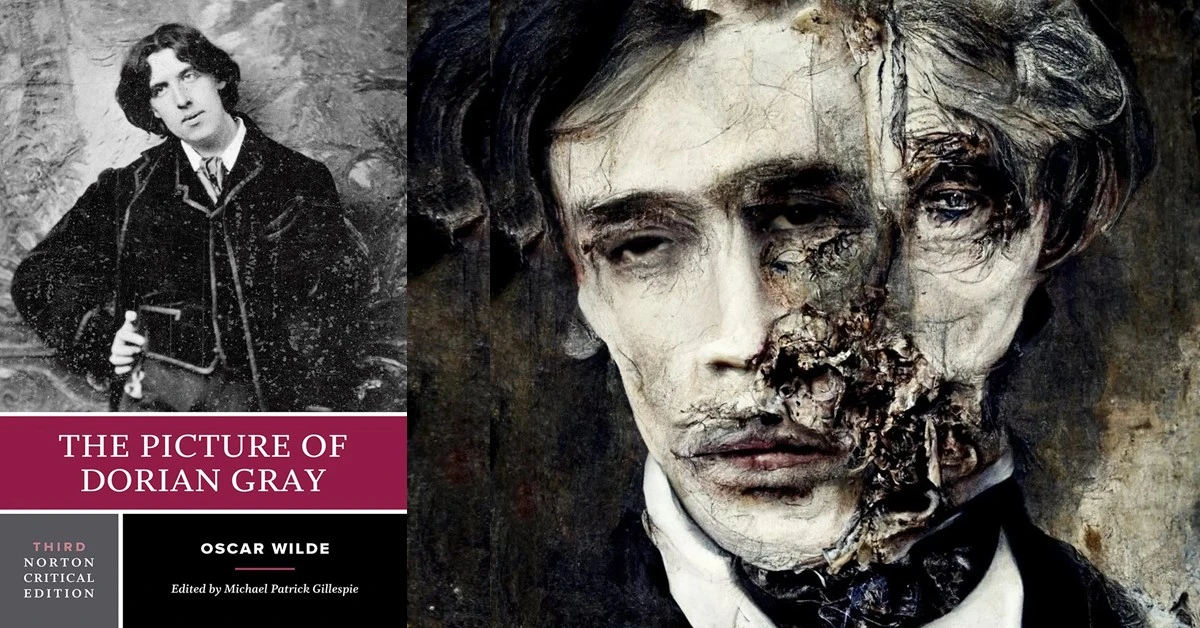

Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray is a groundbreaking exploration of vanity, moral degradation, and the perils of hedonism. Upon its publication, it faced strong backlash for its audacious depiction of amorality and its thinly veiled homoeroticism, leading to revisions and widespread controversy.

Yet, the novel has since gained critical acclaim, its once-scandalous content now celebrated as a timeless Gothic masterpiece.

Wilde’s tale, deeply philosophical and often unsettling, has inspired countless adaptations, reinforcing its enduring relevance in discussions of beauty, morality, and the human condition.

In the shadow of late Victorian society, Wilde crafts a portrait of a man seduced by the allure of eternal youth, only to uncover the harrowing cost of his soul’s disintegration. Dorian’s journey resonates not merely as a narrative of decadence but as a philosophical inquiry into the dichotomy of appearance versus essence—a motif as timeless as art itself.

Wilde, with his characteristic wit and piercing critique of societal norms, uses Dorian’s tale as a mirror to expose the hypocrisies of his age.

The Picture of Dorian Gray’s exploration of the consequences of aestheticism and the moral corruption veiled by beauty remains hauntingly relevant, challenging readers to confront the paradoxes of their own lives. Through Dorian Gray, Wilde compels us to ask: is the pursuit of perfection worth the erosion of the self?

Overview

The Picture of Dorian Gray, Wilde’s only novel, was published before he became successful as a playwright, initially in a shorter version in the July 1890 edition of the American Lippincott’s Magazine.

The magazine sold well, but critics were scathing about Wilde’s story, which they regarded as prurient and corrupt. Wilde then revised and expanded the story, and it was published in novel form by Ward, Lock, and Company in April 1891.

In the second version, Wilde included a preface of numerous aphorisms that answered his critics and laid out his aesthetic principles, such as “The artist is the creator of beautiful things” and “There is no such thing as a moral or immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.”

At the centre of The Picture of Dorian Gray is the Faust-like theme of the mortal who craves eternal youth.

The protagonist, Dorian Gray, a young man of remarkable beauty and innocence, inspires an artist admirer, Basil Hallward, to paint an extraordinarily fine portrait of him. However, the artist resolves never to exhibit the work because it reveals too obviously his adoration for his subject.

While Hallward seeks to protect the impressionable Dorian from the corruption of the world, , Lord Henry Wotton, the painter’s cynical associate, urges Dorian to indulge his natural impulses and revel in a life of hedonism, pleasure centred life.

Influenced by Wotton’s ideas, Dorian becomes envious of the likeness in the portrait, and laments that while he must grow old and lose his beauty, the figure in the painting will enjoy eternal youth. He makes a wish that the situation should be reversed, and over time the wish is granted. Dorian sinks deeper and deeper into a life of indulgence and vice, but remains perfect in outward appearance, while the painting grows ever more degraded and decrepit.

Plot

Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray is a literary exploration of morality, hedonism, and the duality of human nature, woven into a rich narrative that has captivated readers for over a century. At its heart lies a Faustian tale of a man who exchanges the purity of his soul for eternal youth and beauty, a transaction that becomes both his greatest triumph and his most damning curse.

The story begins in the opulent studio of Basil Hallward, a devoted artist who becomes enamored with the beauty of a young aristocrat, Dorian Gray. Basil’s adoration for Dorian is almost reverent; he describes him as a being who embodies an ideal of art itself. “The only excuse for making a useless thing is that one admires it intensely,” says Lord Henry Wotton, a mutual acquaintance, foreshadowing the complex interplay of beauty and morality that follows.

Lord Henry, a charismatic and cynical hedonist, quickly exerts a profound influence over Dorian. During their first meeting, he expounds on his philosophy of life: “The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it.”

