Last updated on June 6th, 2024 at 11:31 pm

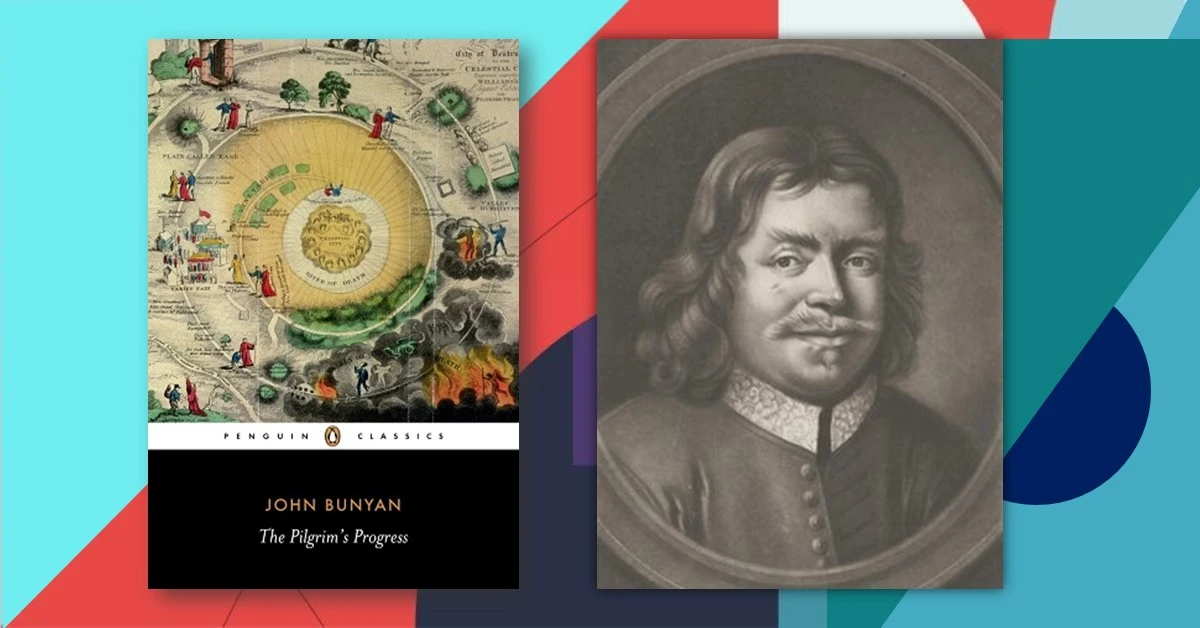

First published in 1678, The Pilgrim’s Progress is authored by John Bunyan, a Christian preacher, and portrays an allegorical journey of Christian his family from the City of Destruction toward the Celestial City.

It is an account of the struggle and obstacles he faces from people of different walks and faiths during his journey.

However, in his real-life John became a lay preacher when the English monarchy was restored to power in 1660, he was imprisoned in Bedford for unlicensed preaching. he was released in 1671 when Charles II all the penal rulings against Roman Catholics and Protestant nonconformists.

His most popular works were written during this period, along with The Pilgrim’s Progress which went through ten editions by 1985. Born in 1628 near Bradford, on August 31, 1688, John Bunyan died from a fever after having been caught in heavy rain on a ministerial visit.

The Pilgrim’s Progress Short Summary

In the 19th century, The Pilgrim’s Progress was a standard volume in nearly every cultured household in England. Most children read it along with the Bible and Shakespeare.

In the 20th century, its popularity declined, mainly due to changing views on religion. The Pilgrim’s Progress stands, for better or worse, as one of the monuments of Puritanism, a movement arising within the Church of England in the latter part of the 16th century, which sought to carry the reformation of that Church beyond the point represented by the Elizabethan settlement (1559). It is a part of our historical past rather than a dynamic influence in our present time.

However, The Pilgrim’s Progress has a good deal to offer the modern reader.

John Bunyan’s religious background may have been Puritan, but the doctrine that is at the heart of The Pilgrim’s Progress comes directly from the New Testament’s Sermon on the Mount where Christ teaches his followers to seek “first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness” and to avoid the broad path that leads to destruction.

In the book, Bunyan portrays a figurative account that presents in powerful and uncompromising terms, as to what it means to follow the narrow path to salvation of Christian, resisting all kinds of temptations and all worldly cravings and distractions along the way.

Stated in these terms, The Pilgrim’s Progress sounds grim; its message appears alien to modern times, I in fact, felt detached from the material world while I was reading it.

