy traditional gender roles. These women, each flawed and remarkable in their own ways, represent resilience and endurance in the face of patriarchal norms.

Zeliha, for instance, embodies a fierce independence that challenges societal expectations of women in Turkey. Her boldness in both her appearance and her choices, including her decision to raise Asya alone, speaks to the strength of women in patriarchal societies.

Shafak writes, “Women are like tea bags—you don’t know how strong they are until you put them in hot water.” This quote, though metaphorical, reflects the resilience of the women in the novel, particularly in how they navigate and survive societal pressures.

5. Reconciliation Through Truth

The novel emphasizes that reconciliation—whether personal or political—can only be achieved through confronting uncomfortable truths. Turkey’s unresolved history with the Armenian genocide is a central theme, but it also mirrors the personal conflicts within the Kazancı family. Just as Turkey must come to terms with its past to move forward, the characters in the novel must confront their own secrets and buried traumas.

As Shafak poignantly observes, “If you can’t make peace with your past, it will keep haunting you, shadowing your every step.” This quote highlights the importance of facing the truth, no matter how painful, to heal and move forward.

6. The Complexity of Forgiveness

Finally, The Bastard of Istanbul explores the complexity of forgiveness—both on a personal and national level. The novel suggests that forgiveness is not simple, and it cannot be rushed or forced. True reconciliation requires acknowledgment of harm and a willingness to engage with difficult truths.

In one of the novel’s most reflective passages, Shafak writes, “Forgiveness is not a gift you give to the other person. It’s something you give yourself.” This insight shifts the understanding of forgiveness from an external act to an internal process. It suggests that forgiveness is about releasing the hold that anger and resentment have over one’s life.

Conclusion

Elif Shafak’s The Bastard of Istanbul is a masterclass in storytelling, weaving together lessons on history, identity, memory, and the power of women.

Through its richly developed characters and intricate plot, the novel teaches readers that the past is never truly behind us, and that healing—whether personal or collective—requires truth, memory, and sometimes, forgiveness. The novel serves as a reminder of the power of stories in shaping both individual lives and the course of history.