This credo strikes a chord with the impressionable Dorian, who begins to view life as a pursuit of pleasure and aesthetic experience. When Basil completes a stunning portrait of Dorian, capturing his youthful perfection, Dorian, influenced by Lord Henry’s provocative words, laments the inevitability of his own aging. He makes a desperate wish: that the portrait would bear the marks of time and sin, leaving his own body untouched by the ravages of life.

Unbeknownst to him, this wish is mysteriously granted.

The portrait becomes a reflection of Dorian’s soul, changing to reveal the consequences of his actions while his outward appearance remains pristine. This uncanny phenomenon sets the stage for Dorian’s moral descent. Initially, his sins are minor, but emboldened by his apparent immunity to consequence, he spirals into a life of debauchery and cruelty.

Dorian’s first significant moral failure comes with his treatment of Sibyl Vane, a young actress he claims to love. Captivated by her performances, he declares her to be an incarnation of Shakespearean heroines. However, when she abandons her art, overwhelmed by her love for him, her performance falters. Dorian’s reaction is devastating: “You have killed my love,” he tells her coldly, rejecting her with a callousness that leads to her suicide.

That night, Dorian notices a subtle change in his portrait: a cruel line around the mouth. This marks the beginning of his awareness that the painting serves as a ledger of his sins.

Over the years, Dorian indulges in every vice imaginable, his reputation tarnished even as his visage remains angelic. Wilde’s prose evokes a sense of both allure and horror as Dorian explores opium dens and corrupts those around him. “There is no such thing as a good influence,” Lord Henry tells him early on, and Dorian becomes a living evidence to this assertion, bringing ruin to those who enter his orbit.

One of the most chilling moments occurs when Basil confronts Dorian about the rumors surrounding his life. Basil’s genuine concern for Dorian’s soul leads him to implore: “Pray, Dorian, pray.” In response, Dorian shows Basil the portrait, now grotesque and unrecognizable. Basil is horrified, exclaiming, “You have done enough evil in your life.”

Overcome by a mix of shame and rage, Dorian murders Basil in cold blood, solidifying his descent into irredeemable darkness.

Haunted by his crime, Dorian seeks solace in further indulgence but finds no escape from the torment of his conscience. Wilde’s depiction of Dorian’s psychological unraveling is masterful, as he becomes increasingly paranoid and fixated on the portrait. He begins to despise it, seeing it as a “visible symbol of the degradation of sin,” and yet he cannot part from it, for it is the repository of his true self.

In a final act of desperation, Dorian decides to destroy the portrait, believing it will free him from his guilt.

Armed with a knife, he slashes the canvas. A scream is heard, and when his servants enter the locked room, they find the portrait restored to its original beauty, while Dorian lies dead on the floor, aged and withered beyond recognition. In this climactic moment, Wilde underscores the inescapable truth that no one can evade the consequences of their actions forever.

Wilde’s novel is rich with themes and symbols that invite endless interpretation. The portrait itself is a powerful metaphor for the duality of human nature, serving as both a mirror and a mask. It reflects not only Dorian’s sins but also the societal hypocrisy that allows him to maintain his façade of respectability.

Lord Henry’s epigrams, though witty and seductive, reveal the dangers of a philosophy divorced from morality. Basil’s tragic fate serves as a poignant reminder of the vulnerability of those who seek to create beauty in a world that often destroys it.

Perhaps the most enduring aspect of The Picture of Dorian Gray is its exploration of the soul.

Dorian’s journey is a cautionary tale about the perils of valuing surface over substance, of sacrificing one’s humanity for the fleeting pleasures of the senses. “The soul is a terrible reality. It can be bought, and sold, and bartered away,” Dorian admits in a rare moment of introspection. In the end, his soul is both his greatest torment and his ultimate undoing.

In reflecting on Wilde’s masterpiece, one cannot help but consider the ways in which it continues to resonate with contemporary readers.

Its themes of vanity, moral corruption, and the pursuit of pleasure are as relevant today as they were in the late 19th century. The novel’s haunting conclusion lingers long after the final page, a testament to Wilde’s genius in crafting a story that speaks to the darkest corners of the human heart.

Setting

The Picture of Dorian Gray is set predominantly in 1890s London, with an interlude at Dorian’s country estate of Selby Royal.

Two sides of Victorian London are depicted, the opulent West End inhabited by the upper classes, and the shadowy underworld of the East End with its docks, public houses, and opium dens.

At first, Dorian is excited by the nefarious possibilities of London, “I determined to go out in search of some adventure. I felt that this grey monstrous London of ours, with its myriads of people, its sordid sinners, and its splendid sins…must have something in store for me.” Later, after he has murdered Basil Hallward, seeking distraction he takes a cab to the East End where “There were opium dens where one could buy oblivion, dens of horror where the memory of old sins could be destroyed by the madness of sins that were new.”

Themes And Characters

Dorian Gray starts out as an Adonis-like figure who embodies the ideals of youth and beauty, so much so that the painter Basil Hallward becomes infatuated with him.

Dorian’s vanity is easily exploited by Sir Henry Wotton, who persuades the youth that his time is limited and he will soon be helpless to stop the process of ageing and physical decline. To truly thrive, Dorian must live a life of sensation as the “visible symbol” of a “new Hedonism”.

As Dorian embraces his new life of self-indulgence, the portrait of him painted by Hallward takes on a supernatural role, acting as a witness to his moral decline. When Dorian impulsively falls in love with the actress Sibyl Vane, but then callously discards her driving her to suicide, the painting begins to show the first signs of deterioration, while Dorian, getting what he wished for, remains unscathed. The painting grows more and more repugnant as Dorian satisfies his twin appetites for aesthetic pleasure and criminality, culminating in the murder of Basil Hallward.

The picture becomes Dorian’s conscience—“It had been like conscience to him. Yes, it had been conscience.”—and in the attempt to release himself from its clutches he destroys it. In so doing, he destroys himself.

Essentially The Picture of Dorian Gray is a moral debate between the characters of Basil Hallward and Sir Henry Wotton. Hallward believes in a moral universe in which God sees into men’s souls, rewarding virtue and punishing sin. He believes that “if one lives merely for one’s self…one pays a terrible price for doing so” in “remorse, in suffering, in…the consciousness of degradation”. “You have a wonderful influence. Let it be for good, not for evil,” he urges Dorian, and he is horrified by the stories he hears of Dorian’s depravity, “My God! Don’t tell me that you are bad, and corrupt, and shameful.”