Still, if its doctrine is uncompromising, its characters and story are enlivened by Bunyan’s simple yet profound understanding of human nature. As Bunyan’s main character, Christian travels along the King’s highway, he encounters many different kinds of people. Some are pilgrims while others are absolute enemies of Christian, despising his devotion to a straight and narrow path.

Their emotional strengths and weaknesses are readily apparent to the modern reader, even if the characters are presented as allegorical figures rather than realistic, complex personalities.

The reader “hears” what they had to say, just as Bunyan undoubtedly heard them in the discussions he had engaged in as an unorthodox preacher. In the character of Christian, a reader may justly think that he is catching glimpses of Bunyan himself.

In The Pilgrim’s Progress, a modern reader can become familiar with the workings of a Puritan brilliant thinker. For Bunyan, the gospel of Christ was a living message that informed his every thought and action, and this complete commitment to the teachings of Christ is very much at the heart of Bunyan’s work.

However, The Pilgrim’s Progress need not be read-only for its Puritan elements, as its appeal is not primarily in its theology. Many critics see Christian as an Everyman figure whose quest represents any quest that begins in difficulty and ends in maturity, reconciliation, and death.

Christian’s journey is finally a journey that everyone makes in some way; it is one person’s way of confronting the essential difficulties and contradictions of human existence.

Background

The Pilgrim’s Progress is written in the “similitude of a dream”, like Saint John’s Revelation.

Bunyan recounts a dream in which he views the progress or journey of Christian (and later Christian’s wife Christiana) from the City of Destruction to the Celestial City.

Along the way, Christian passes by places bearing names such as Vanity, Beulah, Doubting Castle, and Beautiful. He also encounters physical difficulties like the Slough of Despond, the Hill Difficulty, the Valley of the Shadow of Death, and the river before the gate to the Celestial City.

Vis-à-vis the name, the background of The Pilgrim’s Progress consists of the places that represent different spiritual and mental states and temptations in regard to the fistful’s life. The Hill Difficulty may appear as a real hill to be climbed on Christian’s journey of faith; just as surely it represents the spiritual obstacles that must be overcome if Christian is to make progress on his journey to the Celestial City.

The caretaker of the Doubting Castle, Giant Despair, may appear to be a fairy tale monster who keeps his prisoners under lock and key. He also represents the particular psychological condition one will become a victim of when one’s faith begins to slip.

Elements of The Pilgrim’s Progress illuminate specific aspects of 17th-century life. One may read The Pilgrim’s Progress knowing nothing of 17th-century rural England, responding only to its vivid pictures and characters.

Places like the Valley of the Shadow of Death or the Delectable Mountains are physically described (as the valley is described as a narrow pathway between “a very deep ditch” and “a very dangerous mire”; the mountains comprise gardens, orchards, vineyards, and fountains), but the characteristics are so general that each reader may create his own image of them. Moreover, it is fascinating to see the popular illustrated editions of The Pilgrim’s Progress that have appeared in different languages across the world.

So wide is the demand of The Pilgrim’s Progress that artists recreate Bunyan’s famous scenes in a way that is fitting to their own time and culture.

When Christian and Faithful arrive at Vanity Fair, it could be any large commercial centre where people from different social classes and walks of life push with one another.

Here we have been the account that one will find for sale temptations and enticements that have been operating for five thousand years. However, when Faithful is apprehended and produced before the citizens of Vanity for placing his “principles of faith and holiness” before the prince, people, law, and practice, we find ourselves in the world of 17th-century England where religious differences were a cause of civil strife, and where a man like Bunyan could be imprisoned for long periods of time for unlicensed preaching.

Themes And Characters

The consisting characters of The Pilgrim’s Progress can be categorised into different suggestive categories.

The first category is the pilgrim. Christian is not the only character who is travelling to the Celestial City. Faithful and Hopeful also find a way to it, when in the second part, Christiana, Christian’s wife, is accompanied by her four sons and her maid Mercy. They ran into Feeble-mind, Valiant-for-truth, Despondency, Honest, and Stead-fast by the time they arrived at the gates of the Celestial City, all of whom were allowed to enter the city.

Going by their names, the characters of these pilgrims vary, and their ways of reaching to the Celestial City differ as well. Because, there are more than one way to the kingdom of God, and the human qualities needed for the journey toward it are not limited to one personality type.

Some obviously were opposed to the idea of pilgrimage and have set themselves on courses that keep them trapped in the affairs of this world. Characters bearing names like Obstinate, Atheist, Prejudice, and Ill-will are devoted to the earthly world. However, there is a third category of character: people whose errors are not as immediately obvious as those of the enemies of pilgrimage, but whose failings nonetheless condemn them to the abyss.