Yet, at the end, the moral certainties invoked by Basil are proven to be unfounded. The representatives of innocence and virtue suffer—Sibyl Vane dies in tragic circumstances; her brother James perishes in a shooting accident; Hallward himself is brutally murdered by Dorian; Alan Campbell, a friend whom Dorian blackmails into disposing of Hallward’s body, is driven to suicide.

Only the amoral Sir Henry Wotton survives, and it could be argued that Dorian himself escapes punishment as he is never called to account for his crimes.

Wotton’s beliefs stand in opposition to those of Basil Hallward, and it is his influence that awakens Dorian to the pleasures of the self. Indeed, influence is one of the persistent themes of the novel, and Wilde uses the word repeatedly throughout. Wotton first tells Dorian that “all influence is immoral”, but privately reflects that there is “something terribly enthralling in the exercise of influence”. It is Wotton who introduces Dorian to the yellow book, a French novel (partly inspired by Joris Karl Huysmans’s À rebours), which influences him so much that it becomes the malign blueprint for his decadent adventures.

Wotton’s is essentially a cynical view of existence. Humanity is faced with a hostile universe, which is random and cruel, and so the only worthwhile response is to indulge in selfish pleasure.

The alternative is a life of cowardice and conformity to the twin “terrors” of society and religion. Wotton even comes up with his own creed, new Hedonism. The ultimate goal in life is self-fulfilment and to suppress this natural urge is to negate life itself: “Every impulse that we strive to strangle broods in the mind, and poisons us.” But Wotton is not a practising hedonist. He takes the role of the spectator, opting out of an active life himself so that he can study it coolly in others.

He is a great wit, but he avoids life, hiding behind witticisms because he cannot stand pain: “I can sympathize with everything except suffering…I cannot sympathize with that. It is too ugly, too horrible, too distressing.” For all his observations about life, Wotton is far from the perceptive judge of character that he thinks he is.

Even after all Dorian’s excesses, he still believes him to be incapable of murder: “It is not in you, Dorian, to commit a murder. I am sorry if I hurt your vanity by saying so, but I assure you it is true.”

To a limited extent, the story can be read as a morality tale, with all three of the main characters suffering some kind of comeuppance for their failings: Dorian for attempting to snuff out conscience; Hallward for being too admiring of physical beauty; and Wotton, who cuts a lonely figure by the end, for opting out of life itself. However, this presents something of a paradox.

Wilde was against didacticism in art. He held the opposing view to the prevailing opinion in Victorian times that the object of art should be moral improvement. Wilde believed that art’s purpose was to be just that: art, the creation of beautiful things; he thought that ethics were inimical to creativity and he said as much in the preface: “No artist has ethical sympathies. An ethical sympathy in an artist is an unpardonable mannerism of style.” Wilde himself addressed the paradox, arguing that the moral elements of the story were “deliberately suppressed” so that they became “simply a dramatic element” in The Picture of Dorian Gray.

The real meaning of the work was too multifarious to be reduced merely to a moral message, and his flippant remarks in a letter to a friend might well serve as a wry comment on such reductive interpretations: “Basil Hallward is what I think I am: Lord Henry what the world thinks me: Dorian what I would like to be.”

Ultimately, the impulses embodied in the character of Dorian Gray, and argued over by Hallward and Wotton, are not simply a question of good versus evil.

More subtly, they point to the challenges of the human condition: the struggle to reconcile the conflicting demands of instinct and intellect, of desire and conscience.

Core Lessons from The Picture of Dorian Gray

1. The Allure and Danger of Aestheticism

Oscar Wilde opens The Picture of Dorian Gray with a preface that champions art for art’s sake, proclaiming, “All art is quite useless”—a provocative statement emphasizing art’s independence from moral or utilitarian purposes.

However, as the narrative unfolds, Wilde reveals the peril of aestheticism when misapplied. Dorian Gray’s obsessive pursuit of beauty and pleasure leads him to a life devoid of empathy and responsibility. Lord Henry Wotton’s philosophy encapsulates this, asserting, “The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it”. This hedonistic mantra becomes Dorian’s guiding principle, driving him to make decisions that prioritize personal gratification at the expense of others.

Dorian’s ultimate downfall underscores a critical lesson: beauty and pleasure, when worshipped as ends in themselves, can distort one’s sense of morality.

The transformation of his portrait—bearing the physical consequences of his sins while he remains outwardly youthful—symbolizes the grotesque cost of unchecked indulgence.

2. The Corruption of the Soul

Central to The Picture of Dorian Gray is the Faustian bargain, a pact whereby a person trades something of supreme moral or spiritual importance, such as personal values or the soul, Dorian makes, trading his soul for eternal youth and beauty.

This exchange serves as a cautionary tale about the fragility of the human soul when subjected to vanity and vice. Wilde writes, “The soul is a terrible reality. It can be bought, and sold, and bartered away. It can be poisoned, or made perfect. There is a soul in each one of us. I know it”. Dorian’s descent into moral depravity—culminating in murder and the betrayal of those who love him—highlights how neglecting one’s conscience leads to self-destruction.

The haunting description of Dorian observing his corrupted portrait reveals The Picture of Dorian Gray’s moral heart.

Wilde writes, “He grew more and more enamoured of his own beauty, more and more interested in the corruption of his own soul”. This chilling depiction reminds readers of the importance of introspection and integrity in maintaining one’s humanity.

3. The Double Life: Appearance vs. Reality

Dorian’s life illustrates the danger of living a double existence. To society, he remains the epitome of charm and innocence, while his secret sins accumulate in the portrait hidden away in his attic. This duality mirrors Wilde’s critique of Victorian society’s obsession with appearances and its tendency to ignore underlying moral decay.

In Chapter 15, Wilde writes, “Dorian felt keenly the terrible pleasure of a double life.” This line encapsulates the psychological toll of duplicity and the human desire to reconcile one’s outward image with inner truths.

Ultimately, Dorian’s inability to face his portrait—his true self—leads to his undoing. The lesson here is clear: authenticity and self-acceptance are vital to living a meaningful life.

4. The Role of Influence and Personal Responsibility

Lord Henry’s influence on Dorian is profound, yet Wilde does not absolve Dorian of responsibility for his choices. In Chapter 8, Lord Henry remarks, “There is no such thing as a good influence, Mr. Gray. All influence is immoral.” While this statement reflects Henry’s philosophy, it also underscores the dangers of surrendering one’s agency to external forces.

Dorian’s tragedy lies in his failure to assert his moral autonomy. Instead, he adopts Lord Henry’s cynical worldview and allows it to dictate his actions.

The Picture of Dorian Gray warns readers against the passive absorption of ideas and emphasizes the importance of critical thinking and self-awareness in shaping one’s destiny.

Both The Picture of Dorian Gray and Sam Mendes’s American Beauty explore themes of beauty, desire, and the existential emptiness of modern life. While Wilde’s novel focuses on the Victorian era’s moral and aesthetic anxieties, American Beauty critiques contemporary suburban culture and the quest for superficial perfection.

About The Author

Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde was born in Dublin, Ireland, on October 16, 1854. His father was Sir William Wilde, a leading surgeon, and his mother Lady Jane Wilde a renowned poet and Irish nationalist.

After attending school in County Fermanagh, Wilde studied Classics at Trinity College, Dublin, and Magdalen College, Oxford, where his flamboyance and wit brought him celebrity. He was also a brilliant student, graduating from Oxford with a double first and winning the 1878 Newdigate Prize for his poem “Ravenna”.

After Oxford, he established himself as a member of London society, and championed aestheticism, a philosophy that advocated art for art’s sake.

Although his early writing attempts were poorly received, such was the brilliance of his personality that he enjoyed great success in the United States and Canada as a public speaker. On his return to London, in 1884 he married Constance Lloyd, the daughter of a Dublin barrister, with whom he subsequently had two children, Cyril and Vyvyan. From 1887 to 1889 he edited the magazine The Woman’s World, while also forging a career as a writer.

The following decade he enjoyed popular and critical acclaim in the theatre with a string of comic plays Lady Windermere’s Fan (1892), A Woman of No Importance (1893), An Ideal Husband (1895), and The Importance of Being Earnest (1895).

In 1895 Wilde sued Queensberry for libel but lost when evidence came to light of his associations with male prostitutes.

As a result, Wilde was tried and convicted of gross indecency, and sentenced to two years’ hard labour in Reading gaol. His reputation, finances, and health were ruined by the scandal, and three years after his release he died of cerebral meningitis in Paris on November 30, 1900.

Reception

When The Picture of Dorian Gray was first published in 1890, it sparked significant controversy, especially in Victorian England, due to its perceived immorality and homoerotic undertones.

The public and critics alike expressed concern over The Picture of Dorian Gray‘s message of hedonism and the character Dorian’s indulgence in vice without immediate consequence. Reviewers condemned The Picture of Dorian Gray with The Daily Chronicle calling it a work that would “taint every young mind” and others labeling it “unclean” and “effeminate.”

Despite this, Wilde defended his work passionately, claiming it was a reflection of art for art’s sake, a concept prevalent in aestheticism. Over time, the novel grew in stature, becoming a Gothic and philosophical literary classic that continues to provoke thought and discussion on morality, vanity, and the consequences of self-indulgence.

Excerpt from The Picture of Dorian Gray

The Preface

The artist is the creator of beautiful things.

To reveal art and conceal the artist is art’s aim.

The critic is he who can translate into another manner or a new material his impression of beautiful things.

The highest as the lowest form of criticism is a mode of autobiography.

Those who find ugly meanings in beautiful things are corrupt without being charming. This is a fault.

Those who find beautiful meanings in beautiful things are the cultivated. For these there is hope.

They are the elect to whom beautiful things mean only Beauty.

There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.

The nineteenth century dislike of Realism is the rage of Caliban seeing his own face in a glass.

The nineteenth century dislike of Romanticism is the rage of Caliban not seeing his own face in a glass.

The moral life of man forms part of the subject-matter of the artist, but the morality of art consists in the perfect use of an imperfect medium.

No artist desires to prove anything. Even things that are true can be proved.

No artist has ethical sympathies. An ethical sympathy in an artist is an unpardonable mannerism of style.

No artist is ever morbid. The artist can express everything.

Thought and language are to the artist instruments of an art.

Vice and virtue are to the artist materials for an art.

From the point of view of form, the type of all the arts is the art of the musician. From the point of view of feeling, the actor’s craft is the type.

All art is at once surface and symbol.

Those who go beneath the surface do so at their peril.

Those who read the symbol do so at their peril.

It is the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors.

Diversity of opinion about a work of art shows that the work is new, complex, and vital.

When critics disagree the artist is in accord with himself.

We can forgive a man for making a useful thing as long as he does not admire it. The only excuse for making a useless thing is that one admires it intensely.

All art is quite useless.

Chapter Two

As they entered they saw Dorian Gray. He was seated at the piano, with his back to them, turning over the pages of a volume of Schumann’s “Forest Scenes.” “You must lend me these, Basil,” he cried. “I want to learn them. They are perfectly charming.”

“That entirely depends on how you sit to-day, Dorian.”

“Oh, I am tired of sitting, and I don’t want a life-sized portrait of myself,” answered the lad, swinging round on the music-stool, in a wilful, petulant manner. When he caught sight of Lord Henry, a faint blush coloured his cheeks for a moment, and he started up. “I beg your pardon, Basil, but I didn’t know you had any one with you.”

“This is Lord Henry Wotton, Dorian, an old Oxford friend of mine. I have just been telling him what a capital sitter you were, and now you have spoiled everything.”

“You have not spoiled my pleasure in meeting you, Mr. Gray,” said Lord Henry, stepping forward and extending his hand. “My aunt has often spoken to me about you. You are one of her favourites, and, I am afraid, one of her victims also.”

“I am in Lady Agatha’s black books at present,” answered Dorian, with a funny look of penitence. “I promised to go to a club in Whitechapel with her last Tuesday, and I really forgot all about it. We were to have played a duet together—three duets, I believe. I don’t know what she will say to me. I am far too frightened to call.”

“Oh, I will make your peace with my aunt. She is quite devoted to you. And I don’t think it really matters about your not being there. The audience probably thought it was a duet. When Aunt Agatha sits down to the piano she makes quite enough noise for two people.”

“That is very horrid to her, and not very nice to me,” answered Dorian, laughing.

Lord Henry looked at him. Yes, he was certainly wonderfully handsome, with his finely-curved scarlet lips, his frank blue eyes, his crisp gold hair. There was something in his face that made one trust him at once. All the candour of youth was there, as well as all youth’s passionate purity. One felt that he had kept himself unspotted from the world. No wonder Basil Hallward worshipped him.