Maybe the grimmest character of The Pilgrim’s Progress is Ignorance, who reaches at the gate to the Celestial City only to be bound hand and foot and placed in a doorway to hell. In his preceding events, he seems possessed of an engaging goodwill, like Talkative, Pliable, and others.

Even though all these characters do not possess the necessary knowledge, understanding, or commitment to make a pilgrimage that demands a complete devotion to the teachings of Jesus Christ.

The uncompromising manner of Bunyan’s work can be the primary reason of losing popularity in this modern and pluralistic time.

Indeed, many critics see the damnation of Ignorance as an artistic flaw in Bunyan’s scheme. Not only is his punishment to Ignorance unkind in nature, it also seems a disappointment to end the work with the malediction of a relatively minor character rather than the triumphal entry of Christian into the Celestial City.

Other critics have come to the defence of Bunyan’s presentation of Ignorance, pointing out that Bunyan’s skill as a writer enables readers to see the poignancy of Ignorance’s situation. Bunyan does not condemn Ignorance; rather it is Ignorance’s own failure to fully come to grips with his human limitations that leads to his own damnation.

Additionally, to the characters who represent different human types, there are other two types of characters.

While the first type consists of monsters and giants, such as the “foul fiend” Apollyon, who is “clothed with scales like a fish” and has “wings like a dragon, feet like a bear”, “the mouth of a lion”, and smoke coming “out of his belly”, who would keep Christian from reaching his destination, the Celestial City, the second category consists of instructors who stand ready to help Christian and his wife on their journeys.

Nevertheless, it is the Evangelist who directs Christian in the direction of the Wicket Gate.

It takes Christian nearly half a day before he conquers this monster; he then proceeds with a drawn sword, ready for any enemy he might encounter.

As he walks towards his destination, the Celestial City, Christian encounters people like the three sisters Piety, Prudence, and Charity, who serve as religious guides. In the second part, Christiana is shielded from the worst temptations and snares that Christian passed through on his journey.

The inference is that most men need assistance and guidance. Christian is unusual in this regard as he makes the journey more or less on his own accord. In long sections he remains secluded from and alien to the rest of humanity, whereas Christiana always has people around her who think and act as she does.

Christian’s humbleness is balanced by his bravery and enterprise in setting out on his own journey; part of his petition to the general reader is the heroism inherent in his act of pilgrimage.

Literary Technic

The Pilgrim’s Progress looks backward to earlier traditions, while also prefiguring the work of later writers.

The specific backgrounds it exemplifies are those of the allegory and the Christian sermon. Placing allegorical action within a dream is a standard manoeuvre, since the Middle Ages.

The long tradition of giving sermons was a part of Bunyan’s experience, derived both from the popular sermon books and also his own, who is also a harbinger of later English novelists, like Daniel Defoe and Charles Dickens, in domestic humour, and caricature.

Bunyan’s allegorical characters live for the reader through the same emphasis on a single quality that established many of the humorous and eccentric characters of 18th- and 19th-century fiction.

Although there are elements of fairy tale and romance in The Pilgrim’s Progress, the heart of the work is the dialogues that Christian and Christiana engage in on their journeys. These dialogues provide a unique prose narrative technics the of Bunyan’s day. Most of the dialogues are aimed deliver a lesson.

The characters put each other’s religious doctrine and significance to common human experiences test.

Some dialogues are less obviously instructive.

Christian and his family may be ready for spiritual awakening, but others detest it. Many of the dialogues are discussions between the opponents and proponents of two distinct standpoints, who either are incapable of hearing what the other is proposing or simply discard it outright.

An event in which Christian involves in a debate between Formalist and Hypocrisy about the role of tradition in determining the validity of any practice can be mentioned here. Christian distrusts custom as a standard; Formalist and Hypocrisy argue that once something has been done for upwards of a thousand years it will be considered legal by any “impartial judge”.

The wisdom of their conflicting standpoints is then dramatically demonstrated as Formalist and Hypocrisy disappear into the byways of Danger and Destruction as Christian walks straight up the Hill Difficulty.

In an episode as such, all the literary qualities of The Pilgrim’s Progress converge together. The dialogue is easy and colloquial, in fact too much of it: the characters appear to be acquaintances or neighbours who differ on what is the most appropriate thing to do. Though the action is allegorical, what happens to them vividly illustrates the results of their particular beliefs and attitudes.

The overall effect of the episode is instructive: if we are believers, we apply the lesson of the episode to our own lives in the same way that we would respond to the message of a sermon.