“You are too charming to go in for philanthropy, Mr. Gray—far too charming.” And Lord Henry flung himself down on the divan, and opened his cigarette-case.

The painter had been busy mixing his colours and getting his brushes ready. He was looking worried, and when he heard Lord Henry’s last remark he glanced at him, hesitated for a moment, and then said, “Harry, I want to finish this picture to-day. Would you think it awfully rude of me if I asked you to go away?”

Lord Henry smiled, and looked at Dorian Gray. “Am I to go, Mr. Gray?” he asked.

“Oh, please don’t, Lord Henry. I see that Basil is in one of his sulky moods; and I can’t bear him when he sulks. Besides, I want you to tell me why I should not go in for philanthropy.”

“I don’t know that I shall tell you that, Mr. Gray. It is so tedious a subject that one would have to talk seriously about it. But I certainly shall not run away, now that you have asked me to stop. You don’t really mind, Basil, do you? You have often told me that you liked your sitters to have some one to chat to.”

Hallward bit his lip. “If Dorian wishes it, of course you must stay. Dorian’s whims are laws to everybody, except himself.”

Lord Henry took up his hat and gloves. “You are very pressing, Basil, but I am afraid I must go. I have promised to meet a man at the Orleans. Good-bye, Mr. Gray. Come and see me some afternoon in Curzon Street. I am nearly always at home at five o’clock. Write to me when you are coming. I should be sorry to miss you.”

“Basil,” cried Dorian Gray, “if Lord Henry Wotton goes I shall go too. You never open your lips while you are painting, and it is horribly dull standing on a platform and trying to look pleasant. Ask him to stay. I insist upon it.”

“Stay, Harry, to oblige Dorian, and to oblige me,” said Hallward, gazing intently at his picture. “It is quite true, I never talk when I am working, and never listen either, and it must be dreadfully tedious for my unfortunate sitters. I beg you to stay.”

“But what about my man at the Orleans?”

The painter laughed. “I don’t think there will be any difficulty about that. Sit down again, Harry. And now, Dorian, get up on the platform, and don’t move about too much, or pay any attention to what Lord Henry says. He has a very bad influence over all his friends, with the single exception of myself.”

Dorian Gray stepped up on the dais, with the air of a young Greek martyr, and made a little moue of discontent to Lord Henry, to whom he had rather taken a fancy. He was so unlike Basil. They made a delightful contrast. And he had such a beautiful voice. After a few moments he said to him, “Have you really a very bad influence, Lord Henry? As bad as Basil says?”

“There is no such thing as a good influence, Mr. Gray. All influence is immoral—immoral from the scientific point of view.”

“Why?”

“Because to influence a person is to give him one’s own soul. He does not think his natural thoughts, or burn with his natural passions. His virtues are not real to him. His sins, if there are such things as sins, are borrowed. He becomes an echo of some one else’s music, an actor of a part that has not been written for him. The aim of life is self-development. To realize one’s nature perfectly—that is what each of us is here for. People are afraid of themselves, nowadays.

They have forgotten the highest of all duties, the duty that one owes to one’s self. Of course they are charitable. They feed the hungry, and clothe the beggar. But their own souls starve, and are naked.

Courage has gone out of our race. Perhaps we never really had it. The terror of society, which is the basis of morals, the terror of God, which is the secret of religion—these are the two things that govern us. And yet—”

“Just turn your head a little more to the right, Dorian, like a good boy,” said the painter, deep in his work, and conscious only that a look had come into the lad’s face that he had never seen there before.

“And yet,” continued Lord Henry, in his low, musical voice, and with that graceful wave of the hand that was always so characteristic of him, and that he had even in his Eton days, “I believe that if one man were to live out his life fully and completely, were to give form to every feeling, expression to every thought, reality to every dream—I believe that the world would gain such a fresh impulse of joy that we would forget all the maladies of medievalism, and return to the Hellenic ideal—to something finer, richer, than the Hellenic ideal, it may be.

But the bravest man amongst us is afraid of himself. The mutilation of the savage has its tragic survival in the self-denial that mars our lives. We are punished for our refusals. Every impulse that we strive to strangle broods in the mind, and poisons us.

The body sins once, and has done with its sin, for action is a mode of purification. Nothing remains then but the recollection of a pleasure, or the luxury of a regret. The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it. Resist it, and your soul grows sick with longing for the things it has forbidden to itself, with desire for what its monstrous laws have made monstrous and unlawful. It has been said that the great events of the world take place in the brain. It is in the brain, and the brain only, that the great sins of the world take place also.

You, Mr. Gray, you yourself, with your rose-red youth and your rose-white boyhood, you have had passions that have made you afraid, thoughts that have filled you with terror, day-dreams and sleeping dreams whose mere memory might stain your cheek with shame—”

“Stop!” faltered Dorian Gray, “stop! you bewilder me. I don’t know what to say. There is some answer to you, but I cannot find it. Don’t speak. Let me think. Or, rather, let me try not to think.”

For nearly ten minutes he stood there, motionless, with parted lips, and eyes strangely bright. He was dimly conscious that entirely fresh influences were at work within him. Yet they seemed to him to have come really from himself. The few words that Basil’s friend had said to him—words spoken by chance, no doubt, and with wilful paradox in them—had touched some secret chord that had never been touched before, but that he felt was now vibrating and throbbing to curious pulses.

Music had stirred him like that. Music had troubled him many times. But music was not articulate. It was not a new world, but rather another chaos, that it created in us. Words! Mere words! How terrible they were! How clear, and vivid, and cruel! One could not escape from them. And yet what a subtle magic there was in them! They seemed to be able to give a plastic form to formless things, and to have a music of their own as sweet as that of viol or of lute. Mere words! Was there anything so real as words?

Yes; there had been things in his boyhood that he had not understood. He understood them now. Life suddenly became fiery-coloured to him. It seemed to him that he had been walking in fire. Why had he not known it?

With his subtle smile, Lord Henry watched him. He knew the precise psychological moment when to say nothing. He felt intensely interested. He was amazed at the sudden impression that his words had produced, and, remembering a book that he had read when he was sixteen, a book which had revealed to him much that he had not known before, he wondered whether Dorian Gray was passing through a similar experience. He had merely shot an arrow into the air. Had it hit the mark? How fascinating the lad was!

Hallward painted away with that marvellous bold touch of his, that had the true refinement and perfect delicacy that in art, at any rate comes only from strength. He was unconscious of the silence.

“Basil, I am tired of standing,” cried Dorian Gray, suddenly. “I must go out and sit in the garden. The air is stifling here.”

“My dear fellow, I am so sorry. When I am painting, I can’t think of anything else. But you never sat better. You were perfectly still. And I have caught the effect I wanted—the half-parted lips, and the bright look in the eyes. I don’t know what Harry has been saying to you, but he has certainly made you have the most wonderful expression. I suppose he has been paying you compliments. You mustn’t believe a word that he says.”

“He has certainly not been paying me compliments. Perhaps that is the reason that I don’t believe anything he has told me.”

“You know you believe it all,” said Lord Henry, looking at him with his dreamy, languorous eyes. “I will go out to the garden with you. It is horribly hot in the studio. Basil, let us have something iced to drink, something with strawberries in it.”

“Certainly, Harry. Just touch the bell, and when Parker comes I will tell him what you want. I have got to work up this background, so I will join you later on. Don’t keep Dorian too long. I have never been in better form for painting than I am to-day. This is going to be my masterpiece. It is my masterpiece as it stands.”

Lord Henry went out to the garden, and found Dorian Gray burying his face in the great cool lilac-blossoms, feverishly drinking in their perfume as if it had been wine. He came close to him, and put his hand upon his shoulder. “You are quite right to do that,” he murmured. “Nothing can cure the soul but the senses, just as nothing can cure the senses but the soul.”

The lad started and drew back. He was bare-headed, and the leaves had tossed his rebellious curls and tangled all their gilded threads. There was a look of fear in his eyes, such as people have when they are suddenly awakened. His finely-chiselled nostrils quivered, and some hidden nerve shook the scarlet of his lips and left them trembling.

“Yes,” continued Lord Henry, “that is one of the great secrets of life—to cure the soul by means of the senses, and the senses by means of the soul. You are a wonderful creation. You know more than you think you know, just as you know less than you want to know.”

Dorian Gray frowned and turned his head away. He could not help liking the tall, graceful young man who was standing by him. His romantic olive-coloured face and worn expression interested him. There was something in his low, languid voice that was absolutely fascinating. His cool, white, flower-like hands, even, had a curious charm. They moved, as he spoke, like music, and seemed to have a language of their own. But he felt afraid of him, and ashamed of being afraid. Why had it been left for a stranger to reveal him to himself?

He had known Basil Hallward for months, but the friendship between them had never altered him. Suddenly there had come some one across his life who seemed to have disclosed to him life’s mystery. And, yet, what was there to be afraid of? He was not a schoolboy or a girl. It was absurd to be frightened.

“Let us go and sit in the shade,” said Lord Henry. “Parker has brought out the drinks, and if you stay any longer in this glare you will be quite spoiled, and Basil will never paint you again. You really must not allow yourself to become sunburnt. It would be unbecoming.”

“What can it matter?” cried Dorian Gray, laughing, as he sat down on the seat at the end of the garden.

“It should matter everything to you, Mr. Gray.”

“Why?

“Because you have the most marvellous youth, and youth is the one thing worth having.”

“I don’t feel that, Lord Henry.”

“No, you don’t feel it now. Some day, when you are old and wrinkled and ugly, when thought has seared your forehead with its lines, and passion branded your lips with its hideous fires, you will feel it, you will feel it terribly. Now, wherever you go, you charm the world. Will it always be so?… You have a wonderfully beautiful face, Mr. Gray. Don’t frown. You have. And Beauty is a form of Genius—is higher, indeed, than Genius as it needs no explanation.

It is of the great facts of the world, like sunlight, or spring-time, or the reflection in dark waters of that silver shell we call the moon. It cannot be questioned. It has its divine right of sovereignty. It makes princes of those who have it. You smile? Ah! when you have lost it you won’t smile… People say sometimes that Beauty is only superficial. That may be so. But at least it is not so superficial as Thought is. To me, Beauty is the wonder of wonders.

It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances. The true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible… Yes, Mr. Gray, the gods have been good to you. But what the gods give they quickly take away. You have only a few years in which to live really, perfectly, and fully. When your youth goes, your beauty will go with it, and then you will suddenly discover that there are no triumphs left for you, or have to content yourself with those mean triumphs that the memory of your past will make more bitter than defeats. Every month as it wanes brings you nearer to something dreadful. Time is jealous of you, and wars against your lilies and your roses. You will become sallow, and hollow-cheeked, and dull-eyed. You will suffer horribly… Ah! realize your youth while you have it.

Don’t squander the gold of your days, listening to the tedious, trying to improve the hopeless failure, or giving away your life to the ignorant, the common, and the vulgar. These are the sickly aims, the false ideals, of our age. Live! Live the wonderful life that is in you! Let nothing be lost upon you. Be always searching for new sensations. Be afraid of nothing… A new Hedonism—that is what our century wants. You might be its visible symbol. With your personality there is nothing you could not do. The world belongs to you for a season… The moment I met you I saw that you were quite unconscious of what you really are, of what you really might be.

There was so much in you that charmed me that I felt I must tell you something about yourself. I thought how tragic it would be if you were wasted. For there is such a little time that your youth will last— such a little time. The common hill-flowers wither, but they blossom again. The laburnum will be as yellow next June as it is now. In a month there will be purple stars on the clematis, and year after year the green night of its leaves will hold its purple stars. But we never get back our youth. The pulse of joy that beats in us at twenty, becomes sluggish. Our limbs fail, our senses rot.

We degenerate into hideous puppets, haunted by the memory of the passions of which we were too much afraid, and the exquisite temptations that we had not the courage to yield to. Youth! Youth! There is absolutely nothing in the world but youth!”

Dorian Gray listened, open-eyed and wondering. The spray of lilac fell from his hand upon the gravel. A furry bee came and buzzed round it for a moment. Then it began to scramble all over the oval stellated globe of the tiny blossoms.

He watched it with that strange interest in trivial things that we try to develop when things of high import make us afraid, or when we are stirred by some new emotion for which we cannot find expression, or when some thought that terrifies us lays sudden siege to the brain and calls on us to yield. After a time the bee flew away. He saw it creeping into the stained trumpet of a Tyrian convolvulus. The flower seemed to quiver, and then swayed gently to and fro.

Suddenly the painter appeared at the door of the studio, and made staccato signs for them to come in. They turned to each other, and smiled.

“I am waiting,” he cried. “Do come in. The light is quite perfect, and you can bring your drinks.”

They rose up, and sauntered down the walk together. Two green-and-white butterflies fluttered past them, and in the pear-tree at the corner of the garden a thrush began to sing.

“You are glad you have met me, Mr. Gray,” said Lord Henry, looking at him.

“Yes, I am glad now. I wonder shall I always be glad?”

“Always! That is a dreadful word. It makes me shudder when I hear it. Women are so fond of using it. They spoil every romance by trying to make it last for ever. It is a meaningless word, too. The only difference between a caprice and a life-long passion is that the caprice lasts a little longer.”

As they entered the studio, Dorian Gray put his hand upon Lord Henry’s arm. “In that case, let our friendship be a caprice,” he murmured, flushing at his own boldness, then stepped up on the platform and resumed his pose.

Lord Henry flung himself into a large wicker arm-chair, and watched him. The sweep and dash of the brush on the canvas made the only sound that broke the stillness, except when, now and then, Hallward stepped back to look at his work from a distance. In the slanting beams that streamed through the open doorway the dust danced and was golden. The heavy scent of the roses seemed to brood over everything.

After about a quarter of an hour Hallward stopped painting, looked for a long time at Dorian Gray, and then for a long time at the picture, biting the end of one of his huge brushes, and frowning. “It is quite finished,” he cried at last, and stooping down he wrote his name in long vermilion letters on the left-hand corner of the canvas.

Lord Henry came over and examined the picture. It was certainly a wonderful work of art, and a wonderful likeness as well.

“My dear fellow, I congratulate you most warmly,” he said. “It is the finest portrait of modern times. Mr. Gray, come over and look at yourself.”

The lad started, as if awakened from some dream. “Is it really finished?” he murmured, stepping down from the platform.

“Quite finished,” said the painter. “And you have sat splendidly today. I am awfully obliged to you.”

“That is entirely due to me,” broke in Lord Henry. “Isn’t it, Mr. Gray?”

Dorian made no answer, but passed listlessly in front of his picture and turned towards it. When he saw it he drew back, and his cheeks flushed for a moment with pleasure. A look of joy came into his eyes, as if he had recognized himself for the first time. He stood there motionless and in wonder, dimly conscious that Hallward was speaking to him, but not catching the meaning of his words. The sense of his own beauty came on him like a revelation.

He had never felt it before. Basil Hallward’s compliments had seemed to him to be merely the charming exaggerations of friendship. He had listened to them, laughed at them, forgotten them. They had not influenced his nature. Then had come Lord Henry Wotton with his strange panegyric on youth, his terrible warning of its brevity. That had stirred him at the time, and now, as he stood gazing at the shadow of his own loveliness, the full reality of the description flashed across him.

Yes, there would be a day when his face would be wrinkled and wizen, his eyes dim and colourless, the grace of his figure broken and deformed. The scarlet would pass away from his lips, and the gold steal from his hair. The life that was to make his soul would mar his body. He would become dreadful, hideous, and uncouth.

As he thought of it, a sharp pang of pain struck through him like a knife, and made each delicate fibre of his nature quiver. His eyes deepened into amethyst, and across them came a mist of tears. He felt as if a hand of ice had been laid upon his heart.

“Don’t you like it?” cried Hallward at last, stung a little by the lad’s silence, not understanding what it meant.

“Of course he likes it,” said Lord Henry. “Who wouldn’t like it? It is one of the greatest things in modern art. I will give you anything you like to ask for it. I must have it.”

“It is not my property, Harry.”

“Whose property is it?”

“Dorian’s, of course,” answered the painter.

“He is a very lucky fellow.”

“How sad it is!” murmured Dorian Gray, with his eyes still fixed upon his own portrait. “How sad it is! I shall grow old, and horrible, and dreadful. But this picture will remain always young. It will never be older than this particular day of June… If it were only the other way! If it were I who was to be always young, and the picture that was to grow old! For that—for that—I would give everything! Yes, there is nothing in the whole world I would not give! I would give my soul for that!”

“You would hardly care for such an arrangement, Basil,” cried Lord Henry, laughing. “It would be rather hard lines on your work.”

“I should object very strongly, Harry,” said Hallward.

Dorian Gray turned and looked at him. “I believe you would, Basil. You like your art better than your friends. I am no more to you than a green bronze figure. Hardly as much, I dare say.”

The painter stared in amazement. It was so unlike Dorian to speak like that. What had happened? He seemed quite angry. His face was flushed and his cheeks burning.

“Yes,” he continued, “I am less to you than your ivory Hermes or your silver Faun. You will like them always. How long will you like me? Till I have my first wrinkle, I suppose. I know, now, that when one loses one’s good looks, whatever they may be, one loses everything. Your picture has taught me that. Lord Henry Wotton is perfectly right. Youth is the only thing worth having. When I find that I am growing old, I shall kill myself.

Hallward turned pale, and caught his hand. “Dorian! Dorian!” he cried, “don’t talk like that. I have never had such a friend as you, and I shall never have such another. You are not jealous of material things, are you?—you who are finer than any of them!”

“I am jealous of everything whose beauty does not die. I am jealous of the portrait you have painted of me. Why should it keep what I must lose? Every moment that passes takes something from me, and gives something to it. Oh, if it were only the other way! If the picture could change, and I could be always what I am now! Why did you paint it? It will mock me some day—mock me horribly!” The hot tears welled into his eyes; he tore his hand away, and, flinging himself on the divan, he buried his face in the cushions, as though he was praying.

“This is your doing, Harry,” said the painter, bitterly.

Lord Henry shrugged his shoulders. “It is the real Dorian Gray—that is all.”

“It is not.”

“If it is not, what have I to do with it?”

“You should have gone away when I asked you,” he muttered.

“I stayed when you asked me,” was Lord Henry’s answer.

“Harry, I can’t quarrel with my two best friends at once, but between you both you have made me hate the finest piece of work I have ever done, and I will destroy it. What is it but canvas and colour? I will not let it come across our three lives and mar them.”

Dorian Gray lifted his golden head from the pillow, and with pallid face and tear-stained eyes looked at him, as he walked over to the deal painting-table that was set beneath the high curtained window. What was he doing there? His fingers were straying about among the litter of tin tubes and dry brushes, seeking for something. Yes, it was for the long palette-knife, with its thin blade of lithe steel. He had found it at last. He was going to rip up the canvas.

With a stifled sob the lad leaped from the couch, and, rushing over to Hallward, tore the knife out of his hand, and flung it to the end of the studio. “Don’t, Basil, don’t!” he cried. “It would be murder!”

“I am glad you appreciate my work at last, Dorian,” said the painter, coldly, when he had recovered from his surprise. “I never thought you would.”

“Appreciate it? I am in love with it, Basil. It is part of myself. I feel that.”

“Well, as soon as you are dry, you shall be varnished, and framed, and sent home. Then you can do what you like with yourself.” And he walked across the room and rang the bell for tea. “You will have tea, of course, Dorian? And so will you, Harry? Or do you object to such simple pleasures?”

“I adore simple pleasures,” said Lord Henry. “They are the last refuge of the complex. But I don’t like scenes, except on the stage. What absurd fellows you are, both of you! I wonder who it was defined man as a rational animal. It was the most premature definition ever given. Man is many things, but he is not rational. I am glad he is not, after all: though I wish you chaps would not squabble over the picture. You had much better let me have it, Basil. This silly boy doesn’t really want it, and I really do.”

“If you let any one have it but me, Basil, I shall never forgive you!” cried Dorian Gray; “and I don’t allow people to call me a silly boy.”

“You know the picture is yours, Dorian. I gave it to you before it existed.”

“And you know you have been a little silly, Mr. Gray, and that you don’t really object to being reminded that you are extremely young.”

“I should have objected very strongly this morning, Lord Henry.”

“Ah! this morning! You have lived since then.”

There came a knock at the door, and the butler entered with a laden tea-tray and set it down upon a small Japanese table. There was a rattle of cups and saucers and the hissing of a fluted Georgian urn. Two globe-shaped china dishes were brought in by a page. Dorian Gray went over and poured out the tea. The two men sauntered languidly to the table, and examined what was under the covers.

“Let us go to the theatre to-night,” said Lord Henry. “There is sure to be something on, somewhere. I have promised to dine at White’s, but it is only with an old friend, so I can send him a wire to say that I am ill, or that I am prevented from coming in consequence of a subsequent engagement. I think that would be a rather nice excuse: it would have all the surprise of candour.”

“It is such a bore putting on one’s dress-clothes,” muttered Hallward. “And, when one has them on, they are so horrid.”

“Yes,” answered Lord Henry, dreamily, “the costume of the nine-teenth century is detestable. It is so sombre, so depressing. Sin is the only real colour-element left in modern life.”

“You really must not say things like that before Dorian, Harry.”

“Before which Dorian? The one who is pouring out tea for us, or the one in the picture?”

“Before either.”

“I should like to come to the theatre with you, Lord Henry,” said the lad.

“Then you shall come; and you will come too, Basil, won’t you?”

“I can’t, really. I would sooner not. I have a lot of work to do.”

“Well, then, you and I will go alone, Mr. Gray.”

“I should like that awfully.”

The painter bit his lip and walked over, cup in hand, to the picture. “I shall stay with the real Dorian,” he said, sadly.

“Is it the real Dorian?” cried the original of the portrait, strolling across to him. “Am I really like that?”

“Yes; you are just like that.”

“How wonderful, Basil!”

“At least you are like it in appearance. But it will never alter,” sighed Hallward. “That is something.”

“What a fuss people make about fidelity!” exclaimed Lord Henry. “Why, even in love it is purely a question for physiology. It has nothing to do with our own will. Young men want to be faithful, and are not; old men want to be faithless, and cannot: that is all one can say.”

“Don’t go to the theatre to-night, Dorian,” said Hallward. “Stop and dine with me.”

“I can’t, Basil.”

“Why?”

“Because I have promised Lord Henry Wotton to go with him.”

“He won’t like you the better for keeping your promises. He always breaks his own. I beg you not to go.”

Dorian Gray laughed and shook his head.

“I entreat you.”

The lad hesitated, and looked over at Lord Henry, who was watching them from the tea-table with an amused smile.

“I must go, Basil,” he answered.

“Very well,” said Hallward; and he went over and laid down his cup on the tray. “It is rather late, and, as you have to dress, you had better lose no time. Good-bye, Harry. Good-bye, Dorian. Come and see me soon. Come to-morrow.”

“Certainly.”

“You won’t forget?”

“No, of course not,” cried Dorian.

“And… Harry!”

“Yes, Basil?”

“Remember what I asked you, when we were in the garden this morning.”

“I have forgotten it.”

“I trust you.”

“I wish I could trust myself,” said Lord Henry, laughing. “Come, Mr. Gray, my hansom is outside, and I can drop you at your own place. Good-bye, Basil. It has been a most interesting afternoon.

As the door closed behind them, the painter flung himself down on a sofa, and a look of pain came into his face.

Adaptation

The Picture of Dorian Gray has been adapted into numerous films, stage productions, and even audio dramas over the years. Its most iconic adaptation may be the 1945 black-and-white film version, which garnered critical praise and earned Angela Lansbury an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actress.

More recent adaptations include the 2009 film Dorian Gray, which introduced the character to a modern audience, and the portrayal of Dorian in the TV series Penny Dreadful from 2014 to 2016.

The novel was also adapted for television by the playwright John Osborne in 1976. The BBC production starred Peter Firth as Dorian Gray, John Gielgud as Lord Henry Wotton, and Jeremy Brett as Basil Hallward.

Conclusion

The legacy of The Picture of Dorian Gray is one of profound complexity, both reflecting and challenging the societal norms of its time.

Initially reviled by Victorian society for its boldness in addressing topics of sin, morality, and forbidden desires, the novel has since transcended its early criticism to become a celebrated masterpiece. Oscar Wilde’s singular novel remains a compelling exploration of the human condition, particularly in how it examines the consequences of living a life in pursuit of beauty and pleasure without regard to moral consequence.

Its central themes resonate just as strongly today, reminding us that self-reflection, morality, and personal accountability are timeless concerns that transcend the ages.